Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

New York is the sixth most-touristed city in the world and by far the leading destination in the United States. Each year, tens of millions come to experience all that it has to offer, but very few come because of New York’s heritage in the American Revolution. Historical sightseeing is the fastest-growing part of an enormous tourism industry, and the Revolution is its leading edge, with millions of visitors to Revolutionary sites every year, but New York City is largely left out. As far as most of the nation is concerned, the Revolution happened in Boston and Philadelphia. New York has been branded a bystander in the events leading up to Independence, or, worse, chose the “wrong side,” and so has nothing to teach us about the story of the Founding. There is a different story to be told, however about NYC, the Revolutionary War, and America’s founding.

Uncover NYC’s Revolutionary War sites and little-known characters at the upcoming launch of the Gotham Center for New York City History’s NYC Revolutionary Trail! This talk will take place at the New York City Fire Museum tomorrow, June 6th.

Unlike Boston and Philadelphia, New York has no historic quarter. The Dutch and British homes of the colonial era burned down in a series of fires, and the city in general became the headquarters of economic development, clearing the way for an endless cycle of “creative destruction.” The city has never made a concerted effort to build up its historical tourism, with so many other far more profitable sectors. All these reasons, and others — not least, its displacement as the formal capital of the United States — caused the generations that followed to forget the central place that New York had in the events surrounding Independence.

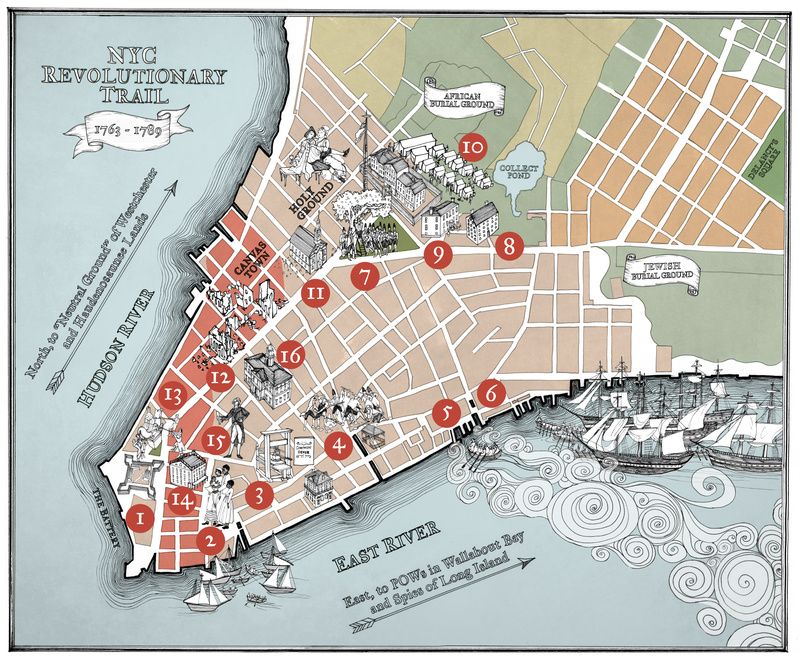

There are dozens of historic sites, in all five boroughs, which attest to New York’s outsized role in the period. Most remain unknown, even to residents, without the benefit of something like the Freedom Trail in Boston and Philadelphia, organizing them into a larger marketing association that constantly reminds visitors and locals of their city’s importance to the Founding. For that reason, The Gotham Center has created the NYC Revolutionary Trail, a website that provides a free multimedia walking tour of lower Manhattan, recounting the experience of the larger metropolitan area with the events of 1763-1789.

The 90-minute tour provides 75 minutes of guided audio narration, site information, select video, and character profiles at sixteen locations, each focusing on different themes, plus a “Library” online, which provides 40,000+ words of text and visual imagery, and extensive lesson plans for educators for grades 6-13. We are currently preparing to migrate this content onto a web-based smartphone app, that will offer far more interactive and immersive features, to digitally restore this vanished landscape, visualize some of the most dramatic events of the period, and generally fill this void in local and national memory, before the Revolution’s 250th anniversary begins in 2026.

New York, in truth, was the “City at the Heart of the American Revolution,” the key strategic objective for both armies. Its centrality extended to both the Imperial Crisis before the conflict and the Critical Period that followed it.

During the early 1700s, New York was just a small outpost in the British Empire, like most imperial ports. No more than a village really, it had less than 12,000 people and 1,000 houses, all within a couple of hours distance. But the city was radically transformed by a series of wars for control of early global trade, which allowed England to surge ahead of the leading imperial powers. Merchants on the southern tip of Manhattan provisioned the King’s army with clothes and weapons, while farmers in the larger metropolitan region provided food and drink — for tens of thousands. Ruling families like the DeLanceys and Livingstons became unimaginably wealthy, expanding into high-end businesses such as real estate, slavery, and privateering. Skilled tradesmen benefited enormously, too. As did free laborers, and everyone servicing the constant mill of sailors and soldiers. Over a few decades, New York doubled in population and quadrupled its built footprint, emerging as the unofficial capital of North America, the largest and fastest-growing part of Britain’s “first” empire.

With the French gone from the continent after their defeat in the Seven Years War in 1763 and the Spanish restricted to Florida, New Yorkers looked forward to enjoying the spoils, all the conquered land, and natural resources over the eastern mountain range. Most people in the city proudly identified as “Britons,” though few actually came from England. New York was unrivaled for its diversity even then. Most adult white men could vote, or purchase the “liberty,” unlike many in other ports – or England for that matter, to say nothing of the “absolutist,” or illiberal, Catholic monarchies.

There were some in London, however, most importantly the new prime minister George Grenville, who saw that North America would be increasingly hard to rule now that all the major imperial powers had been ousted from the giant landmass which was protected by two oceans. To pay for the astronomical debt that Parliament had racked up building its empire, and to kill any hopes that elites abroad might have for greater independence, London began tightly regulating the colonial economy. Subjects abroad were forbidden to print their own money, trade with rival nations, or take native land. Taxes on key exports, like sugar and molasses, were added, too.

Outside the ports, most people still lived as traditional farmers. Within the ports, nearly everyone was dependent on the mercantile system for labor and finance. Although small, cities were thus vital as the first to organize protests. New York was no exception. It was the leading consumer of British goods, and dependent by design: importing five times as much as it exported. After Parliament’s adoption of new taxes and economic rules, New York fell into a severe depression from which it never fully recovered. Trade on the East River, once teeming with hundreds of ships, carrying thousands of goods each month, came to a stop. Merchants saw their profits dwindle. Artisans fell into debt. Beggars filled the streets. The city’s huge maritime workforce, unemployed for the better part of the next decade, spent their nights at New York’s unrivaled number of taverns, growing increasingly mutinous and radical. These ordinary laborers spearheaded the revolt. Merchants in the Sons of Liberty were caught off-guard when they stepped outside their first meeting and saw thousands and thousands of the “Sons of Neptune” marching on Fort George, the enormous British garrison protecting (and policing) the colony, in what contemporaries dubbed the Great Riot.

The Liberty Boys would prove enormously influential over the next few years, spreading boycotts up and down the coast, inspiring other chapters around the region, and consistently pushing their counterparts to go further. They were most successful when the radicals among them, often nouveau riche sea captains, rallied the depressed maritime workforce. New York’s printers were also highly influential. Usually the first to receive news from England, which then circulated north via Boston and south via Philadelphia, they joined merchants in building previously nonexistent channels of intercolonial communication. New York hosted the first meeting of colonial leaders in 1765, the famous Stamp Act Congress. After dozens of protests, London rolled back the restrictive legislation, which taxed paper of all kinds (legal, business, media, etc.). In retaliation, however, Parliament enacted what one historian called the “greatest act of repression” until the blockade of Boston’s harbor. Parliament suspended New York’s legislature for years while enacting a new range of export taxes under the Townshend Acts.

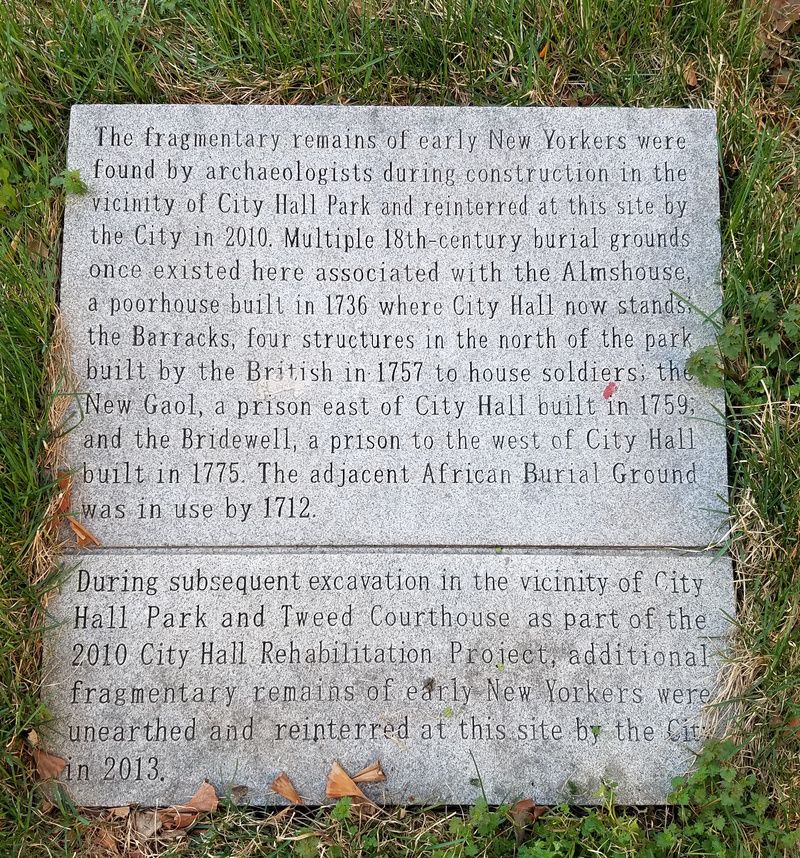

Nowhere was the reaction more explosive than in New York, which was forced to pay for the unrivaled number of soldiers placed in the city, the military headquarters of the British Empire in North America. Skirmishes and mobbed protests over the liberty poles that rebels hoisted on the Common, outside the main Barracks, exploded in the Battle of Golden Hill. This incredibly bloody two-day riot, known as the “first bloodshed in the Revolution,” was also the “fundamental catalyst” of a far better-known event, the Boston Massacre just a few weeks later.

The first wave of the Imperial Crisis had united virtually everyone, including the wealthiest merchants and the biggest landowners, nowhere wealthier or bigger than in New York. When a third wave of regulation followed a second partial repeal, Independence became the question of the day, and New Yorkers suddenly divided far more sharply and violently. Brooklyn, Staten Island, and Westchester were hotbeds of Loyalism. Queens and Long Island had greater numbers of undecided. Most of the city and the rest of the state supported rebellion. On that score, it was little different from the rest of North America, where historians now estimate that just 40 percent favored war, another 40 percent remained neutral, and 20 percent sided with the British.

In New York’s legislature, the upstate land barons in the “Livingston faction,” who the rebels had fiercely opposed until Golden Hill, became the inadvertent leaders of the revolt. The wealthy merchants in the “DeLancey faction,” their erstwhile allies, became loyalists. As so often in revolutions, the rebellion had taken on a life of its own. Radicals like Isaac Sears organized mobs that engaged in kidnappings, lootings, and vigilantism that alienated much of the public, and caused elites in both camps to panic. In this sense, New York very well represented what has become the dominant new concept for this period, the scholarship framing the Revolution as “the nation’s first civil war.”

The violence continued into the Occupation. After the rebels lost the city in 1776, New York became the military headquarters of the British again. Raiders on both sides and opportunistic bandits ravaged the wider metropolitan area, turning Westchester and Long Island especially into “semi-lawless no-man’s-lands.” Law and order did not return. The feature which made New York the center of military strategy for both sides at the start of the war — the city’s deep-water harbor at the mouth of a 144 mile-long river separating New England from the rest of the colonies — became far more of a liability than a benefit. The British could not police so vast a territory and population or meet the demands of fighting a counterinsurgency while also winning back the hearts and minds of civilians, in a war that rapidly depleted funds and natural resources and played havoc with supply-chain logistics.

New York served as the model for governance in every territory the British reconquered in all thirteen colonies. But it was the only city they managed to keep, and exhaustion with life on the home front and the experience of military dictatorship wore down even the neutral and the loyal. Over 20,000 flooded into New York, a third of all the Revolution’s battles taking place in the state. Another 20,000 slaves found refuge in the region, half the estimated number of runways in this “first emancipation.”

The war brought its usual evils: poverty, sickness, hunger, theft, corruption, and brutality. A fire, most likely staged by rebels, destroyed nearly a quarter of the city in 1776. Thousands lived under sailcloth in the charred ruins. The homelessness and overcrowding reached far beyond “Canvass Town,” as New York’s population bulged from 5,000 to 50,000 in just a few years. With two huge armies staged permanently outside the city, forests were leveled 12 miles in every direction, exacerbated by a record-cold winter that froze New York’s harbor solid. The cost of food jumped 800 percent. Talk of famine recurred. And epidemics of yellow fever, cholera, and smallpox took untold numbers. Each morning, cartmen wheeled the frozen, starved, pestilent dead. Some historians believe this experience was as important as the fighting itself, causing the British to eventually lose the neutral-loyal majority.

Just as disquieting perhaps were the infamous stories about the prisoner of war who died in New York, as many as 18,000, three or four times the number of rebel battlefield deaths. New York emerged from the war as the first US capital, the Founding’s main scene of action. The city became the first national media headquarters, circulating influential works like the Federalist during the close and equally divisive struggle over Ratification. The state’s anti-Federalist majority provided most of what became the Bill of Rights. But the Loyalists who remained may have been just as influential.

While a staggering 60,000 Loyalists fled the country, disembarking from New York in 1781-83, upwards of 450,000 stayed, one in every six members of the founding generation. They sided with the Federalists to enact a new, far more powerful government under the Constitution, after New York led the way — first in disenfranchising, then in reintegrating — this enormous population.

This story, and many others, were soon displaced from national memory. But there is every reason to put it back into the center of the narrative. The Revolution was an obvious foundational moment. And in New York, more than anywhere else, we find its complexity. For the Natives who controlled most of the western and northern part of the state, it was a preface to Indian Removal. The war divided the six Haudenosaunee nations of the “Iroquois” Confederation, arguably the most powerful Indigenous alliance on the continent. Both sides were targeted during the Revolution and eventually displaced, New York selling far more Native land than any other state.

It was a civil war for Blacks, too, who served crucial roles on both sides during the war, e.g., rescuing General Washington’s men from annihilation in 1776, or crippling rebel forces in various raids and campaigns. The “Loyalists” among them went on to found colonies in Novia Scotia and Sierra Leone. The “Patriots” stayed and helped jumpstart the world’s first antislavery movement. Many of the issues which propelled rebel farmers upstate continued, “land wars” flaring up into the mid-1800s over feudal-like concentration of property.

“Mechanics” in the city echoed many of the same complaints of the maritime workforce, helping to spearhead the abolition of property qualifications for voting a generation later. There are no shortages of legacies. And because New York served as the headquarters of the British during much of this period, it also forces us to examine the Revolution from the view of the “enemy,” not just the British generals and the ordinary Redcoat, but the neutral and the loyal colonials.

Most Americans probably think the story of the Founding is one they know. But in New York, it becomes far more diverse and complicated—fresh and interesting. You also start to realize that it is everywhere. I invite you to learn more about the NYC Revolutionary Trail. I promise you’ll never see the city the same way again.

Next, check out 11 Revolutionary War Sites in NYC

This article was written by Peter-Christian Aigner, Ph.D., Director of the Gotham Center for New York City History and Lead Creator of the NYC Revolutionary Trail.

Subscribe to our newsletter