Surprising Alternate Uses of NYC’s Ellis Island

Ellis Island is synonymous with immigration, but this island has served many purposes, from an FBI field office to a detention center!

For more than 60 years, from 1892 to 1954, the immigration station at Ellis Island processed millions of immigrants who traveled from all over the world to start a new life in America. Before immigration services were conducted on the island, the land played a significant role in the history of New York City, and when immigration stopped, the structures built on the island took on new roles. From acting as the base of a tavern to serving as a Coast Guard training station, Ellis Island has served many purposes through the centuries. Read on to find out more!

Hard Hat Tour of Ellis Island's Abandoned Hospital

Gain access to spaces usually off-limits to the public, with a Save Ellis Island docent!

1. An Oyster Bed Hot Spot

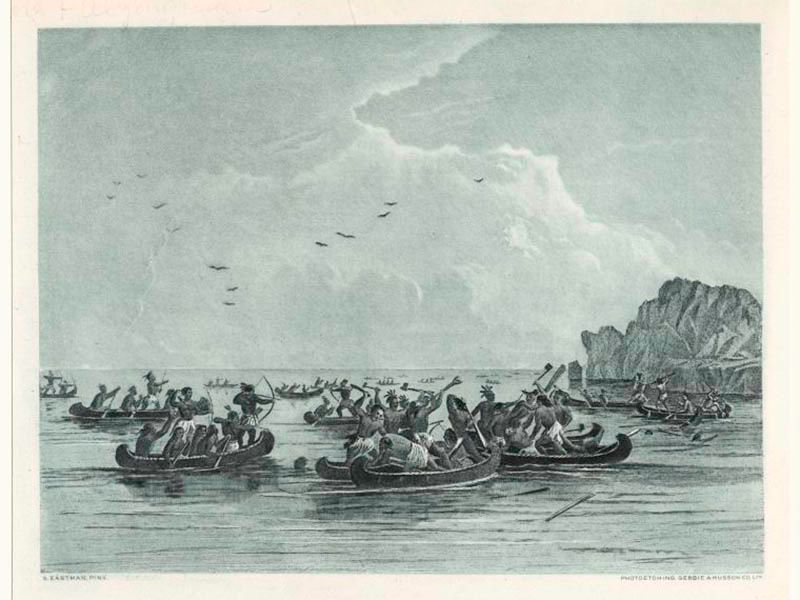

Before the European colonists came to America, Algonquin-speaking Native American tribes used Ellis Island as a home base to harvest food. The island contained large oyster beds and was also a spot where Native Americans could fish for clams and crabs and hunt for small animals. During restoration work on Ellis Island in 1985, archeologists found discarded shells, pottery fragments, and arrowheads, that gave an idea of how the Native Americans settled on and near the island. Fossilized plants, fish, duck, deer, and turtle bones painted a picture of the diet of the island’s original residents. When the Dutch colonists arrived and took over the island, they named it Little Oyster Island.

2. A Killing Ground for Notorious Pirates

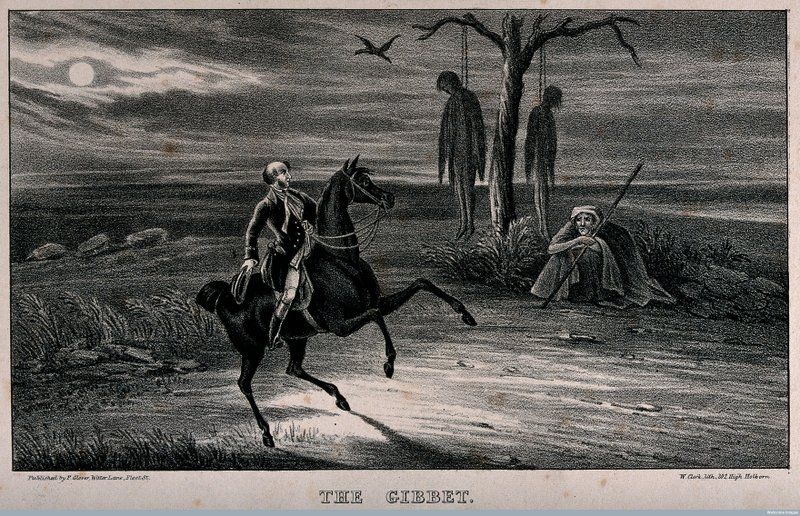

Under English colonial rule, Ellis Island — though it was not called that at the time — changed names various times depending on who owned it. In the late 1670s, Captain William Dyre, a customs collector who was granted the land by Sir Edmund Andros, the English colonial governor of New York, was the first English owner of the island. Over the next few years, the island went through many more hands, including Thomas and Patience Lloyd and New York State.

While the state owned the island, they referred to it as Bucking Island. However, this did not last for long. In the mid-1700s the notorious pirate Anderson was hanged on the island. Over the next several years more pirates were hanged on the island, and it earned the moniker Gibbet Island. Gibbet is another word for gallows. However, the legacy of the island’s first victim did not go unnoticed as the island was often referred to as “Anderson’s Island,” continuing the history of the infamous pirate.

3. A Fisherman’s Tavern and Oyster Bar

Samuel Ellis, a New York merchant, bought the island in 1774. Taking advantage of the bustling harbor around the island, Ellis built a tavern and oyster bar where sailors and fishermen could stop by to grab a meal, sip on a drink, and enjoy the views of the harbor. Ellis tried to sell “that pleasantly situated island,” in 1785, but couldn’t find any takers. He died in 1794 with the island still in his possession. Willing it to his unborn grandchild, the island would be passed on so long as that grandchild turned out to be a son and named after Samuel. Ellis’ daughter eventually gave birth to a son and named him Samuel after her father, but, sadly, the child died in infancy. In 1800, the State of New York took control of the island, along with Governor’s Island and Bedloe Island, which would later become Liberty Island. Despite this change of control, the Ellis family still maintained ownership of the island.

4. A Defensive Fort During the War of 1812

By 1808 the federal government obtained ownership of Ellis Island. They turned Liberty, Governor’s, and Ellis Island into a series of defensive forts along New York Harbor to protect the city from the British during the War of 1812. On Liberty Island, the government built a large fort named Fort Wood in 1807. The remnants of this fort make up the 11-point star that now serves as the base of the Statue of Liberty.

On Ellis Island, the government built a defensive fort between 1807 and 1811. They named it after Colonel James Gibson, an American soldier who died at Fort Erie. Fort Gibson served as a garrison and POW camp during the War of 1812. During the Civil War, Fort Gibson was equipped with twelve new cannons and 120 army and navy personnel. You can still see portions of the fort’s remnants on the north side of Ellis Island, near the American Immigrant Wall of Honor. Uncovered during excavations for the Wall of Honor, the exposed pieces make up about 25 percent of the complete fort.

5. An Ammunition Supply Depot

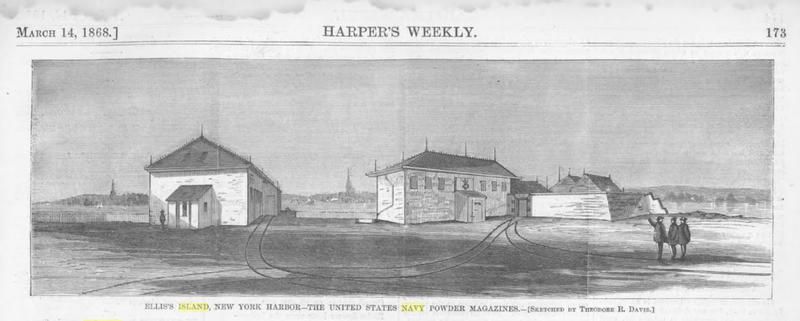

After the Civil War, the fort was decommissioned, and the army left the island — though the Navy continued to use the site as an ammunition supply depot. Barracks and officers’ quarters were converted into additional magazines and a tank house. New structures including a loaded shell house, powder house, steam fire engine house, kitchen, woodshed, carpenter shop, icehouse, and pigpen were built for the supply depot. The Navy built two new docks and additional railway lines between the main dock and the various magazines.

On the island, the Navy stored explosive black powder that was too unstable to store at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. This was alarming to residents of the city who were concerned about such explosive materials being stored so close to the populous city. An article in Harper’s Weekly in 1868 noted that Jersey City, Staten Island, Brooklyn, and New York were in “imminent peril of being at once destroyed.” It wouldn’t be until 1890 that Congress passed a resolution ordering the removal of the U.S. Navy’s powder magazine on Ellis Island. They moved the powder to Fort Wadsworth on Staten Island on May 24, 1890.

6. A World War I Navy Way Station

The first immigration station at Ellis Island opened in 1892. In that first year, the new immigration station processed over 400,000 immigrants. Immigration through Ellis Island would reach its peak in 1907 when 1.2 million people passed through the island in one year. However, when World War I began, there was a sharp decline in immigration. leaving room for the island to serve new purposes.

In 1916, a nearby explosion on Black Tom Island initiated by German saboteurs forced an evacuation of Ellis Island. When America entered the war in 1917, though, the immigration center turned into a Navy way station where ships could pick up supplies. The immigration hospital also admitted wounded servicemen. However, the island’s dark history as a space for detainment also began during this era when it detained over a thousand “alien enemies” who were people suspected of harboring pro-German sentiments.

7. A Coast Guard Training Station at Ellis Island

The passage of the National Origins Act, which required immigrants to obtain visas in American consulates at their country of origin before embarking for America, was a major factor that decreased immigration to the United States. However, with the advent of the Great Depression and the implementation of Country of Origin quota limits, immigration levels on Ellis Island steadily declined in the 1920s and 1930s.

With fewer immigrants to process, the island welcomed a new group to host: the Coast Guard. In 1939, the Coast Guard opened training stations at Ellis Island that served 60,000 enlisted men and 3,000 officers. The Coast Guard used the Baggage and Dormitory Building as their drill room, armory, boatsman storeroom, carpenter’s shop, and machine shop. The group used the New Immigration Building as dormitories where they would rest between their destroyer escorts and submarine chasers, among other tasks. The training station was decommissioned in 1946, but the Coast Guard returned to the Island in 1951 and established a Port Security Unit on the island when the U.S. Public Health Service closed the immigration hospital. The Coast Guard used the island’s recreation buildings and parts of the hospital complex for their offices. The FBI also had field offices in the hospital buildings.

8. A Detention and Deportation Center

Though the Coast Guard used many of the island’s facilities during World War II, the Main Immigration Building and hospital were also used by the military. Inside the Baggage Room, German merchant mariners seized at American ports were quartered until they could be transferred to inland detention camps. Additionally, nearly 1,000 United States citizens of Japanese, German, and Italian origin were detained on the island because the country considered them “alien enemies.” In addition to providing wounded detainees with hospital treatment, the military brought in members of the Daughters of the American Revolution to provide occupational therapy to detainees with lessons in needlecraft, sewing, and crocheting.

When the war ended, Ellis Island’s immigration processing functions returned to normal and those detained were either deported or allowed re-entry. The number of immigrants never again reached the peak of the early 19th century, and by 1949 the end of the island’s era of immigration services was near. The island was used as a detention center again during the Korean and Cold Wars in the early 1950s when the detainee population rose to 1,200 people. The island held New York residents without visas, seamen who deserted their ships, and stowaways on the island without bail.

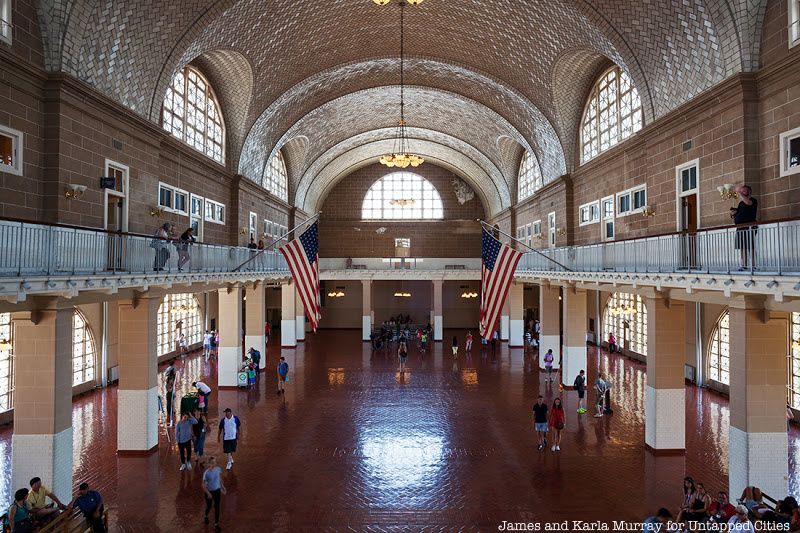

9. An Ellis Island Immigration Museum

After Ellis Island stopped offering Immigration and Naturalization Services in 1954, the government considered Ellis Island a federal surplus. Eleven years later, President Lyndon Johnson proclaimed Ellis Island to be part of the Statue of Liberty National Monument, giving control of the island to the National Park Service. However, the island fell into disrepair during this era of neglect and oblivion.

In the 1980s, the National Parks Service created a restoration project that aimed to restore the main immigration building to its appearance during the era of peak immigration between 1918 to 1924. These efforts allowed the Ellis Island Immigration Museum to open to the public in 1990. In 1999, the Park Service began to stabilize buildings in the hospital complex, which remains abandoned and off-limits to the public to this day except by guided tours led by Save Ellis Island docents. Save Ellis Island is a non-profit that was created to raise funds that support the restoration and re-use of the twenty-nine historic unrestored Ellis Island hospital buildings. The organization has already raised over $70 million and completed massive restoration projects including the restoration of marine corridors connecting the north side of the island to the south side, the magnificent Ferry Building, the Hospital Laundry Building, and an outdoor recreation pavilion. You can help support the Save Ellis Island mission by joining us on an upcoming hard hat tour of the abandoned hospital complex!

Hard Hat Tour of Ellis Island's Abandoned Hospital

Gain access to spaces usually off-limits to the public with a Save Ellis Island docent!

Next, find out if last names were really changed at Ellis Island?

Originally published in 2023.