The Fight to Save NYC’s Endangered Languages

Untapped New York talks with author Ross Perlin about how to save an endangered language in NYC, where over 700 languages are spoken!

Seke. Wakhi. Yiddish. N’ko. Nahuatl. Lunaape (Lenape). These six languages are among the more than 700 languages spoken by New Yorkers across the five boroughs. What makes them unique is that they are endangered. In his recently released book, Language City: The Fight to Preserve Endangered Mother Tongues in New York, linguist, writer, and translator Ross Perlin turns the spotlight on six speakers of these languages, illuminating the linguistic history of New York City through their stories. Untapped New York spoke with Perlin about what it means for a language to be endangered, what goes on inside the Manhattan office of the Endangered Language Alliance, and how all New Yorkers can help combat the disappearance of little-known mother tongues.

Hear more from Ross Perlin and ask your own questions in an upcoming live virtual talk on May 2nd! This talk is free for Untapped New York Insiders! Not an Insider yet? Become a member today with promo code JOINUS and get your first month free!

Untapped New York: What initially sparked your passion for linguistics?

Ross Perlin: Growing up in New York surrounded by languages but as a monolingual speaker, like other monolingual New Yorkers, there was an ambient awareness of all these other languages but they weren’t accessible to me. As soon as I could, I started trying to learn languages at school and from friends and neighbors. It wasn’t really until I was studying Mandarin abroad in China that I encountered this Chinese linguist who made me aware of the fact that there were 7,000+ languages in the world, and as many as half are likely to disappear in the next century or two. It just blew my mind. That was the spark that led me to study linguistics and spend several years living in this remote area of southwest China documenting a particular small group of languages there.

Then I came back to New York to hear the city with new ears. I saw that this side of New York, although it was something everyone knew on some level, that it was a very linguistically diverse city, it went much further than everybody realized. There were hundreds of languages around us that nobody except a few specialists and speakers of that language were aware of.

Untapped New York: What makes a language endangered?

Perlin: It’s a number of factors. Certainly, the number of speakers is relevant. Some of these languages have very few speakers, but the key factor is intergenerational transmission. Is it getting passed on to children? Once that very normal fundamental process stops, generally speaking, it’s really hard to bring the language back. It can be done, but one generation of broken or fraying transmission can really rupture a language.

In terms of the factors behind that, why would parents or grandparents stop passing on a language? There are a number of pressures involved. It’s anchored in power and the politics of history and the fact that larger languages, we don’t even think about it, but they have so many powerful forces behind them. They’re the languages of education, of media. They’ve been the languages of colonial empires, and now of nation-states that make them official. There are really so many factors behind these languages.

Also, the attitude people have about their mother tongues becomes internalized because you’ve been told again and again if a language is not written then it’s not a real language, if it doesn’t have a word for iPhone or AI somehow it’s not modern, but in reality, from a linguistic point of view, all native languages are equally sophisticated in terms of what they can communicate. That is sometimes hard to communicate given these very lopsided power relationships between languages.

Untapped New York: What is the Endangered Language Alliance (ELA) and how did you first become involved?

Perlin: In 20210 this motley crew of linguists, language activists, poets, artists, and interested New Yorkers had come together to form a sort of clubhouse really or meeting place for those who cared about the city’s linguistic diversity. It was very open. I went to an event and I was very drawn in. I proposed some different ideas based on the languages I had some knowledge of, including Himalayan languages that I had been researching in the Himalayas, and then realized that there were actually dozens of languages from that general region of the world spoken here in Queens and Brooklyn.

I gradually began to get involved, to see the magnitude of the story, and to get to know some of the people who would become the speakers of six different languages from different parts of the world who are profiled in the book.

Untapped New York: What is a typical day like at the ELA office?

Perlin: A whole range of things happen here in this funny little space on 18th street. Language activists are coming to work on their projects and to meet and at times hold classes and events and workshops, and at times to record in our little audio and video booth. Speakers from very different languages get to meet each other and have great encounters. A lot of our work takes place around the city as well, going to homes and community centers and elsewhere in the neighborhoods. There are so many communities [of endangered language speakers], especially in the outer boroughs.

Here on 18th Street, it’s a huge range [of work we do on languages]. Some languages are comparatively well documented where [the work] is really about doing an oral history, or planning some kind of fun event, or publishing a new set of children’s books. For some other languages, there may be nothing, so what we’re doing here is making some of the first recordings that may exist as well as trying to edit a dictionary and trying to figure out how to write a primarily oral language.

Untapped New York: I found it so interesting how in the book, one of the speakers, Husniya, was using children’s books as a tool to preserve language.

Perlin: Husniya has made a real priority of children’s books and has published six that we’ve done together in six different languages. These are among the first children’s books in these languages of Tajikistan. It really makes you think about how much we take for granted, with larger languages, that there will be dictionaries and grammar and clear authorities. In terms of children’s books, you can just go around the corner to the store and buy one. You just can’t imagine that for many languages there really are none and you have to make your own and all the choices that go into that are painstaking.

Untapped New York: When did you realize that a book might be a good way to get the word out about this topic of endangered languages?

Perlin: I’ve been Co-Director [of ELA] since 2013 so the research really started over 10 years ago. I was always taking notes on extraordinary moments that were happening in the office and getting to know the characters who became the main people in the book.

I thought that a book that was both a linguistic history of the city and a portrait of it today, that dealt with the past, present, and future of the world’s most linguistically diverse city would be a book—for all the books that have been written about New York—that would still be a unique one. I started writing about five years ago and it accelerated during the height of covid when I realized the urgency to document what I could see.

When I was initially getting involved [with the ELA] I thought, “Wow, it’s just going to get more diverse and interesting over time and we’ll just keep growing!” But now the threats and changes to immigration brought by COVID and other emergencies of recent years have made me realize we can’t take it for granted, that we have to be actively trying to support and grow [the city’s linguistic diversity].

Untapped New York: Since there are so many languages and speakers with whom the ELA has worked, how did you whittle it down to the six people featured in the book?

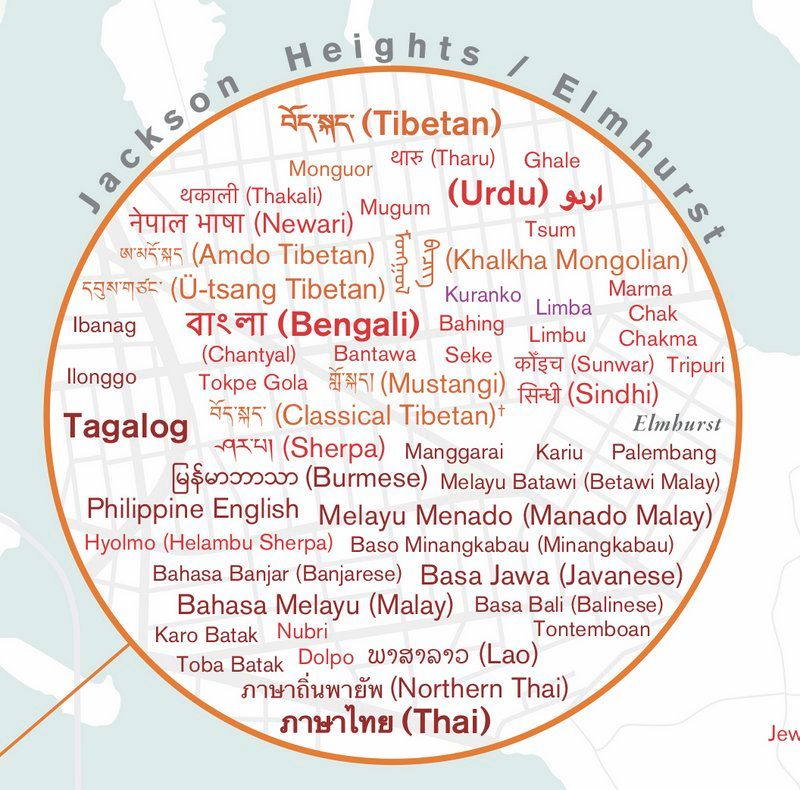

Perlin: That was hard. On the one hand, we have the language map which shows over 700 languages in counting and we have our growing digital archive and our YouTube playlist, all of which encompass recordings in well over a hundred languages. There are so many more stories.

In all the parts that have to do with linguistic history, I try to mention as many communities as possible. ln general, the larger communities that everybody knows, like Korean, Russian, Bengali, of course, they’re in there somewhere, but you can find other sources about those. I really wanted to talk about and emphasize communities I think in various ways are very significant to both the history of the city and its life today, but that you really couldn’t find anything else about.

Many of these groups, there’s barely any literature about them at all and almost nothing about their presence in New York. I also wanted to have portraits of living breathing current people that I knew well, and that I worked with over the years in different ways, each of whom represented something different about language and the fight to preserve mother tongues. Ideally from different parts of the world too, different continents, different migration stories, and different religious, cultural, and other backgrounds. The languages themselves are structurally and grammatically different from each other.

It was essential that Lenape be one of them as the indigenous language of the city. We had a strong relationship with a teacher, Karen, who unfortunately passed away before the book came out. The story of Yiddish was the story of my family as well as one that had a lot of connection to the city’s history. Each [language] had a strong reason that I felt it had to be [in the book]. Ideally, there would have been room and time for more, but even those six individual speakers between them know over 30 languages. They’re super multilingual. Talking about speakers of Wakhi from Tajikistan, there is a chance to talk about Central Asian languages. Irwin, the Nahuatl speaker from Mexico opens up a whole discussion of the indigenous languages of Mexico and even more broadly of Latin America. Each one is kind of a window into a world.

Untapped New York: What was the most surprising thing you learned while putting the book together?

Perlin: Many things are not quite what you think they are. Initially my view of linguistic diversity, maybe like many New Yorkers, was that it’s based on enclaves. You could go from Chinatown to Little Yemen to Loisaida (the Puerto Rican Lower East Side). That there were these clear distinct enclaves. Part of mapping the city’s languages and writing the book was realizing how much more complex and intricate, even at the level of every building and every street, the linguistic geography of the city can be.

I describe in the book, vertical villages, where you can have a whole portion of a group or a literal village, that is in a way transplanted or reconstituted in New York, but there’s no such thing as a monoethnic enclave. There’s always diversity within. The deeper you look, the more complex it gets. Everything is much more woven together, the essence of it is contact, interaction, and multilingualism.

Untapped New York: What are the benefits and challenges to endangered languages being in New York City?

Perlin: The presence of languages from all over the world, including many minority, indigenous, and endangered languages, is an opportunity for New York and other cities. This isn’t unique to New York but New York is perhaps the real paradigm case because it’s been a multilingual immigrant gateway city for longer than anywhere else. Speakers of these languages are bringing all of their knowledge and cultures, music, poetry, oral literature, recipes, and knowledge of plants. All these things they are bringing to the city are things we’re all benefiting from even if we’re not directly aware of it.

Generally, I describe the city as sort of being a sieve that languages are running through. We haven’t been good at actually appreciating their presence and holding the knowledge [speakers] bring. The pressure to shift languages grows even stronger when people arrive here, not just switching to English but switching sometimes to Spanish or Russian or to other larger languages that are significant here.

The city can present opportunities that I talk about in the book. For activists to revive their languages, to hold on to their languages, there are platforms here. We like to think the Endangered Language Alliance is one. Even just a speaker—we see this all the time—recording something in their language from Times Square and feeding it back to people on the other side of the world can create a certain pride that the language is here in a major visible city. There are challenges and opportunities and I’d love to think New York will fulfill its promise as a beacon of linguistic diversity that doesn’t just receive all of this, but actually grows and sustains and celebrates it actively.

Untapped New York: Is it possible to “save” an endangered language?

Perlin: There are stories of linguistic success with reversing language shift and revitalizing languages and bringing them back. I wouldn’t say saved, but the level of documentation can become significant where there are now serious resources, good quality accessible resources preserved in an archive for the long run where community members have the option to do what they wish with the language.

There are extraordinary cases with languages like Hawaiin or Maori where speakers reversed the tide and are producing lots of new speakers, many second language speakers, but also native speakers. It’s happening with a lot of Native American languages. There are an increasing number of cases around the world where exciting things are happening and even exciting cases in New York where it seems like at least the pace of language loss is being slowed down and a new set of awareness and set of attitudes are coming in. Nothing is forever, but it is possible under extraordinary circumstances and with enough mobilizations to turn the tide.

Untapped New York: How can New Yorkers get involved with the ELA?

Perlin: A lot of our projects start with speakers contacting us or the children or grandchildren of speakers contacting us. Since Language City came out, we’ve heard from speakers of languages from Cameroon, from Italy, and more that we didn’t know where here in New York, so speakers are all around. Our language mapping and our work are very open-ended. We’re constantly updating https://languagemap.nyc/ and we love to hear from people who either speak a language or have a connection to or idea to work on a language that has fewer resources or is less well known. That includes different dialects of different languages. There’s not always a clear distinction there.

For people who don’t really have that connection, there are still ways to get involved. You can come to our events where we bring languages rarely heard to a stage, donate, read the book, or follow the language map. There are various ways to be involved. We’re a shoestring operation but we’ve been around for a while and we hope to be around for a while longer as a unique place focused on urban language diversity which, as far as we know. there’s no other organization quite like it.

Untapped New York: What’s the biggest takeaway you hope readers get from the book?

Perlin: Especially for readers of Untapped New York, who are already so much attuned to the city, I hope this opens up another dimension in their appreciation of New York and other cities as intensely multilingual spaces where, even if you can’t understand what that person next to you on the subway is speaking, you are aware of and open to the extraordinary linguistic diversity that is all around us, and when possible you also take steps to support that in various ways. From the level of your awareness to policy to your neighbors. I hope it opens up…people’s understanding of the city, bringing languages within earshot.

Grab your own copy of Language City: The Fight to Preserve Endangered Mother Tongues in New York here and join Ross Perlin for a live virtual talk about the book on May 2nd!

Next, check out NYC’s Last Spanish-Language Bookstore