After-Hours Tour of "Noguchi's New York" Exhibit

Join an exclusive curator-led tour at NYC's Noguchi Museum!

On a wintry Monday evening in January 1934, big-time businessman Sidney Cohen and his friend Morris Sussman gathered a group of nine Black journalists from New York and from out of town. Cohen and Sussman, both white, wanted the writers’ input on what the Harlem “community needed,” because four days later, the pair would make a historic business move.

Although they didn’t know it yet, their new venture, which promised a “revolutionary step in the presentation of stage shows,” would transform the world of entertainment for decades to come. On Friday, January 26, 1934, they would open the doors to one of the first vaudeville halls in New York City to spotlight Black performers and welcome Black audiences — the Apollo Theater. [1]

Historians have described the Apollo as a place of mythology where legends are forged.[4]

“It’s a theater on the most important street in [Harlem] right in the middle of the community,” says Brian Goldstein, historian and author of The Roots of Urban Renaissance: Gentrification and the Struggle Over Harlem. “So, there’s this very tangible way in which playing [the Apollo] was kind of name-making.”

The Apollo gave us Ella Fitzgerald and Pearl Bailey. It’s the place where a young Black artist named Billie Holiday put on a controversial performance of “Strange Fruit” in 1959 America, the place where the nation’s first and only Black president broke into a rendition of Al Green’s “Let’s Stay Together” in 2012.

It’s hard to imagine a time before it became the Apollo, but such a time does exist. Sure, the well-known performances of the latter half of 1934 and onwards by the likes of Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan, and James Brown, stamped the theater’s name in history. But its more modest, less buzzy beginnings set the stage for what was to come.

The Harlem fixture debuted as the 125th St. Apollo in 1934. It was a “re-christened” reincarnation of Hurtig & Seamon’s Apollo Theater, a burlesque hall which had been operating inside the theater building since 1913. [2][3] Little is known about the embryonic days of the Apollo, but what is evident is that when he bought the 20-year-old building in 1933, installed Sussman as manager, and struck the “all-white” rule, Cohen rolled the dice.

Although New York had made segregation illegal by the 1920s and created laws preventing discrimination by the 1930s, many theaters in Harlem nonetheless only permitted white patrons or treated Black visitors differently, according to David Freeland, historian and author of Automats, Taxi Dances, and Vaudeville: Excavating Manhattan’s Lost Places of Leisure.

The Great Depression was in full swing, and a campaign against burlesque by Mayor Fiorello La Guardia had shuttered Cohen’s former businesses and those of other music hall owners. “Burlesque started becoming too vulgar, too risky,” says Billy Mitchell, the Apollo’s tour guide and historian. “It was promoting immoral behavior.”

Opening the Apollo amid these circumstances was a gamble, but Cohen took a risk — in the name of lucre.

Harlem wasn’t always a predominantly Black neighborhood. When Hurtig & Seamon’s, the Apollo’s predecessor, was built, the area around 125th St. was more Irish and German, says Freeland. When middle-class African American families began moving to Harlem to fill in vacant housing triggered by overdevelopment, Freeland says, “the center of African American life [expanded and moved] southward, without diminishing the areas of the [130’s streets]” which had previously been “the locus of African American culture.”

On the heels of the Harlem Renaissance, Cohen and Sussman saw an opportunity to capitalize on the growing African American population and ensure a groundbreaking premiere for the Apollo.

Not only did the businessmen solicit advice from Black journalists, but they also publicized their decision to donate all proceeds of the opening to the Fresh Air Fund of Harlem, a summer program for children from “underserved communities” – perhaps in hopes of drawing a crowd. To ensure superior audio quality, they acquired high-tech sound equipment akin to that used at Radio City Music Hall and were sure to boast about it. [5][6]

Setting up for a show at the Apollo in its early years proved arduous. An undated letter sent to the theater’s management regarding a Josephine Baker show includes sketches of the required stage configuration and requests “a large quick change room, built on stage,” “a 5-foot wide runway,” eight different microphones, and two colored spotlights, one “light pink” and the other “special lavender.”[7]

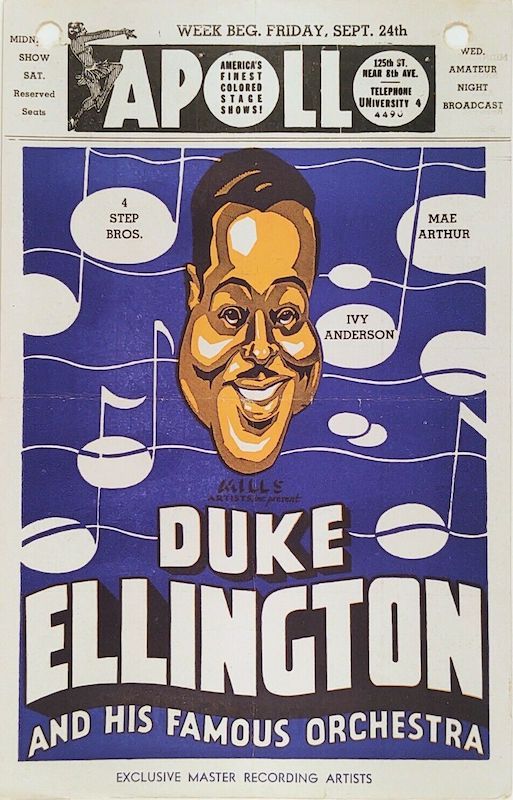

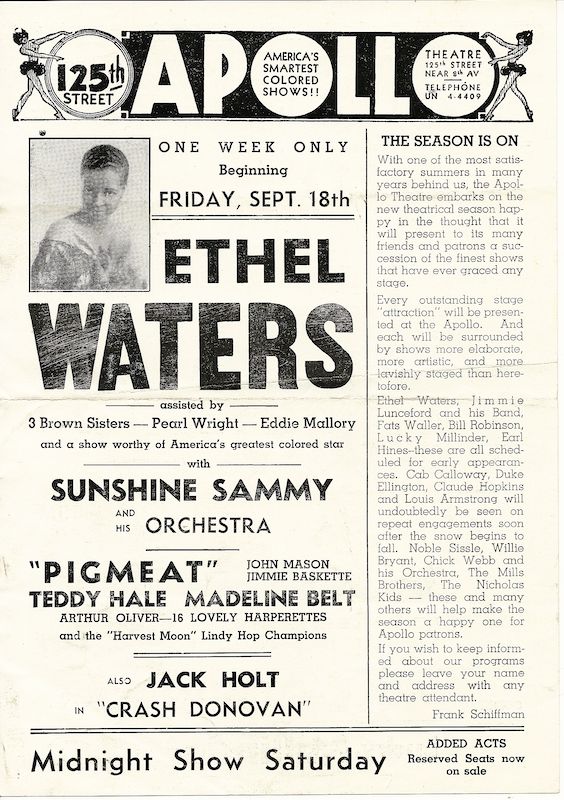

If this missive is anything to go by, Cohen and Sussman’s mise en place for the January 1934 opening was sizeable, for they would have to prepare to serve up a buffet of performances. On the menu: “Jazz a la Carte,” a smorgasbord of at least eight different acts. Jazz singer Aida Ward, showman Ralph Cooper, and multihyphenate musician Benny Carter and his Orchestra were three of the main attractions. Accompaniments included the Three Rhythm Kings, singer Mabel Scott, and a showing of the 1932 crime drama Criminal at Large.

The theater’s management was keen to cook up a storm.

Management guaranteed an “all-colored production of the best quality” and “the most lavish and colorful extravaganzas.” These promises were cemented in newspaper print. “We feel certain that the 125th Street Apollo Theatre will be an entertainment edifice that Harlem will take pride in showing off to neighborhood communities,” read an ad in the New York Age, a then-prominent African American newspaper.[8]

At 8 o’clock on Friday, January 26, 1934, the theater rose its figurative curtain for the first time with a new name and audience, in what turned out to be a glitzy occasion, according to Amsterdam News’ Roi Ottley. Somewhere in the 1,500-seat theater, Black celebrities such as actor Bill “Bojangles” Robinson and pianist Lil Armstrong, probably in their snazziest garb, watched as the theater delivered its first-ever show — the nascence of the Apollo we know today.[9]

Opening night wasn’t all glamorous, though. Some jokes fell flat, Mable Scott danced a little too much and, according to Ottley’s review, “Benny Carter’s band needs lots more rehearsing” because they hit “many a sour note.”[10]

Sour note or not, thanks to the management’s donation campaign, the theater was “packed,” an out-of-town newspaper published. The Apollo “opened with a bang,” another reporter concluded. That Friday, Harlemites ditched the other “vaud” venues in the area for a day of song, dance and comedy at the Apollo, raising $229.50 for a good cause, the equivalent of over $5,000 today. Less than 10 years before the Apollo’s opening, Black people were made to enter the 125th St. theater via a separate entrance on 126th St. Now, here they were, well-known Black guests and civilians alike listening to the warm tones of “hot jazz” by Black musicians.

Over the years, as other Black vaudeville venues in Harlem hung up their hats, the Apollo remained steadfast. Take the Lafayette Theater, for example, once perched on 132nd. This venue was owned by Leo Brecher and Frank Schiffman — who are often incorrectly credited with opening the Apollo, when instead they took over from Cohen. Or the Harlem Opera House on 125th, or the Lincoln Theater on 135th, or the Cotton Club on 145th. All have vanished into relative obscurity. [11]

“I think [the Apollo] tells us a lot about survival — survival of music, of culture, of architecture of space — because it beat the odds,” says Freeland. “So much history in Harlem has been lost.”

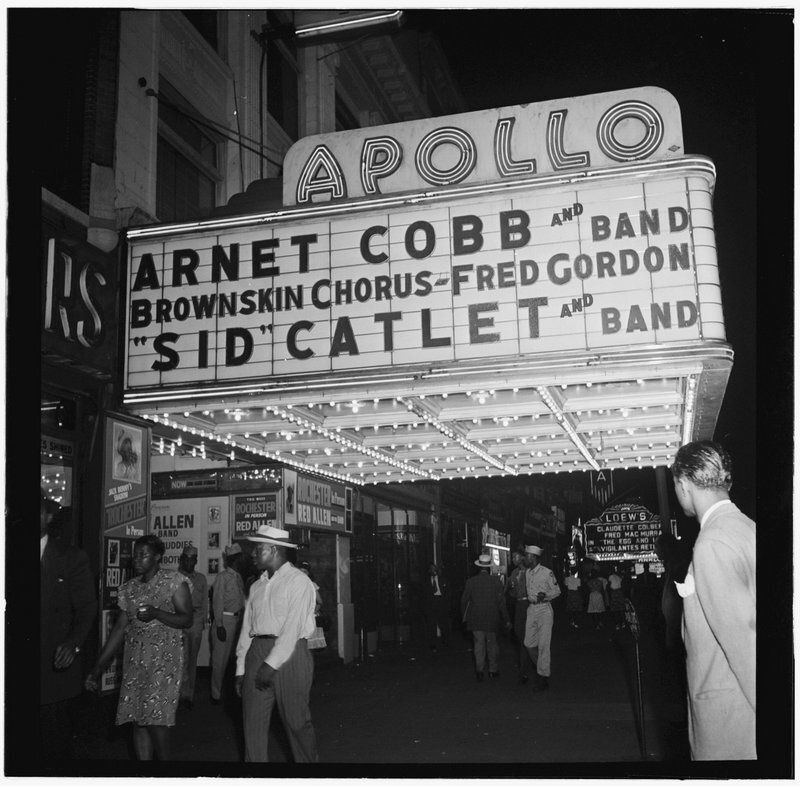

Decades since its opening, the Apollo’s Greek-inspired façade and (now-digitized) iconic marquee still distinguish it from its commercial surroundings in Harlem, but the theater has evolved. Mitchell emphasizes that the Apollo is “not just a performance space anymore.” It has grown to also offer educational community programming. Still, the theater’s mission has remained fundamentally the same.

“The Apollo Theater is not only a place where we come to see shows,” Mitchell says. “The Apollo Theater, over the years, has become the focal point in the Harlem community, where people come…to celebrate, and to mourn and grieve when one of our greats have passed on. It’s a place where the community comes to exchange ideas.”

Each year following the triumphant opening in 1934, the audience of the Apollo grew ever more Black. Little has been documented about how African American visitors were treated by Cohen and Sussman in the subsequent days and months — the theater’s culture was said to have been better than that at other venues — but Mitchell says the Apollo was a “welcoming” environment.

As the theater gained popularity and changed ownership, it began to play a key role in the nighttime routines of New Yorkers. After attending shows or playing at the Apollo, patrons and performers often stopped by Eddie Green’s barbecue rib joint on 126th St. before hopping in a cab to head to their next stop. [12]

“There’s a kind of intimacy that you get when you’re in the Apollo. You can understand how such great music was cultivated there,” says Freeland.

When Cohen and Sussman lit the Apollo stage for the first time that Friday in 1934, they created a space where Black performers could take a break from the “bitter reality” of the world outside. “In the theatre, reality was beautiful women, strong men, and angelic children,” wrote Ted Fox, author of Showtime at the Apollo. Because for Black performers, “the Apollo was home.”

The building called The Victoria is part of the Victoria Theater Redevelopment Project, a public and private partnership that includes the Renaissance Hotel, The Apollo’s Victoria Theater, and Apollo office space. The Apollo Stages at Victoria Theater include two new flexible theaters—one with 99 seats and one with 199 seats. There will also be retail shops to be announced in the building as well. The Apollo spaces (two theaters and office space) are located on the 3rd and 4th floors of The Victoria building.

You can check out all of the upcoming programming at the Apollo, including performances at The Music Café and The Apollo Stages at Victoria Theater, on the Apollo website.

Next, check out 10 Secrets of the Apollo and 10 Iconic Jazz Clubs, Past and Present

[1] New York Age, Jan 27, 1934, “Message to Harlem Theatre-Goers.”

[2] Fox, Ted. Showtime at the Apollo. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1983, pp. 7-123.

[3] New York Age, Jan 27, 1934, “New Vaudeville House to Open on 125th Street.”

[4] Schiffman, Jack. Uptown. Cowles Book Company, 1971, pp. 2-191.

[5] Chicago Defender, Feb 10, 1934, “Fresh Air Fund Nets Large Profit from Theater Benefit.”

[6] New York Age, Jan 27, 1934, “Message to Harlem Theatre-Goers.”

[7] Letter to Frank Schiffman, Undated, Smithsonian Institute, Frank Schiffman Apollo Collection https://edan.si.edu/slideshow/viewer/?eadrefid=NMAH.AC.0540_ref15

[8] New York Age, Jan 27, 1934, “New Vaudeville House to Open on 125th Street.”

[9] Fox, Ted. Showtime at the Apollo. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1983, pp. 7-123.

[10] Berger, Morroe. Benny Carter: A Life in American Music. Scarecrow Press, 1982, pp. 43-130

[11] Fox, Ted. Showtime at the Apollo. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1983, pp. 7-123.

[12] Ibid.

Subscribe to our newsletter