NYC’s Forgotten ‘War on Christmas Trees’

Discover how an obscure holiday crackdown affects festive street vendors today!

In 1940, P.A.B. Widener II opined that “the days of America’s privately owned treasure houses are over.” Writing in his autobiography, Without drums, Widener referred to his own family’s 110-room mansion, Lynnewood Hall, as “The Last American Versailles.” Prominent architect Horace Trumbauer designed Lynnewood Hall for Widener’s grandfather, Peter A.B. Widener. It was completed in 1899 in Elkins Park, Pennsylvania, a roughly 25-minute drive from Philadelphia. The formerly abandoned estate is a favorite spot among urban explorers who have been drawn to its empty and decaying grandeur and tragic stories of the family who live there. The home has long been “shrouded in mystery and shrouded in controversy,” said Angie VanScyoc, Chief Operations Officer of the Lynnewood Hall Preservation Foundation – but no longer.

Untapped New York made a visit to Lynnewood Hall to explore its many rooms and uncover a few of its secrets. We spoke extensively with VanScyoc and the Foundation’s Executive Director Edward Thome about the building’s history, its hidden gems, and the ambitious plans for its future. “There is such a rich history here, not just of the era of the Gilded Age and the family that lived here, but also of tradesmen, craftsmen, architecture…Think of all the stories that could be told,” VanScyoc mused. “It has an uncanny way of drawing you in and not letting you go,” said Thome, who has been mesmerized by the building since he was just 11 years old. While there are fascinating stories to be found around every corner of the massive building, we’ve picked out a few of our favorites to expand upon here. Read on to learn more about this stunning estate (and see photos from inside), from its tragic ties to the Titanic to its hidden room full of safes, mysterious tunnel system, and how you can visit!

The original owner of Lynnewood Hall, Peter A.B. Widener, died with a personal fortune that would have been worth tens of billions of dollars today and a museum-worthy art collection, but he came from humble beginnings. Born to a butcher in West Philadelphia, Widener also went into the meat business. His first big break in business was winning a contract to supply mutton to Union troops during the Civil War. He used his earnings to invest in street car lines and moved his way up the political ladder in Philadelphia until he became City Treasurer. He had holdings in foundational American companies such as U.S. Steel, American Tobacco Company, and Standard Oil. Though Widener was one of the wealthiest Americans to ever live, his money couldn’t insulate him from tragedy.

After his wife, Hannah Josephine Dunton, died in 1896, Widener realized he wanted to keep his family close. He commissioned architect Horace Trumbauer to build a home large enough to house the families of Widener’s two sons, George and Joseph, and his own expensive art collection. “Lynnewood is the home that art built,” VanScyoc said, noting how important the art collection was to the family. Widener began collecting art around 1885 and by the time Lynnewood was complete in 1899, he had amassed a collection of priceless masterpieces that included paintings by Raphael, Rembrandt, Vermeer, Gainsborough, and more. The collecting bug was passed on to his son, Joseph, who expanded on his father’s collection.

Widener arranged his works of art in five different galleries throughout his home, one on the first floor and four on the second floor. Each gallery was designed to display specific works based on the artist and style. To ensure the safety of his prized collection and to show the pieces in the best (literal) light, Widener had his home built with the latest technology. “Even though the building is a classical piece of architecture, it’s very technologically advanced,” VanScyoc said.

The main gallery, for instance, is surrounded by walls of concrete 2 feet thick as a fire precaution. The galleries on the second floor were lit by diffused skylights. Above the skylights, there is a mechanical system of long fins that can be adjusted to direct sunlight as the sun changes position in the sky throughout the day. The gallery skylight is also rigged to a ventilation system that allows a person to turn one wheel and simultaneously open a series of glass panels to let air flow.

The art galleries were named after Widener’s favorite artists, including Rembrandt, Raphael, Cellini, and van Dyck. Within each, paintings were displayed on red velvet walls, the remnants of which you can see hanging throughout the galleries today. In the Cellini room, niches in the walls housed precious jewelry items crafted by the Italian goldsmith Benvenuto Cellini. The Rembrandt Room held all Rembrandts. The van Dyck room, which is VanScyoc’s favorite, was also Widener’s favorite. It once held a portrait of Widener by John Singer Sargent. “Restoration would make these galleries the preeminent galleries in the country,” said Thome.

During the Depression, the Wideners opened their art galleries to the public so that anyone who wanted to could see the treaures inside. The philanthropically minded Joseph Widener bequeathed the family’s art collection, over 2,000 items, to the National Gallery in D.C. where you can see many of the items on display today. That creative and philanthropic spirit will be carried on in the estate’s future.

While working to clean up the mansion and learn more about it, the Preservation Foundation has made many surprising discoveries. One such hidden gem they’ve found is a room full of individually locked safes. It is tucked away behind the Butler’s Pantry and squeezed between the first and second floors and is the only room in the mansion that doesn’t appear on floor plans. There are fourteen safes in total, each lined with a dark blue velvet. These safes likely held the finest pieces of silver from the Widener’s dinner service. Unfortunately, no long-forgotten treasures were found inside when they were opened.

The Lynnewood Hall Estate didn’t just include the 100,000-square-foot mansion and the nearly 35 acres of land it sits on today. It originally covered 300 acres. On that land were two structures that still exist – Lynnewood Lodge (the former stables) and the Gatehouse – as well as a lost farm, a Normandy-style village for the staff, a powerplant, greenhouses, a polo field, and more. Snaking below the property is a large system of underground tunnels. VanScyoc told Untapped New York that the tunnel system may be even larger than they know. One branch of the tunnel system definitely goes from the basement of the main house to the central fountain in the front yard. A few manhole covers have been found around the property, but there may be more to uncover.

Another fun fact about the land is that the original gardens were buried. Upon the death of Peter Widener, his son Joseph inherited the property. Joseph and his father had slightly different tastes when it came to architecture and landscape design. Peter’s original landscaping for Lynnewood Hall was of an Italianate style with sunken gardens lined by balustrades. After Peter died, the sunken gardens were filled in and topped with a formal French garden.

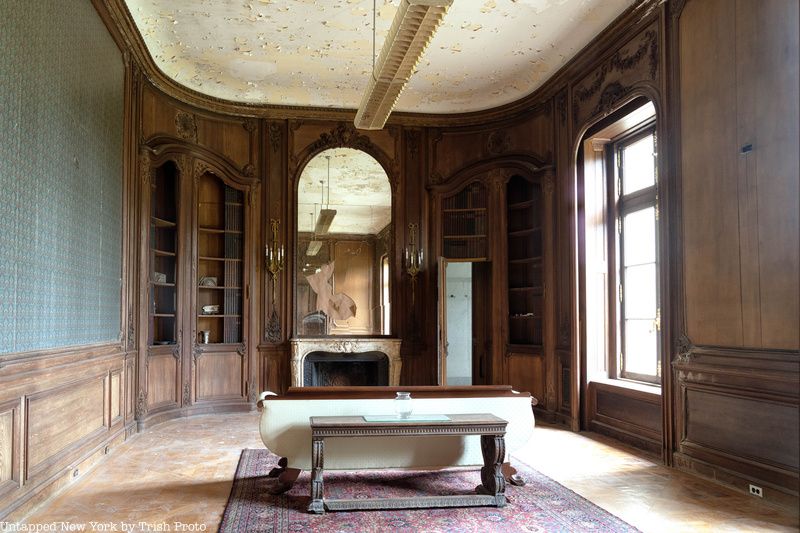

The smoking room is full of secrets! Take a peek at the right-hand side of the photo above. In the bookcase to the right of the mirror, you can see a hidden door. The door leads to a marble-clad bathroom for the gentlemen who would have enjoyed lounging in this space. The right side of that bookcase actually hides more shelves behind it, complete with false book spines. Throughout Lynnewood Hall there are many hidden doors, usually disguised as mirrors. Some doors are also fake. Rather than opening, they are simply built against a wall and give the illusion of an entryway.

The couch in the smoking room is called the Abraham Lincoln couch because, so the story goes, Lincoln once sat in it. The couch, which is not original to the home, is allegedly from the New York Governor’s mansion and was graced by Lincoln’s rear end when he came to visit.

Many wealthy 19th-century families, the Wideners were touched by the tragedy of the Titanic. The family of Peter’s eldest son, George, booked tickets on the Titanic for their return trip from Paris. George and his wife Eleanor owned the Philadelphia Ritz-Carlton, so they were traveling to Europe to find a new chef for the hotel. They also needed to pick up a wedding trousseau for their daughter Josephine and some rare books for their son Harry. Harry, George’s valet Edwin Keeping, and Eleanor’s ladies maid Amalia Geigerhey went along for the trip. When the Titanic sank, George, Harry, and Edwin sadly lost their lives. Eleanor and Amalia made it safely to New York. This tragedy has long been one of the things that Lynnewood is most known for, but there is much more to the story of the Wideners and their opulent home.

The ballroom of Lynnewood Hall is perhaps the grandest space in the home. Decorated in a Louis XIV style, it’s covered with walnut paneling that is adorned with ornate gold leaf details. And just look at that ceiling! The central mural that hangs above is believed to be from the 17th century and comes from an Italian villa. This room hosted extravagant balls in the time of both Peter’s and his son Joseph’s residency. However, before the raucous costume balls and performances by the Philadelphia Philharmonic Orchestra, this room was much quieter.

It was originally a library. The walls were covered in velvet and there were built-in bookshelves at the four corners of the room. It was converted into a ballroom around 1912. The blocked-off entryway you see in the photo above used to lead out into the conservatory. If you were to walk from there to the second conservatory on the opposite end of the home, you would cover 268 feet, one of the longest residential enfilades in the country.

There were roughly 40 live-in staff members at Lynnewood during the Widener’s time. They slept on the upper floors of the home above the galleries where there were more than 20 bedrooms. They worked down in the basement where you would find the kitchen, bakeries (one for pastries and one for bread), wine cellar, carpentry shop, upholstery shop, coal storage, and more workspaces. Among these spaces though there was once an area reserved for the family, a private bowling alley. When more staff came on and additional housing was needed, the bowling alley was converted into bedrooms, workspaces, and a billiards room for the staff. In the basement today visitors will notice a fireplace mantelpiece that seems quite ornate for servants’ quarters. This was once part of the bowling alley room.

The only freestanding piece of furniture that is original to the home and still in the home is the organ bench pictured above. After Peter Widener died, the estate went to his only surviving son Joseph. Joseph lived there until his own death in 1943. At that time, the estate was liquidated in an auction covered by outlets like the New York Times and Life magazine. Everything that hadn’t already been donated to the National Gallery in D.C. went to the auction block. The auction drew hundreds of eager bidders and lasted five days. According to Life, the most expensive item purchased was a “tapestry-covered sofa and eight matching chairs that had once belonged to Louis XV.” It sold for $30,000.

It took a while for the hall to find a new owner after the Wideners. “It was a completely different time,” Thome notes, echoing the writings of Widener’s grandson, “People couldn’t keep up these types of homes anymore.” In 1952, a buyer finally came through. The estate was purchased by Faith Theological Seminary, a Christian school led by Carl McIntire. When the Seminary needed funds, it would sell off parts of the mansion, like wood paneling or mantelpieces. This trend would sadly continue with the next owner who came in 1996, Dr. Richard Yoon, leader of the First Korean Church of New York. Over the ensuing decades, Lynnewood Hall started to come apart piece by piece. Now, the Preservatin Society is working to restore the home to its former glory.

The Grand Hall at Lynnewood makes a statement. With soaring ceilings over 40 feet high, intricate carvings, and a wide central staircase, it was an entrance befitting the grandeur of the exterior. While the classical exterior design of the home was inspired by Prior Park in Bath, England, this room was inspired by the entryway at The Breakers, the Newport Estate of Cornelius Vanderbilt II. Comparing photos of the two entryways, you can see the similarities. They are both ringed with arched entryways topped by marble accents. There is a central staircase emerging from one of these arched portals in both homes. The Corinthian pilasters are nearly identical and details on the coffered ceiling and moldings are strikingly similar.

What sets these two spaces apart is the floor. Lynnewood Hall has a checkered black and white floor while the floor at The Breakers is all white, but Lynnewood’s floor was also originally all white as well. When Joseph Widener made renovations to the home around 1915, he added the checkered pattern. It was a popular element in French chateaus. Joseph sprinkled many elements of French influence throughout the mansion.

There is a very long road ahead before Lynnewood Hall can be open to the public. However, there is a way you can get inside while simultaneously supporting the Foundation’s preservation efforts. You can do this by joining a Pre-Restoration Hard Hat Tour. Money from these tours will go toward covering the $1,250,000 cost of asbestos remediation. The tours will be scheduled for after remediation is complete in approximately 4 to 5 months.

The Lynnewood Hall Preservation Foundation was formed in 2019 and officially took ownership of the estate on June 30, 2023. In the years leading up to the purchase, board members worked closely with the previous owner to install security cameras on the property, make essential repairs like fixing broken windows and stopping leaks, and start clean-up efforts. The Foundation is currently waiting on the final report from a conditions assessment which will lay out the roadmap for the estate’s restoration journey. “It’s a daunting project,” VanScyoc admitted, “but from our perspective, we always had the faith that it could be.”

Thome explained that the ultimate goal of the restoration of Lynnewood Hall is to make it a cultural center and art museum. “For me,” Thome explained, “the goal is seeing the original intention of the house at its creation be honored by filling the art galleries with fine art again.” But that’s not all the Foundation seeks to do. Preserving the home is about more than just bringing back the old glamour of the Gilded Age. There will also be opportunities for education throughout the restoration process. VanScyoc sees opportunities for those interested in building arts to learn skills from expert craftspeople while helping to restore the property. “It’s not just about the stewardship of the house, but also saving the house so that everyone can appreciate it.”

“In a world that is constantly seeking to divide us,” VanScyoc told Untapped New York, “when you come inside this house, you can step into this door and be part of something bigger than yourself. Whatever might inspire you may be different from what inspires 50 other people, but in it we can all find something we’re struck by together.”

You can find ways to support the Preservation Foundation’s mission here and donate directly at this link. Stay up to date on news from the estate on Instagram and Facebook.

Next, check out 10 Gilded Age Mansions You Can Visit

Subscribe to our newsletter