How to Make a Subway Map with John Tauranac

Hear from an author and map designer who has been creating maps of the NYC subway, officially and unofficially, for over forty years!

The West Village is one of New York City’s most recognizable and dynamic neighborhoods. Located within Greenwich Village, the West Village typically extends from Christopher Street up to West 14th Street. Known for its decades-old brownstones, narrow but quaint streets, and historic properties that redefined the artist and LGBTQ+ community of New York and abroad. With an odd street grid and its historically bohemian culture, the West Village has plenty of secrets to uncover. Here is part one of the top 20 secrets of the West Village!

Tenth and Eleventh Avenues that extended throughout the West Village were known as Death Avenue in the 19th century for good reason. By the 1840s, the area featured three-story Greek Revival rowhouses, the homes of merchants who would open shops on the ground floor. By mid-century, the Hudson River Rail Road constructed freight train tracks up 10th Avenue at street level with no barriers to protect pedestrians and cars from the trains. It was estimated well over 500 people died and nearly 1,600 were injured on Death Avenue from around 1850 to 1910.

In an attempt to solve this growing problem, a city ordinance created the West Side Cowboys who rode alongside the train tracks waving a red flag or red lantern to warn drivers and pedestrians of oncoming trains. Until 1941, these cowboys would ride down 10th Avenue escorting freight cars. Even though the trains often were as slow as six miles per hour, injuries still continued, making it necessary for the cowboys to continue working to save pedestrians. The last stretch of tracks was removed in 1941 after about a decade of removal efforts.

Weehawken Street is one of the quieter streets of the West Village with some properties that date back nearly 200 years ago. The one-block street takes its name from the ferry landing that connected the area to Weehawken, New Jersey, across the Hudson River. The land around what would become Weehawken Street was Newgate State Prison, opened in the late 1790s. The prison was actually somewhat of a tourist attraction due to its high stone walls, though its poor conditions led it to close in favor of Sing Sing Prison further upstate. Nearly four decades later, after the prison closed, a produce market was built on Weehawken Street, ultimately becoming the short-lived Greenwich Market that closed a decade later.

As the decades progressed, the buildings served as everything from stables to boarding houses to saloons. However, 6 Weehawken Street dates back to the original wooden Market House from the 1830s. All buildings on Weehawken Street are now part of a historic district of 14 buildings that trace their history back to maritime industrialization. 7 Weehawken Street is another historic property in the district, built for carpenter Jacob P. Roome and later purchased by Cornelius Van Schaack Roosevelt, the father of Theodore Roosevelt.

The Westbeth Artists Community is a storied complex providing living and working space for artists, though five decades ago, the building had a very different purpose. The 13-building complex was originally part of the Bell Laboratories Building at 463 West Street and was the site of major scientific breakthroughs from 1898 to 1966. Such innovations include black-and-white and color television, the phonograph record, radar, and vacuum tubes. Additionally, some research for the Manhattan Project was conducted at the site, and the first baseball game was broadcast through Bell.

After Bell Labs moved, the building was converted into the Westbeth Artists Community, creating live-work spaces for 384 artists who met certain income requirements. The building was renovated to include rehearsal studios, commercial spaces, and performance halls. Early artists who resided there included photographer Diane Arbus, artist Hans Haacke, and Vin Diesel. Cultural organizations including The New School for Drama, the Martha Graham Center of Contemporary Dance, and LAByrinth Theater Company also moved into the space.

Cherry Lane Theatre is New York City’s oldest continuously running off-Broadway theater, data back to its first performance in 1924. The building, though, dates back over a century prior. It originally served as a farm silo, as well as a brewery and box factory. In 1923, a group of authors, most notably Edna St. Vincent Millay, opened the Cherry Lane Theatre, with regular performances of new releases and plays dating back to the 17th century starting as soon as the following February. Eugene O’Neill, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Gertrude Stein, and W.H. Auden all had plays produced at the theater in its early years.

By the 1950s, the theater was due for a makeover, and it acquired many items from the Center Theatre of Rockefeller Center in 1954. With the interior remodeled, the theater put on particularly avant-garde and absurdist productions, including a play written by Pablo Picasso. Samuel Beckett had a number of premieres at the theater, as did Sam Shepard. The theater also put on the Mentor Project, pairing Pulitzer-winning and Pulitzer-nominated playwrights with aspiring authors.

The High Line, one of Manhattan’s most frequented spots, used to be around 50% longer than it is today, running through the West Village down to St. John’s Terminal in Tribeca. The High Line today, however, only stops at Gansevoort Street in the Meatpacking District. The High Line was originally built for trains to travel above ground following multiple deaths along 10th Avenue from locomotive accidents. Trains went back and forth on the over two-mile route, distributing all sorts of goods from refrigerated meats to Oreo cookies along the west side of Manhattan.

However, by the 1950s, the High Line was not as necessary with the rise of container shipping ports along the New Jersey side of the Hudson River, rendering the lower third of the High Line unnecessary. As more buildings were constructed, major sections of the High Line were taken down, including the section that would become the Jacob K. Javits Center. Though most sections were destroyed, two still remain, both of which actually went through buildings: the Westbeth Artists Residence and the West Coast Apartments. Both of these sites show some semblance of what was formerly the route.

West 4th Street crosses West 10th, 11th, 12th, and 13th Streets, one of the stranger geographical oddities in New York City. Manhattan’s grid system, which is mostly regular near New York University, becomes much more confusing in the West Village, with its twisting block-long streets and its own confusing grid that tilts almost perpendicular to the rest of Manhattan’s grid. For instance, between West 10th and West 11th Streets are Charles Street and Perry Street, while West 11th and West 12th Streets are separated by Bank Street and Bethune Street. For the most part, the streets in the West Village are not numbered but rather have the familiar names of, for instance, Christopher Street or Waverly Place.

West 4th Street passes along the southern edge of Washington Square Park (where it is known as Washington Square South), then travels west to 6th Avenue, where instead of going straight, it turns northwest. Then, it curves even more north after crossing 7th Avenue, where it then travels almost directly north up until just west of Jackson Square, one of the city’s oldest parks. The square is actually a triangle, as it is trisected by Greenwich Avenue, 8th Avenue, and Horatio Street. West 13th Street also technically bypasses the park, as it continues west toward the Meatpacking District.

The Whitney Museum today is a $422 million building designed by Renzo Piano in the West Village, spanning eight stories (two of which are devoted to the museum’s permanent collection). Though the building opened in 2015, the Whitney Museum was originally founded in 1930 by Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, a great-granddaughter of Cornelius Vanderbilt. Whitney was also the oldest daughter of Cornelius Vanderbilt II, who founded the New York Central Railroad, built Grand Central Terminal, and owned a French chateau mansion on Fifth Avenue and 57th Street. On West 8th Street in the Greenwich Village, Whitney had a carriage house that functioned as her studio, designed in 1918 by American artist Robert Winthrop Chanler.

Whitney collected art as early as 1905, and after failing to donate hundreds of paintings to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Whitney decided to open her own American art museum in 1929. The museum ultimately moved to a structure on 54th Street behind the Museum of Modern Art, though a fire at the MoMA in 1958 led the Whitney to move again to 945 Madison Avenue nearly a decade later. Until 2018, the Whitney was at the Breuer Building, featuring a granite stone staircase façade. The Whitney also operated a small branch at 55 Water Street from 1973 to 1983, as well as hosted satellite museums across the city. The museum failed multiple times to expand in the Upper East Side due to costs and design failures.

At 360 West 11th Street in the West Village there is a residential building that was constructed in the style of a Venetian palazzo. Called Palazzo Chupi, the building was designed by artist and filmmaker Julian Schnabel and constructed atop a former horse stable that was converted into a stable. The name comes from a Spanish lollipop brand called Chupa Chups, and the palazzo was painted a bright pink. The building dates back to around 1915 and also served as a perfume studio.

The building stands at 12 stories, and construction was very fast to beat potential height limitations. The building includes a large terrace with Italian-inspired arches, and parts of the building resemble Padua’s Scrovegni Chapel. Madonna, Johnny Depp, and Richard Gere all lived in the building, the first four floors of which are Schnabel’s. The palazzo has been met with mixed critical reviews; while some have considered the building an authentic representation of Italian architecture, others including Andrew Berman of the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation called it “woefully out of context and a monument to this guy’s ego.”

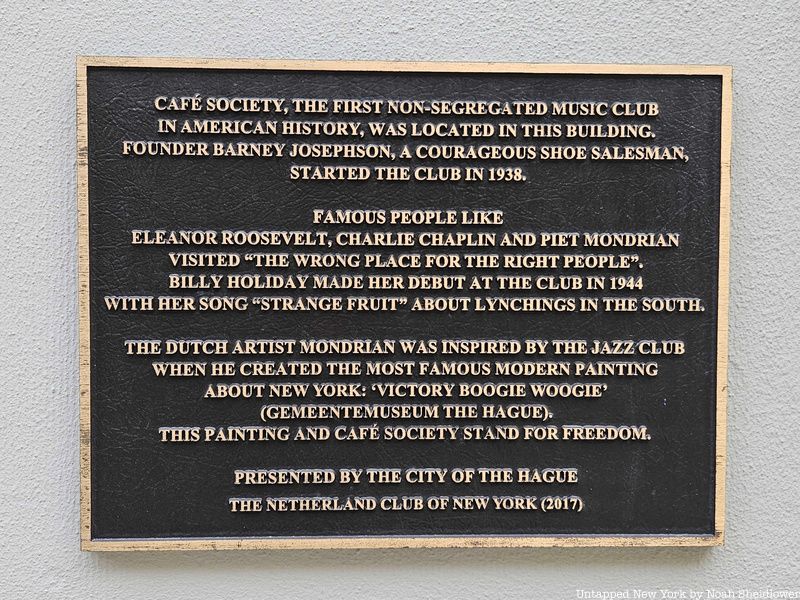

Though it was only open for a decade, Cafe Society played an important role in integrating musicians of all races. Cafe Society was a West Village nightclub that operated from 1938 to 1948, created by Barney Josephson. Josephson founded the club at first to highlight African American artists, featuring a premiere of Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit.” Josephson cited how the Cotton Club, one of Harlem’s top jazz clubs, limited Black visitors to just the back third of the establishment. Josephson had no experience with nightclubs but envisioned an integrated environment for both musicians and customers.

He stated, “I wanted a club where Blacks and whites worked together behind the footlights and sat together out front… There wasn’t, so far as I know, a place like it in New York or in the whole country.” He decided to open the club in the West Village, a predominantly white neighborhood, and advertised it as “The Wrong Place for the Right People.” The club treated Black and white customers as equally as possible given the political climate, and it helped launch the careers of Lena Horne and Ruth Brown. The club, as part of efforts to further integrate other music venues, raised money for left-wing causes.

The West Village (and Greenwich Village more broadly) puts on the world’s largest Halloween parade, commonly called the Village Halloween Parade. The parade is going into its 50th year, having been founded in 1973 by puppeteer Ralph Lee. The parade, which now attracts over two million spectators and around 50,000 participants, started as a small puppet parade around the Westbeth Artists Community. The parade expanded to around 200 participants in 1974 when the parade went from Jane Street to Washington Square Park. It seemed with each year, the number of participants grew exponentially, as more nonprofits and theater organizations helped expand it. The LGBTQ+ community in the West Village was also instrumental in the parade’s growth.

The official route now runs on Sixth Avenue from Spring Street to 16th Street, though for years, Westbeth was the starting point and Washington Square Park was the endpoint. Buildings like the Jefferson Market Library starting in the 1970s installed a giant spider, while a devil sat on the Washington Square Arch. As the routes changed and thousands more spectators joined each year, the parades began being broadcast, including just a few weeks after 9/11. Over the last two decades, some puppets and carnival figures were designed in support of fundraising efforts and social causes, such as funds to help the Haiti earthquake victims in 2010. In recent iterations, the parade has attracted over 50 marching bands, parade floats, and elaborate costumes.

Next, check out the Top 10 Secrets of the Whitney Museum!

Subscribe to our newsletter