Play Vintage Games at the Red Hook Pinball Museum

Explore the museum's collection of meticulously restored vintage machines from as early as the 1800s!

Discover Untapped New York’s favorite abandoned places in New York City’s five boroughs!

This list covers abandoned hospitals, islands, forts, mansions, and more fascinating urban places to discover. There are some great summer escapes like Fort Totten and Fort Tilden, as well as winter expeditions. While many of the listed locations are off-limits, others are publically accessible, like the abandoned hospitals on Ellis Island and remnants of the World’s Fair pavilions in Flushing Meadows-Corona Park, which you can visit by joining one of Untapped New York's walking tours!

North Brother Island, 22 acres off the coast of the South Bronx, has been abandoned for more than 50 years. Known as a former quarantine facility that housed infected patients — including Typhoid Mary — it is today in a state of decay. North Brother Island was shut down in 1963, though residents of the Bronx often headed to this area to party, something that has been cracked down on in recent years because of several dangerous incidents. Though the island is no longer occupied by humans, it is home to many bird populations and has been taken over by large amounts of vegetation. Check out our team’s previous exploration of North Brother Island here as well as the stunning images by photographer Christopher Payne.

The 101-acre Hart Island serves as the city’s last potter’s field, a. burial ground for the unclaimed dead or those whose families couldn’t afford a funeral. The island is uninhabited today, but more than 800,000 have been buried there since 1869, making it the largest tax-funded cemetery in the world. The history of Hart Island dates back to the mid-1800s, and reveals an intriguing past that extends far beyond the island’s current purpose as a public burial ground. Like North Brother Island and Rikers Island, Hart Island was often associated with society’s “unwanted.”

The strip of land was first used as a prison camp for Confederate soldiers during the Civil War. After the war, New York City purchased the island in 1869 and began using it as a cemetery; right after the first civilian burial of Louisa Van Slyke took place. From the time of the Civil War until World War II, other uses for the island included a prison workhouse for delinquent boys, a women’s insane asylum, an isolation zone during the yellow fever epidemic, an old men’s home, a tuberculosis hospital, and a reformatory. Today, most of the buildings on Hart Island have been demolished. See some of the last video footage of those historic structures here!

The now-barren subterranean space once served as a means to transport the Waldorf-Astoria's more famous guests discreetly, including supposedly General Pershing and Franklin Delano Roosevelt. It also supposedly served as an underground party space for Andy Warhol in 1965.

Today, the platform serves little purpose and is restricted to any passenger service and blocked from visitation. However, you can catch a glimpse of the site if you look to the right while leaving Grand Central. Like the secret subway station below City Hall, the Waldorf-Astoria’s underground platform is one of the many examples of New York City’s earlier subway systems whose designs are now deemed obsolete, but have entered the lore of the city’s abandoned places. The subway car pictured above has since been removed and transferred to the Danbury Railway Museum. We went out to visit the car and bust some myths about it, read our story here!

It’s been nearly fifty years since a freighter docked at the Red Hook Grain Terminal. Now black mold overspreads its concrete silos like a mourning veil. Its origins can be traced to the construction of the New York State Barge Canal in the early 20th century, which widened and rerouted the Erie Canal to facilitate the latest advances in shipping. But by 1918, New York City was lagging behind in the nation’s grain trade and the canal was failing, operating at only 10% of its capacity. This now-defunct facility was built in the Port of New York to invigorate the underused waterway—a state-run grain elevator in the bustling industrial waterfront of Red Hook, Brooklyn.

The collapse of the grain trade made up a small part of an overall decline along Red Hook’s industrial waterfront in the second half of the 20th century as shipping methods evolved and moved elsewhere. When the jobs dried up, much of the area cleared out, leaving a slew of vacant warehouses and decaying docks. In the year 2000, most of Red Hook’s 10,000 residents lived in the Red Hook Houses, one of the city’s first public housing projects. The development was a notorious hotbed for crack cocaine in the ’80s and early ’90s, but conditions have gradually improved over the years. A near complete lack of major subways and buses stalled gentrification in the neighborhood, but signs are becoming more common. Today, Van Brunt Street is scattered with specialty wine bars, cupcake shops, and craft breweries, and IKEA opened in 2007 on the site of a former graving dock.

The Grain Terminal has been the subject of a number of reuse proposals over the years, but none of the plans have amounted to real progress at the site. The building sits on the grounds of the Gowanus Industrial Park, which currently houses a container terminal and a bus depot, among other industrial tenants. Across from the Grain Terminal on Clinton Street, Samson Stages and Vanta Developers plan to build a studio and soundstage complex designed by Bjarke Ingels.

In Flushing Meadows-Corona Park, the oddball ruins of the “Tent of Tomorrow” are fading into yesterday. This land had been home to the Corona Ash Dumps—immortalized as the “valley of ashes” in The Great Gatsby—until master builder Robert Moses set out to transform the area by selecting it as the site of the 1939 New York World’s Fair.

Didn't make it to the 1939/40 or 1964/65 fairs? Here's your chance!

While the overall design of the park was laid out for the 1939 event, its most evident landmarks date back to the 1964 exhibition. The Space Age design of the New York Pavilion was intended to inspire visitors with the promise of the future, but today it serves to firmly plant the structure in the context of the 1960s. The New York State Pavilion was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2009, and a group of preservationists have helped clean up the exterior, restoring a bit of the original color scheme. The NYC Parks Department is in the process of completing the first major effort to preserve the Observation Towers and Tent of Tomorrow structures since the 1964 World’s Fair in Flushing Meadows Corona Park. The first phase finished in 2023 and was celebrated by lighting up the structures in NYC Parks green.

Decommissioned in 1945, this is a station unlike any other in New York, filled with stained glass, Roman brick, tiled vaults, arches and brass chandeliers. It was once the southern terminus of the Interborough Rapid Transit (IRT), which ran from City Hall to Grand Central, across 42nd Street to Times Square, and all the way north to 145th Street along Broadway. The design reflects the values of the City Beautiful architectural movement that believed beautiful architecture could engender a better civic society. The main consulting architects on the IRT stations were George Lewis Heins and Christopher Grant LaFarge. The glass skylights were made by R. Guastavino & Co.

Ride through the oldest stations, uncover hidden art, and more!

The curvature of the platform could not accommodate the longer trains we see today without extensive renovations, so the station was decommissioned in 1945 and is now one of the city’s most fascinating abandoned places. The station was designated an interior landmark in 1979. You can get a glimpse of the station by joining our tour of NYC’s underground subway where we’ll ride through it on the 6 train.

Seaview Hospital was once the largest tuberculosis sanatorium in the country. Now listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places, and is also a U.S. Historic District and New York City landmark. The historic district, which was developed next to the Staten Island Farm Colony, includes 37 buildings planned and developed between 1905 and 1938.

The NYC.gov website for the Sea View Hospital Rehabilitation Center & Home gives no indication of the surrounding abandonment, but indeed a few organizations have returned to operate from within the grounds, including a rehab center, volunteer firefighting organization, and volunteer ambulance service. The photographic team of 9/11 took a visit inside the crumbling remains of the Children’s Hospital at Seaview, as well as the underground tunnels beneath the main building, and shared with us their photos.

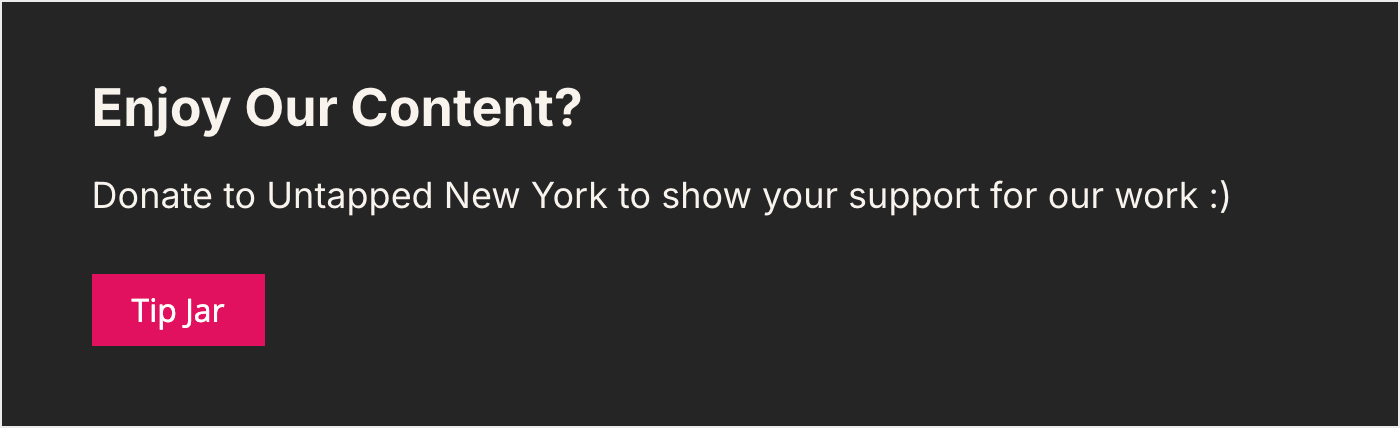

In 1877, the Long Island Rail Road opened a train line to the scenic Rockaway Beach. The line was successful for nearly a hundred years until the company that owned it went bankrupt in 1962. From that day on the rail line was left completely abandoned. Nature soon took over the structure and covered it with a layer of thick vines and weeds, making it a relic of its former self and obscuring the tracks from New Yorkers’ thoughts and sight.

In 2011, a group of activists developed a plan for the old rail line. Seeing the success of the High Line they decided to embrace the nature that had taken over the tracks and make it into the QueensWay, a park for joggers, bikers, and tourists. Untapped New York Members have gotten to hike a portion of the proposed trail!

Another competing group, the Queenslink has since been formed, seeking to reactivate it as a rail link (It should be noted that there have been several initiatives to study the reactivation of the Rockaway Beach Branch by the MTA and the Port Authority, but none so far have come to fruition, but perhaps that may change with renewed interest in transit line reactivations like the BQX, now the Interborough Express).

Just next to Floyd Bennett Field in Brooklyn, across from Fort Tilden and the Rockaways, sits Dead Horse Beach, which not only contains the remnants of dead horses but also a plethora of vintage garbage from over a hundred years ago. The landscape is dotted with bottles, among which you can find perfume bottles from the early 1900s, creepy toys, plenty of household knickknacks, decaying boats, and even (reportedly), old handguns. Millstone was also found there, leftover from the Dutch in the 17th century.

Dead Horse Beach functioned as the Brooklyn land dump from around 1850 to 1930 and was dotted with horse-rendering plants from the 1850s through the late 1910s. (Horse-rending is just a nicer-sounding term for what is done with dead horses, and you can still see pieces of horse bone on the beach.) Most of the plants burned down, but one remains amidst the tar. In August 2020, the National Park Service closed the beach area after the presence of radiological contamination was discovered.

Did you know that in 1930, 1,800 trolleys served Brooklyn alone? Although they date to 1936, their current resting place is the end-product of an attempt to create a trolley line between downtown Brooklyn and Red Hook in the ’80s and ’90s. Bob Diamond, founder of the Brooklyn Historic Railway Association (BHRA) spearheaded this movement, which was cut short abruptly when the Department of Transportation withdrew support. Trolley feasibility has been studied tangentially over the last 20 years as part of larger plans for Brooklyn Bridge Park and light rail service in the area, but so far nothing has come of it. While there used to be multiple trolley cars stored at this location, just one remains.

The Red Hook trolley car is just one of the unusual sites you can discover in the new edition of Secret Brooklyn!

The smallpox hospital was completed in 1856 and designed by James Renwick Jr. (who designed St. Patrick’s Cathedral). It was built using labor from the nearby lunatic asylum. It was open for 19 years and treated about 7,000 patients who had the “loathsome malady,” the nickname for smallpox. Many of these were impoverished immigrants who had not received the vaccine for smallpox yet or didn’t trust the immunization process or Union soldiers who needed curing.

Plans for the new hospital began in about 1850, as the Landmarks Preservation Commission reports when those afflicted with smallpox were cared for in “a pile of poor wooden outhouses on the banks of the river,” in the words of Resident Physician William Kelly. It admitted patients who could not pay, but also patients who could – making it a unique facility in New York City at the time. Up to 100 charity patients would be housed in the wards on the lower floors, with paying patients in private rooms upstairs. The hospital expanded in size over the years, with the north and south wings between 1903 and 1905.

In 1875, the hospital closed when it became too crowded and the facilities were relocated North Brother Island. The building was then used as a training hospital for nurses until 1950. It entered a period of abandonment and despair but was landmarked in 1976 by New York City. It remains New York City’s only landmarked ruin and one of its easy-to-reach abandoned places.

Located in Rossville, Staten Island, the Staten Island Boat Graveyard, also known as the Witte Marine Scrapyard, is New York City’s only remaining commercial marine salvage yard. The Witte Marine Scrapyard was founded in the 1930s by John J. Witte and is now the “official dumping ground” for decomposing vessels, in addition to decommissioned tugboats, ferries, and barges. Despite its desolate location, the “accidental marine museum” attracted many visitors. It is closed to the public and trespassing is forbidden.

Built in 1917, Fort Tilden has a history in almost all of America’s greatest wars. It served as a munition house during World War I, a force for defense in World War II, and even as a storage facility for nuclear weapons during the Cold War. Now, however, the fort has been left to nature, which has quickly taken it over.

Officially gifted to the National Park Service in the 1970s, the fort now remains a shell of its former self. Thick layers of green cover almost every inch of the base, but this isn’t necessarily a bad thing. The silos and amphitheaters have been used for art installations, performances, and even a Hurricane Sandy benefit. This place that was once a piece of war is now a part of nature and one of the city’s most popular abandoned places.

Hiding in plain sight, the abandoned South Side Hospitals on Ellis Island were one of the largest public health undertakings in U.S. history. While Ellis Island has become one of New York City’s top tourist attractions, drawing over two million visitors per year, the 22-building South Side hospital complex is hidden in plain sight, just to the left of disembarking passengers headed towards the Great Hall.

Gain access to spaces usually off-limits to the public!

After immigration restriction laws shut down Ellis Island as a port of entry, the complex was left to decay for nearly 60 years. Looking at its desolate, skeletal frame now, it’s difficult to imagine that it was once the standard for United States medical care and one of the largest public health undertakings in American history. See more photographs of the amazing buildings and crumbling interiors and join us for a tour of the abandoned Ellis Island hospital complex led by a Save Ellis Island docent.

The Westchester Avenue Station along Concrete Plant Park in the Bronx, which is just off the Whitlock Avenue stop on the 6 train, has now become overgrown with plants and vines. In its heyday, however, the Westchester Avenue Station was a transportation hub for those traveling on the New Haven Railroad, known as the NYW&B. Unfortunately, the NYW&B went bankrupt in 1937, stopping travel through this area.

The station, designed by Cass Gilbert, was an important work of Gothic architecture. Gilbert, also the designer of Lower Manhattan’s US Custom House and the Woolworth Building, was commissioned to build 13 stations, including Westchester Avenue, for the railroad in 1908. This station is among four from this commission that remain, along with Hunts Point Avenue, City Island and Morris Park, though all had fallen into disrepair by 2009. Local nonprofit groups are pushing to redevelop the station as a community space and entrance to a city park. In 2020, architecture firm SLO released renderings of what a renovated station may look like.

One of the oldest military installations in the country, Fort Wadsworth occupies 226 acres of Staten Island’s northeastern shore on the Narrows of New York Harbor. It was fortified by the British in 1779 and served as the prime defensive location throughout the rest of the Revolutionary War.

The original fort was demolished and reconstructed as Fort Richmond between the years 1847 and 1862. In 1865, three years following its construction, the structure was renamed Fort Wadsworth in honor of Brevet Major General James Wadsworth.

Although the structure was occupied in some capacity until 1995, it was mostly left unused and eventually fell into disrepair. That same year, it was turned over to the National Park Service’s Gateway National Recreation Area. While its third system forts (Battery Weed and Fort Tompkins) are well maintained and partially occupied by the Coast Guard, Army Reserve, and Park Police, other sections are abandoned places and remain off-limits to the public.

Fort Totten’s history stretches all the way back to before the formation of the United States. Originally inhabited by Matinecock Indians, the area was eventually settled by colonizers who dubbed the area Willet’s Point, during the American Revolution.

In 1864, the area was renamed for General Joseph Totten and fortifications began to make it a Civil War stronghold that would protect New York against the southern military. However, with the South’s increasing military ability, the fort soon became obsolete and was transformed into a makeshift military hospital. After the war, the military used the fort for a variety of different purposes until eventually abandoning it in 1974.

In 1987, the fort and the ten acres surrounding it were gifted to the New York Parks Department. Much of the area is used as a public space, featuring pools, sports complexes, and baseball fields, however, the NYPD and FDNY use the fort for training centers and it remains the base of operations for the Bayside Historical Society. Despite all the modern activity many of the old Civil War buildings still remain abandoned places and can only be accessed on guided tours with a Park Ranger, which our Untapped New York Members have gotten to experience multiple times!

Brooklyn’s Barren Island is home to Floyd Bennett Field, New York’s first municipal airport built in 1931. Sections of the site have been abandoned places since the Navy deactivated the airfield in 1971, but in its heyday, Floyd Bennett Field saw ascents by historic aviators, such as Amelia Earhart and Howard Hughes. With this kind of a storied history, the airfield naturally lends itself to having a few secrets.

The airfield was named after Floyd Bennett, a World War I aviator who was recruited to pilot an expedition to the North Pole. It has been the site of many historic flights, one of the most memorable being the outing by Howard Hughes in 1938 to circumnavigate the earth in record time. In 1941, the airfield shifted from a municipal airport to a Naval Air Station, where those who made and tested aircrafts worked during World War II. It soon became the busiest naval air station in the United States. The NYPD and FDNY have made use of the facilities post-war, mostly for storage. The site’s 1,300 acres of “grassland, saltmarshes, tidal mudflats, a marina, and the former airfield, including a control tower and terminal that is now the William Fitts Ryan Visitor Center (Ryan Visitor Center)” are run by the National Park Service.

Located underneath Riverside Park on the Upper West Side, the Freedom Tunnel is one of the city’s most frequented off-limits abandoned places. According to Will Ellis’ book Abandoned NYC, the Freedom Tunnel was first constructed as part of Robert Moses‘ Westside Improvement Project to address the problem of “Death Avenue,” a ground-level railroad track responsible for the deaths of several pedestrians. However, once the tunnel was completed, the rise of trucking made the track largely obsolete.

Many homeless people discovered the abandoned area by the mid-1970s, and a hundred resided there through the ’80s. However, in the 1990s Amtrak began laying new track, and many squatting there were forcibly removed by the NYPD in 1996. Today, the tunnels are remarkably clean, with the only signs of life from the graffiti on the walls. The graffiti of artist Chris Pape, nicknamed “Freedom” is the namesake for the tunnel. His graffiti recreated the works of Goya and Michelangelo and remained on the walls for several decades before Amtrak began to paint over it in 2009.

The Kingsbridge Armory on Kingsbridge Road in the Bronx was been vacant since 1995. The 575,000-square-foot building, once used to house the National Guard’s Eighth Coastal Artillery Regiment, has not been used for military purposes in more than 20 years. It has, however, been used for several other purposes, including the filming of the 2006 Will Smith film, I Am Legend, and an episode in the final season of The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel.

In 2013, Mayor Michael Bloomberg and the New York City Economic Development Corp. unveiled an initiative to transform the Kingsbridge Armory in the Bronx into the world’s largest indoor ice facility. However, that plan seems to have been scrapped. Curbed reported in 2021 that the armory might get transformed into a salsa museum, but as of the summer of 2023, the EDC is starting to run community engagement surveys and tours to collect feedback from the community on how to best make use of the facility.

The National Lighthouse Museum opened in 2015 and sits on part of the complex that was once a part of the U.S. Light-House Establishment. Even before then, however, the site was home to the former Marine Hospital, known as The Quarantine, where 1,500 of the city’s diseased were housed.

When the U.S. Light-House Establishment took over the space, it constructed new buildings to serve the U.S. Lighthouse Service’s Third District until the Lighthouse Service was folded into the United States Coast Guard in 1939. After the Coast Guard relocated to Governors Island in the 1960’s, the location was closed and was partially demolished and turned into the Staten Island ferry maintenance facility. Many buildings next to the museum, including the lamp shop, barracks, and the administration building are still standing, but remain abandoned.

Although part of the Creedmoor Psychiatric Center remains operational, a relic of its occasionally nasty past remains. Building 25 was once a center for the mentally ill, a part of the Brooklyn State Hospital, and one of the hundreds of Farm Colonies that were meant to house and rehabilitate patients. Rehabilitation was hardly what occurred, however. There are stories of abuse and neglect surrounding all of Building 25 and, in 1984, a patient was struck in the throat by a staff member and died, leading to the shutdown of the facility.

The building now lies vacant, a crumbling reminder of the facility that it used to house. The floors are still covered in toys and the walls, and the murals that cover them are peeling away. Perhaps strangest of all, however, is the pigeon infestation that has led Creedmoor to have one of the largest guano accumulations in the United States.

The Brooklyn Navy Yard Naval Hospital Annex (or the Naval Annex) was built from 1830 to 1836. It was active through the Civil War, supplying almost a third of the medicine distributed to Union soldiers, and both World Wars until it was decommissioned in the 1970s. Some of the first female nurses and medical students were employed there. Dr. E. R. Squibb, the leading pharmaceutics inventor and part-name sake of the pharmaceutics company Bristol-Myers Squibb, developed the first anesthetic ethers for use in surgery.

It’s one of the few original buildings that remain at the Navy Yard and one of the few abandoned places in this complex that’s being redeveloped. Steiner Studios, a major anchor tenant there, is working on transforming the space into a 420,000-square-foot media campus by 2027.

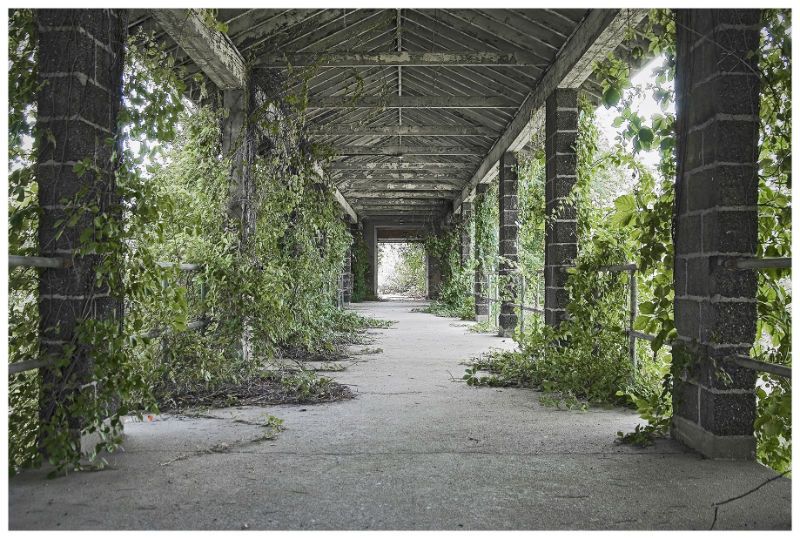

Located at 31 Canal Street, Loew’s Canal Theater on the Lower East Side was built in 1927 and, at the time of its construction, the theater was New York City’s second-largest theater, boasting 2,314 seats. Loew’s sold the theater to the Mayer & Schneider Circuit in 1929, though it quickly went bankrupt and was resold back to Loew’s within the year. The theater, designed by Thomas Lamb, was known for showing lesser-known films and serials. Though Loew’s Canal Theater closed in the 1950s, much of its decor remains in good shape. The facade of the building’s lobby has since been named a city landmark.

On the corner of West 167th Street lies an abandoned stone mansion building, with many windows and chimneys. However, it is inaccessible due to a chained door. The only peek into the building’s interior is through open windows which reveal that it has fallen into disrepair. The building, composed of multi-brick and stone, is surrounded by an apartment complex and smaller shops. According to Scouting NY, this mysterious building was once a parsonage for the Union Reformed Church in use from 1888 until 1925 when it was moved to its new location north of 168th Street.

Just off of Staten Island, between Newark Bay and the Kill Van Kull, sits Shooter’s Island, a former hunting preserve for wild geese during the colonial era. After the Revolutionary War, this 43-acre island became an industrialized site with a shipyard and oil refinery. The Townsend-Downey Shipbuilding Company constructed yachts on the island, including a racing yacht for Kaiser Wilheim II and the schooner yacht, Atlantic, which set the record for the fastest transatlantic passage by a monohull in 1905. Shooter’s Island then became a marine junkyard after World War I and was eventually abandoned by 1921. Now owned by the City of New York and maintained by the NYC Parks Department, the island remains one of NYC’s abandoned places to this day.

Deep in Ozone Park lies one of the largest burial grounds in New York, Bayside Cemetery. Covering 12 acres and housing over 35,000 burials, this Jewish cemetery dates all the way back to 1865. Used primarily as a burial place for cholera victims, Bayside has often found itself in disrepair, some even report claiming exposed human remains used to peak out of unmaintained graves. Still active today, the grounds have been restored and serve as the final resting place for Civil War vets and passengers of the Titanic but perhaps what the belt is best known for is the grave of Harry Houdini.

About 15 minutes away lies the Machpelah Cemetery. Abandoned in the late 1980s, the area has become a decrepit shell of its former self. Graves have succumbed to vandalism and the nearby offices have long since deteriorated. The only grave that remains pristine is that of Houdini’s. Some say there is a secret compartment somewhere in Houdinis tomb that when opened will reveal dark secrets, others say his spirit still haunts the area. Regardless of the truth, many Halloween nights, on the anniversary of the man’s death, mourners can be seen performing seances in hopes of speaking to his wandering soul.

Underneath Williamsburg at South 4th Street there’s a 6-track station of the IND line that was never opened. In 2009, over the course of a year, street artists PAC and Workhorse invited 100 street artists in and out of the station to create work there overnight. dubbed The Underbelly Project. The idea was to create an underground gallery, but as PAC describes, apart from recruiting artists they could trust from pre-existing relationships, everything “happened organically along the way.”

The project went on to be replicated in Paris. Whether the art still exists in the NYC subway station remains a question, but most we’ve spoken to feel that the MTA sealed off the station and it has remained relatively untouched. Second Avenue Sagas has a great explanation of the unused subway station.

The Chambers Street station has a long history of changes, with trains entering the station from the Williamsburg Bridge originally, then the Manhattan Bridge when it was completed. There was also a Rockaway Beach service that originated from Chamber Street from 1913 to 1917, operated by the Long Island Rail Road and Brooklyn Rapid Transit.

In 1931, the Nassau Street subway (now the J/Z lines) opened running south from Chambers Street. As part of this plan, two platforms were closed. Part of the station was converted into the basement of the Municipal Archives. Another platform was removed to accommodate the expansion of Brooklyn Bridge station.

The abandoned Bowery Station Platform was originally designed with four tracks and two island platforms. However today only two tracks at this station continue to be used, after renovations in 2004 removed one of the tracks and another remains inactive. One of the clearest signs that this platform is abandoned is that the space is completely devoid of benches. The Bowery Station Platform received some activity several years ago, as the spot was used by the NYPD to conduct terrorist drills, and a graffiti artist by the name of “VEW” created a Star Wars-themed Anti-ISIS graffiti mural.

Next, read about 20 of NYC’s Abandoned Subway Stations

Joyce Lam, Brennan Ortiz, Will Ellis, Erin Cabrey, and Jake Hanley also contributed reporting.

Subscribe to our newsletter