After-Hours Tour of "Noguchi's New York" Exhibit

Join an exclusive curator-led tour at NYC's Noguchi Museum!

From its days as a freight railway and abandoned wasteland to its current state as a beloved park, uncover secrets of the High Line in NYC!

In 2009, the High Line was hailed as the savior of the declining West Chelsea neighborhood. Fifteen years later, the area surrounding this now beloved “park in the sky” is bursting with food, art galleries, and new development. The High Line opened in 1934 and was used by freight trains for twenty years. When the railway closed, the elevated tracks became an abandoned infrastructural wasteland above Chelsea overgrown with wild plants. Many talked of demolishing it for good.

Thankfully, efforts by the community and various organizations like the nonprofit Friends of the High Line campaigned for its renovation in the late 1990s. After years of planning and construction, the elevated railroad became an elevated park, attracting millions with picturesque urban views, unique art installations, and diverse plant life. Here, we explore some of the High Line’s secrets, with insight from On the High Line: A Definitive Guide.

In On the High Line: A Definitive Guide, historian and author Annik LaFarge takes High Line walkers and armchair tourists on a journey through the history and sights of the park. Section by section, LaFarge reveals hidden stories of historic landmarks and new developments visible from the High Line, provides insight into the park’s innovative architectural and horticultural design, and explores how the High Line forever changed the west side of Manhattan. This newly revised guidebook can be enjoyed whether you’re out on the High Line or sitting at home. More than one hundred black-and-white images dating from the early 1900s to the current day illustrate the High Line’s evolution. Hundreds more color photographs can be found on the book’s companion website.

We celebrated the 15th anniversary of the High Line with Annik LaFarge! Check out the recording of our talk with the author in our Insiders on-demand archive which contains over 250 recorded webinars.

Not an Insider yet? Become a member today with promo code JOINUS and get your first month free!

Before the advent of widespread subway systems and an elevated rail, street-level trains ran on 10th and 11th Avenues. To ensure at least a bit of safety, the city passed an ordinance that required men on horseback to ride ahead of the trains and warn people of the oncoming vehicles. “West Side Cowboys,” as they came to be known, would wave red flags in front of trains (red lanterns at night) and help civilians cross the busy streets. For various reasons, from impatience to poor visibility, people often ignored the warnings of the Cowboys and attempted to run across the tracks whenever they needed to. This often resulted in tragic collisions with the oncoming freight train. These gruesome incidents occurred so often that 10th Avenue earned the nickname Death Avenue.

The High Line was constructed as an above-ground train track partly because of the number of accidents in the area. The city debated what to do about the danger for quite some time. In 1929, the City endorsed Robert Moses’ West Side Improvement Project, which called for an elevated highway running through Chelsea. The High Line Railroad opened on June 28th, 1934.

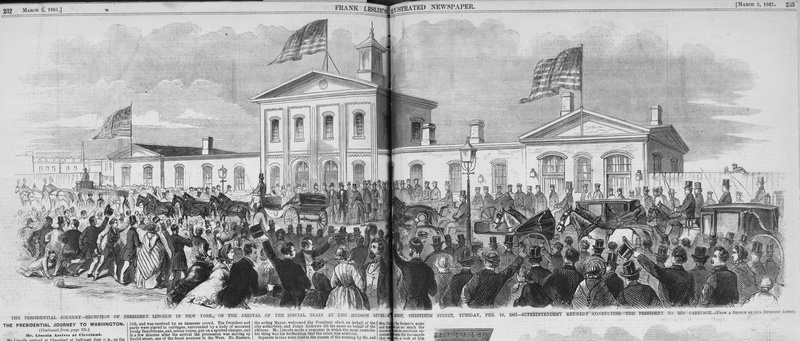

Abraham Lincoln was the first passenger to pass through the Hudson River Railroad train station at 30th Street and 10th Avenue in February 1861. He stopped in New York City on his way to Washington, D.C. for his presidential inauguration. Four years later, Lincoln passed through the station again, this time in a casket.

The president’s body arrived in New York City via ferry days after he was assassinated. More than one hundred thousand mourners paid their respects at City Hall where Lincoln’s casket laid in state. The next day, a funeral procession traveled uptown to the 30th Street train depot where Lincoln’s body was sent to Illinois.

At the former site of the 30th Street train station walkers along the High Line will now see The Morgan General Mail Facility. This structure was built in 1933 and designed to have the High Line run through it. A plaque on the facade commemorates the two times Lincoln passed through the area.

In its first few decades of operation, the High Line was considered the “lifeline of New York.” Necessities like dairy, meat, and produce were carried along its tracks. However, as the 20th century progressed and alternative modes of shipping like interstate trucking and air travel replaced freight trains, the High Line became less vital. The final train journey atop the elevated tracks took place in 1980. The cargo on that last train was three boxcars full of frozen Thanksgiving turkeys.

A group of landlords who saw the potential for real estate development in the Chelsea area campaigned to have the entire railway, then a waste of space, demolished. Preservationists responded with a campaign to “Save the Tracks” led by Chelsea activist Peter Obletz.

The park’s journey to renovation really began when it was officially slated for demolition after having been partially dismantled by Mayor Rudy Giuliani’s administration. Friends of the High Line became involved, raised money, and a plan to renovate the space into a public park was born. See more photos of the park’s abandoned third section before construction here.

After railroad operations ceased, the High Line sat abandoned for decades. Over time, the rails started to rust and weeds grew out of control. The elevated railroad became a popular destination for urban explorers and graffiti artists (and would have most definitely made for an exciting abandoned site in the 80s). Colorful bursts of spray paint covered the walls of neighboring buildings and the steel fences of the old rail line. The Chelsea Passage, a former rail tunnel where dairy trains would deliver supplies to the Nabisco factory, became a guerilla art gallery. In the photo above taken by Rick Darke inthe 1990s, you can see a guerilla sculpture welded directly to the old tracks.

Once the railway was transformed into a park, art remained fundamental to the sites identity. For years, the Chelsea Passage was home to The River That Flows Both Ways, a subtle installation produced in partnership with Creative Time. The passage now serves as the park’s open-air food court and hosts temporary exhibits.

When the project to renovate the railway was green-lit in 2003, Friends of the High Line held a design competition to find the best approach for reinventing the space. The winning design came from landscape architect Field Operations, architects Diller Scofidio + Renfro, and horticulturist Piet Oudolf.

Original pieces of the High Line, including the 1930s railroad tracks, were integral to the new park’s design. LaFarge writes in On the High Line that during the remediation of the old rail bed, all of the original metal tracks were removed. The architects devised a labeling system with letters and numbers to ensure each piece returned to its original location. Each piece of rail was marked according to this system with yellow paint. You can still see the vestiges of this system along with old signal lights and switch devices (called frogs) that were once part of the rail system.

When it was completed in the 1930s, the High Line ran for over 2 miles from 35th Street and 11th Avenue to St. John’s Terminal just south of Houston. It passed through dozens of buildings, including the Nabisco factory (now Chelsea Market). After the railroad ceased operation, nearly half of the line was torn down. From Gansevoort Street to Clarkson Street, only one isolated piece of the High Line remains.

This 235-foot stretch of forgotten track cuts through Westbeth Artist Housing between Bethune and Bank streets. Before becoming housing for artists, this 13-building complex was the home of Bell Telephone Labs. Before that, it was a laboratory for Western Electric, the company that built the complex in 1868.

Trains once barreled through the building’s 2nd and 5th floors, creating strong vibrations and sounds that affected lab instruments. Special accommodations had to be made to the building to quell these disruptions. Today, the tracks are quiet and overgrown with vegetation.

The High Line boasts 450 species of plants spread across various environments from woodland thicket and prairie grassland to bog and perennial meadow. Among the evergreens and deciduous trees of the Chelsea Thicket between 21st and 22nd Streets, one plant grows as an homage to Clement C. Moore. Moore is most well known for being the author of “A Visit from St. Nicholas,” also referred to as “Twas the Night Before Christmas,” but perhaps less known for his connection to the High Line.

The High Line cuts through land once owned by Moore’s family. In 1750, Moore’s grandfather, Captain Thomas Clarke purchased a large swathe of property and named it Chelsea after Chelsea Hospital in London. As the property was passed down, it was expanded to encompass land from West 19th Street and Eighth Avenue to West 24th Street and the Hudson River. Moore would later donate part of this land to the General Theological Seminary. Due to his connection to the Christmas holiday and the history of Chelsea, Moore is remembered on the High Line with an American Holly bush.

The High Line can be categorized as the world’s longest green roof! Believe it or not, the average depth of soil is only 18 inches. This shallow soil depth posed a challenge for water conservation and drainage. The park uses multiple levels of filters and drainage systems to collect, store, and distribute falling rainwater to its plants.

The system starts at the very top level with pathways designed specifically to direct rainwater into the plant beds. Once in the plant beds, the water soaks into multiple layers of soil, from the topsoil to sub-layers of clay, fabric, and gravel. At the bottom, a drainage mat covered in egg carton-shaped cups reserves water to be absorbed back into the soil when conditions are dry.

Hector’s Diner is where all the diner scenes for Taxi Driver starring Robert DeNiro were filmed and where many Law & Order episodes were shot. Currently, it sits nestled under the High Line, surrounded by chic boutiques and expensive eateries, a stone’s throw from The Standard Hotel.

In the 1930s, the Meatpacking District produced about a third of the country’s meat. Hector’s used to open at 2 am for employees clocking in for their shifts. Though Hector, the original owner, is long gone, the diner is still open and has proven to be one of the city’s sturdiest businesses.

Look familiar? The Coulée Verte René-Dumont is in the 12th arrondissement of Paris, built in 1993 out of a repurposed railway. It follows the old Vincennes railway line and crosses an elevated viaduct called Viaduc Des Artes as it reaches the Bastille. Retail shops are housed within the arches of the viaduct. This park inspired the High Line and in turn, the High Line has inspired more infrastructure parks around the world.

Friends of the High Line even runs an initiative to support infrastructure reuse projects. A few projects in the High Line Network include the Riverline in Buffalo, The Underline in Miami, and The Meadowway in Canada. As of 2023, the Network expanded to just under 50 projects.

Next, check out Secrets of Madison Square

This article was originally reported in 2015 by Jinwoo Chong and updated in 2024 by Nicole Saraniero

Subscribe to our newsletter