Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

On this Indigenous Peoples’ Day, let’s take a moment to honor the Native populations that still live in the five boroughs as well as those who established villages 400 years ago where many skyscrapers stand today. According to the latest census from 2021, 180,866 (about 2 percent) of New York City’s population identifies as either fully or partially “American Indian or Alaska Native.”

Today, many sites across the city take their name from Lenape words, such as Gowanus and Canarsie, but there are few markers of the Lenape’s history in New York. Organizations like the Redhawk Native American Arts Council and New York Indian Council work to preserve diverse Native American cultures in the city; however, most New Yorkers likely do not know about the significant indigenous peoples’ history that shaped the development of modern New York.

Here is our guide to the Native American heritage sites across the city, including museums and organizations devoted to documenting these stories and neighborhoods where Native Americans once lived before European settlement.

The National Museum of the American Indian in New York, also called the George Gustav Heye Center, features exhibits by and about Native Americans. Heye was a collector of Native American artifacts who opened the museum in 1922 in a building at 155th Street and Broadway. Although the museum ultimately relocated to Washington, D.C., a branch of the museum moved to the Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House on Bowling Green. The Beaux-Arts building now houses a permanent collection called “Infinity of Nations” with over 700 items. The museum features Tiffany woodwork in the Collector’s Office, an entranceway ceiling meant to resemble leather and a Guastavino rotunda with a 140-ton skylight.

Currently, the museum’s exhibitions include: “Why We Serve: Native Americans in the United States Armed Forces,” “Stretching the Canvas: Eight Decades of Native American Painting,” and the “Infinity of Nations” collection. The permanent collection features a Kayapó krok-krok-ti, a macaw-and-heron-feather ceremonial headdress; an Apsáalooke (Crow) robe illustrated with warriors’ exploits; a Mapuche kultrung, or hand drum, depicting the cosmos; and a Chumash basket decorated with a Spanish-coin motif. Over 30 painters have their works on display, including Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Kay WalkingStick, and Jeffrey Gibson. In 2022, the museum will showcase the art of Yanktonai Dakota artist Oscar Howe and Tlingit glass artist Preston Singletary.

The American Indian Community House (AICH) aims to improve and promote the well-being of the American Indian Community in New York City and to increase the visibility of American Indian cultures in an urban setting. The AICH community comprises Native Americans from 72 different tribes and is located on Eldridge Street. The AICH was founded in 1969 by Native American volunteers and has for over five decades worked to foster intercultural understanding.

The Two-Spirit Indigenous People Association (TSIPA) was created as a task force to organize two-spirit community events for NYC’s historic WorldPride 2019. The AICH has been involved in protecting the city’s thriving two-spirit community, which consists of Native peoples who fulfill a traditional third-gender role in their cultures. The AICH also launched the Healthy Elders Network, which supports those living and aging with HIV. The organization also puts on frequent arts and community events.

Bowling Green was a significant cultural site for Native American groups before European colonization. Modern-day State Street corresponded to Kapsee, meaning “sharp rock place,” which was a notable spot for the local Canarsee Lenape even though nobody lived there due to its rockiness. It is believed there was a Kapsee chief hut at the foot of the Wickquasgeck Trail, which would later become Broadway.

The Wickquasgeck trail, which was the first north-south trading route in what is now New York City, went from today’s Bowling Green all the way up to Montreal. At the foot of the trail was a large elm that would have denoted a sacred spot where council fires were held. It is clear that during the Lenape era, lower Broadway was a significant government and commercial site. Easy access to Manhattan’s waterfront would have been particularly important for collecting resources, and direct access to the harbor would have given Native Americans increased protection.

Although little is known about the Native Americans living around Bowling Green, there was a documented massacre that took place there in 1643. William Kieft, the governor of New Netherland (whose capital was New Amsterdam), ordered European soldiers to attack two camps of Lenape refugees, who had fled raiding Mahicans. They lived in huts in what is today the Lower East Side and had previously lived among the Dutch colonists in Fort Amsterdam. The massacre came about following conflicts between Natives and colonists, and about 30 people were killed around Bowling Green.

Inwood Hill Park, the northernmost point on Manhattan island, was a significant Lenape area that still has some artifacts from the 17th century. Over four centuries ago, the Lenape used the park’s caves as seasonal living quarters, and they would fish and harvest shellfish from nearby waterways. Old campfires, pottery, tools, and weapons were discovered in the park, likely from when the Lenape fled Mohawk attackers.

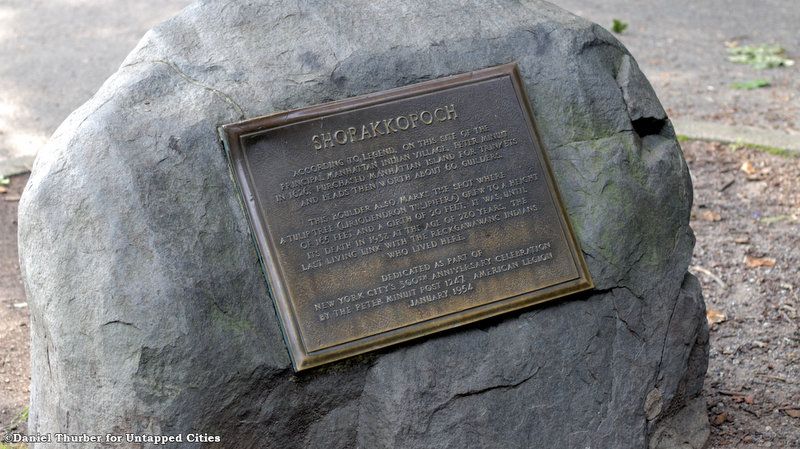

According to legend, in 1626, Peter Minuit, the Director-General of New Netherland, “purchased” Manhattan from the Lenape in exchange for a shipment of goods. The sale may have occurred under a tulip tree at the park, which grew for 280 years before its death in 1938. Today, the iconic site is marked by a plaque on the Shorakkapoch Rock, a large boulder on the far side of a large open field.

The earliest settlement in Greenwich Village was named Sappokanican, a village of the Lenape. It was located on the shores of a trout stream referred to as Minetta Brook. Dutch settlement began in the area starting in 1629. Wouter van Twiller, the third director of New Netherland, began a tobacco plantation near the village, which was so successful that some believe the word “Sappokanican” may have meant “wild tobacco.”

The village served as a trading settlement and docking point, but as Dutch farms pushed further north, the Lenape attacked farms, burned crops, and killed a handful of settlers. As a solution to this, William Kieft, who oversaw the transportation of African slaves to the area, granted some of them freedom and parcels of land, which physically separated the Dutch from the Lenape. There are few traces of these Native American populations in Greenwich Village today. It is likely that Native Americans stopped living in the area once the British arrived in 1664.

Astor Place was a large Lenape gathering space called “Kintecoying,” where Manhattan’s three major Lenape groups came together. In the 16th century, the Canarsie, Sapohannikan, and Manhattan met at “Kintecoying,” which meant “Crossroads of Three Nations.” There was likely a large oak or elm tree at the meeting spot, under which leaders would discuss political issues, trade with one another, and play games. Although the groups spoke different languages, they would often play baggattaway, now known as lacrosse. John Jacob Astor, the area’s namesake, gained a fortune trading furs with the Lenape.

In addition to being the location of Kintecoying, Astor Place was also where Red Cloud, chief of the largest tribe of the Teton Sioux Nation, gave a speech at a reception in his honor at Cooper Union. “We want preserves in our reserves. We want honest men, and we want you to help to keep us in the lands that belong to us so that we may not be prey to those who are viciously disposed,” he said at the end of his speech.

Near Astor Place on Second Avenue between about 10th and 14th Streets was the village of Shempoes. The trail from the village went from where St. Marks Church sits today to Astor Place through 9th Street and St. Marks Place.

Foley Square in Lower Manhattan’s Civic Center was the location of Werpoes Village, a settlement on the banks of the Collect Pond. The pond was the main city water supply system for the first two centuries of European settlement. The Munsee lived by the pond until Dutch settlement, and to the west of the pond was Kalck Hoek, where many oyster shell middens were left.

Werpoes was the southernmost village on the Wequaesgeek Road. Archaeologists posit that the residents of this village may have sold the island to European settlers in 1626, not those living at the northern tip of modern-day Manhattan. Werpoes was known for its fertile land on which crops grew easily.

Pearl Street in Lower Manhattan was considered the Lenape shell heap, since at the time it was the eastern shoreline of the island. The Lenape would leave seashells in the area after likely eating the meat inside. About half of the world’s oysters around that time lived in New York Harbor, and one would definitely believe it given that these shells were piled several feet high. Pearl Street was eventually even paved with oyster shells.

A bit further north, also along the coastline, was Rechtanck Village, situated near Clinton and Montgomery Streets along the East River. Rechtanck was located by a freshwater pond and brook. Unfortunately, like the residents of modern-day Bowling Green, those in Rechtanck were also massacred by Kieft’s forces. Rechtanck was also located near Cherry Street, which is where the Lenape had their cherry orchard. Along Cherry Street, New York Edison Company found buried dugout canoes, likely from the time of the Lenape.

On Governors Island was a village called Paggank, or Nut Island, which was named for the area’s abundance of hickory, oak, and chestnut tree nuts. The island, which was used seasonally, was ample for fishing and agriculture for local tribes. The village spoke Canarsee, but there is little evidence that there were any permanent settlements on the island.

Exactly 100 years after Giovanni da Verrazzano first observed the village’s residents in 1524, the first settlers in New Netherland settled on what the Dutch called Noten Eylandt. Wouter van Twiller commandeered the island for his personal use, and he drew up a deed with two Lenape leaders so he could cultivate a farm on the island.

Minetta Lane and Minetta Street in Manhattan are named after Minetta Creek, which was one of the longest waterways in Manhattan. The Lenape named the creek “Manetta,” which means “evil spirit” or “snake water.” The creek was known for its abundance of fish, including pike, bass, and pickerel. Manetta may refer to an evil snake from mythology that was conquered, leaving just the creek behind.

A swamp near where Washington Square Park sits today was fed by the creek. Around the time the Lenape inhabited the land, the location served as a gathering spot, as well as a marketplace and public play area.

In East Harlem, the Lenape may have used the area for hunting wild game including deer. The Wecksquaesgeek Indians were a Munsee-speaking band of Wappinger people who inhabited Harlem near the Hudson River. The Wappinger were closely related to the Lenape and Mahicans. They also called the Harlem River “Muscoota,” in reference to the grassy plants that grew alongside the waterway.

To the southeast of Morningside Heights were the settlements of Rechewanis and Konaande Kongh in present-day Central Park. A bit south of West Harlem on today’s Upper West Side, many Lenape gathered at modern-day Park Avenue and 98th Street at Konaanderkongh, a camp for hunting.

The shores of today’s Pelham Bay Park in the Bronx were where the Siwanoy would gather for sacred ceremonies. Translated as “southern people,” the Siwanoy resided in small camps and fished in the surrounding bays. In addition to serving as burial grounds, the shore was a source of wampum, cylindrical beads often made from shells strung together and worn as decoration or used for money. It is believed that the northwestern shore of Hunter Island and the entrance to the Kazimiroff Nature Trail were significant ritual sites. At Pell’s Point, now known as Rodman’s Neck, the Siwanoy established a marketplace.

When the Dutch first arrived, trade with the Siwanoy was quite prosperous, but the Dutch established settlements on Siwanoy land, which led to conflict. Eventually, after years of conflict and disease, the Siwanoy sold the land to Englishman Thomas Pell at the Treaty Oak. A new oak that marks the signing of the treaty is protected by an iron gate. Before fleeing the Bronx to upstate New York or Connecticut due to hostile conditions, one of the Siwanoy chiefs who signed the treaty, Ann-Hoock, may have killed Anne Hutchinson.

In around the 14th or 15th century, the Wiechquaskeck, a Munsee-speaking band of Wappinger people, settled in the forests of Van Cortlandt Park. They formed the village of Keskeskick (Mosholu), which relied on the nearby Spuyten Duyvil Creek and Hudson River. In 1646, Dutch settler Adriaen van der Donck purchased the land and paid chief Tacharew, and his house was built on present-day Van Cortlandt Lake. Van der Donck’s wife and other Dutch settlers were forced to flee to Manhattan from the Bronx in the Peach Tree War, a large attack by several tribes including the Susquehannock along the Hudson River.

Today, the park includes Indian Field, which honors Chief Abraham Ninham and the 17 Mohican Indians who died here when aiding the Americans in the Revolutionary War. The Mohicans tracked the British as they traveled through the Bronx and reported their advances to the revolutionaries. While following the British in Van Cortlandt Park East, the British discovered them and forced them into the woods, where they were later killed.

In the Bronx along the East River were several Native American communities largely forgotten today. In Hunts Point was Quinnahung, The old Hunt burial ground was located by a spring, while at the tip of the point was an important meeting point. Around Soundview Avenue and Leland Avenue was the village of Snakapins, which had about 60 lodges. There was likely a planting ground further south, and located around Clason Point were numerous fishing stations. In Castle Hill was a Native settlement whose name was not recorded that contained a large shell-heap for making wampum beads.

Perhaps near modern Ferry Point Park was a notable burial ground where Native populations would bring the dead from further inland. Shells and scattered objects were uncovered and signaled that burial rituals occurred at the site. Possible summer fishing spots were found in Locust Point, while at Weir Creek in Throgs Neck, the Siwanoy likely settled after encounters with settlers.

The residential neighborhood of Canarsie in southeast Brooklyn takes its name from the Canarsee peoples, a band of Munsee-speaking Lenape. The Canarsee are credited with selling Manhattan to the Dutch, but they likely lived at the intersection of Seaview and Ramsen Avenues in this area of Brooklyn around Jamaica Bay. Canarsee cornfields were centered around East 92nd Street, and shell heaps were found as late as 1930.

Canarsee leaders such as Penhawitz signed three land agreements with Dutch settlers between 1636 and 1667. By the time most of their land was sold to the Dutch, only three Native families still lived there. But the Canarsee also constructed Red Hook Lane, which passed through the marshland and connected Red Hook with Brooklyn Heights.

The northwestern Brooklyn neighborhood of Gowanus takes its name from a Canarsee chief named Gauwane. The site was settled in 1635 by the Dutch, but the Canarsee had inhabited much of the coastline in the era prior. Gowanus, though, had a small but thriving Native population as late as the 1960s.

In 1916, Mohawk Native American ironworkers made their way to New York to work on the construction of the Hell Gate Bridge. By the 1930s, a Mohawk community of over 800 people lived in what was then known as North Gowanus, or Boerum Hill. The community earned the nickname “Downtown Kahnawake,” named for the reservation near Montreal. The Wigwam Bar at 75 Nevis Street was a Mohawk community hub in the neighborhood.

The Lenape who lived in Coney Island referred to it as Narrioch, perhaps meaning “land without shadows.” A Native American tribe called the Konoh is said to have inhabited the land, which might have inspired Coney Island’s current name. Henry Hudson anchored his ship in Gravesend Bay in 1609 and began trading with the local Canarsee population, who subsequently attacked his party the next day. The Canarsee used the marshes of Coney Island for making money, but they went back to trading with Hudson due to potential economic gains they could secure. They also used the beach to collect wampum and clams.

The Dutch allowed a group of English dissenters to occupy the land, but the Konoh attacked the home of the English leader Lady Moody. However, Lady Moody negotiated with them for grazing rights in the marshes. On May 7, 1654, a Native named Guttaquoh declared himself the owner of “Coyne Island.” However, this attempt was unsuccessful, since the local population was completely wiped out in 1655 by the rival Mohawk Indians for not paying tribute to the Five Nations.

The Canarsee who lived in modern-day Bay Ridge were referred to as the Nyack, whose name means “point of land.” The Nyack built a settlement along the shores of Bay Ridge and traded with the Dutch. Reports from 1645 note how Cornelis van Werckhoven, on behalf of the Dutch West India Company, gave the Nyack six coats, six kettles, six axes, six chisels, six small looking glasses, twelve knives, and twelve combs for a portion of land nearby.

In Greenpoint, the Mespeatches used the land as hunting grounds. The area was too swampy for habitation, but those who interacted with the local settlers at first traded with them before inevitable conflict.

Native Americans also had settlements in Bushwick, Gravesend, and Fort Hamilton, which they called Navack. Sheepshead Bay had been used as a source of wampum, and there were villages established by the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Brooklyn Heights was also referred to as Ihpetonga, or “high sandy bank.”

The area that is now Maspeth in Queens was home to the Mespeatches tribe, one of the 13 main tribes that inhabited the Long Island region. They set up a village just east of what is now Mount Zion Cemetery. The area had plenty of swamps, which led to their name meaning “at the bad water place.”

The Dutch settled the area in 1642, but conflicts with the local tribes led them to move to Elmhurst and Manhattan. The Maspeth tribe also lived along Flushing Bay, and there was a trail that roughly corresponds to modern-day Grand and Flushing Avenues.

In the Rockaways, the East River Culture created pottery around 1100 A.D., and they are likely the ancestors of the Algonquian-speaking tribes. In the early 1600s, the Recouwacky tribe created villages in the area and built a dome-shaped wigwam. In 1645, the tribe signed a peace treaty with Dutch governor Willem Kieft. Tackapausha was elected sachem of tribes under the Dutch jurisdiction: the Massapequas, the Merikokes, Canarsees, Secatogues, Rockaways and Mattinicocks. The name Rockaway may derive from “Reckonwacky,” meaning “the place of our own people,” or “Reckanawahaha,” meaning “the place of laughing waters.”

The Old Rockaway Trail corresponds roughly to Jamaica Avenue, passing through the neighborhoods of Woodhaven, Richmond Hill, Jamaica, Hollis, and Bellerose. Jamaica probably comes from a word for “place of the beaver,” in reference to the many beavers in waterways north of Jamaica Bay. Native Americans who lived in the Jamaica area may have interacted with the Matinecock of the Kissena Park region, with “Kissena” meaning “cold place.” The nearby Olde Towne of Flushing Burial Ground also contains the remains of many figures of Native descent.

Ward’s Point, the southernmost point of both Staten Island and New York state, contains an archaeological site inside Conference House Park often considered one of the best preserved sites for studying Native American history in the state. Evidence of Paleo-Indian presence dates all the way back to around 6,000 BC. The burial ground, which remains unmarked, was used by Lenape peoples from the Woodland period until Dutch colonization. Erosion at the site’s beach showcases remains of large shell middens.

Ward’s Point was occupied in large part by the Raritan band of the Lenape, living around the Raritan River. In 1895, archaeologist George H. Pepper was contracted to lead research at Burial Ridge by the American Museum of Natural History. Alongside human remains, many of which were found in flexed positions, were hammerstones and ax heads. Notably, the body of a child was uncovered alongside utensils and pendants, as well as potentially copper ornaments. Eventually, in 1670, Staten Island was sold by the Munsee residents in a complicated 1670 deed which was signed strangely by four random sons of the colonists.

Elsewhere on Staten Island, a village in West New Brighton was uncovered with a few traces of Native occupancy. In the neighborhood of Rossville was a shell heap, while there were likely settlements around modern-day Freshkills Park. There is also evidence of Native occupancy around the Sandy Ground and Great Kills on Staten Island.

Next, check out the Top 10 Secrets of the National Museum of the American Indian!

Subscribe to our newsletter