When photographer and urban explorer Joseph Anastasio stumbled upon an abandoned passenger car sitting dormant in the Brooklyn Navy Yard, it was like an apocalyptic scene from the latest season of The Last of Us. The derelict car was a forgotten prototype from the Brooklyn-Queens Connector – commonly known as the BQX – a $2.7 billion light-rail project that never saw the light of day. Check out more of Anastasio’s photos below and find out what happened to this failed transit project Untapped New York has been following since 2016.

Origins of the BQX

The BQX was conceived before the DeBlasio administration. The original idea can be traced back to the late-urban planner Alex Garvin who became known for the “Ground Zero: The Rebuilding of a City.” But Christopher Torres, the former deputy director of the Friends of the BQX, credits an article written by New York Times critic Michael Kimmelman for the vision behind the BQX.

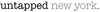

In 2014, Kimmelman published an op-ed suggesting the city return to its roots and adopt a streetcar system independent from the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA). He invokes the term “desire lines” to describe emerging neighborhoods along the Brooklyn and Queens waterfront that were largely underserved by the existing subway lines. Hoping to bring Kimmelman’s idea to fruition, Friends of the BQX proposed an 11-mile streetcar line that would run along the East River From Astoria, Queens to Red Hook, Brooklyn.

In 2017, Friends of the BQX hosted a press conference at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. The organization unveiled a prototype of the BQX, a 46 by 9-foot passenger car designed by Alstom SM. The French rail transit designer previously worked in other major cities like Miami and Toronto. The prototype looked quite futuristic. It had a sleek exterior, open gangways, and bright red seats.

When Anastasio, author of Brooklyn Navy Yard: Beyond the Wall, found the abandoned prototype back in March, he “was surprised at how abandoned it felt: with panels falling off and quite a bit of liter inside the two cars.” It appears that the seats were removed as well. “Overall I was surprised at how narrow it was,” he continued, “The seats were laid out funny. It just felt oddly uncomfortable.” You can see before and after photos below.

By the time of the prototype unveiling, the project was beginning to hit its stride. Friends of the BQX had assembled a formidable board of directors, including representation from developers, city agencies, and business improvement districts—a who’s-who of Brooklyn and Queens power brokers. Through canvassing, cold-calling, and engagement workshops, the non-profit also gathered over fifty thousand signatures from residents supporting the project, many of whom resided in New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) facilities.

Why the BQX Was Never Built

While the inspiration for the BQX preceded DeBlasio, the project was both a beneficiary and a victim of his administration. Before the pandemic, New York was trying to capitalize on the tech boom taking over cities like San Francisco. When Long Island City emerged as the leading candidate to host Amazon’s new headquarters, it was clear the subway was no longer sufficient, especially in the outer boroughs where young professionals were beginning to settle. In comes the BQX. The project was to be funded through deferred financing, essentially that means it would have been funded retroactively using the property taxes it would generate. This has become standard real estate practice in New York, paving the way for unprecedented real estate projects like Hudson Yards.

It’s nothing new for transit proposals to be co-opted by politicians hoping to give their constituents something tangible to rally behind. But with Governor Hochul’s controversial decision to hastily suspend congestion pricing–leading to $16.5 billion in budget cuts at the expense of subway extensions–depoliticizing public transit has never been more relevant. As a community-led project, the BQX claimed to do just that, bring ingenuity and efficiency to an antiquated transit system. “For the first time in over 100 years,” Torres said, “transit was back in the hands of the city.” The Friends of the BQX hoped to build off the success of previous grassroots organizations that mobilized public works initiatives, namely the Friends of the High Line.

But it wasn’t clear whether the BQX would fill the transit void on the Brooklyn-Queens waterfront. Opponents of the plan argued that sections of the initial route were redundant with the MTA’s existing G line. Torres rejects the notion that the project was mutually exclusive from existing subway lines however, “The BQX was part of a holistic plan, one that included bolstering the MTA.” As a result, the route was constantly being tweaked and pivoted away from residential neighborhoods like Sunset Park to more commercial markets like Downtown Brooklyn. As consulting fees mounted, the project’s $2.4 billion price tag grew. When Amazon withdrew from its Long Island City project, the $40 billion the BQX had promised to generate in tax revenue seemed suddenly out of reach. Covid’s impact on the city’s budget was the nail in the coffin.

As for the prototype, Anastasio told Untapped New York it was recently dismantled. “I’m bummed it’s gone…they totally could have placed it in a playground and let some toddlers run wild. Heck, if they tried to sell it I might have bid on it,” he said.

The BQX Legacy

Enthusiasm for bringing a light rail system to Brooklyn and Queens still remains. This fervor inspired Governor Hochul to resurrect the Inter Borough Expressway (IBX) in 2022, an adaptation of the Regional Planning Association’s Triboro RX project from 25 years ago. Just like the BQX, the IBX would serve transit deserts across Brooklyn and Queens, using Long Island Railroad tracks to establish a route from Jackson Heights to Bay Ridge. Unlike the BQX, the IBX would fall under state supervision. Proponents argue that Hochul’s seal of approval might smooth tensions between the City and the State.

It’s hard not to wonder whether the IBX will come to the same fate as its predecessor. Despite its demise, the BQX was part of a larger, nationwide movement to democratize public transit by establishing a light rail system that is transparent and locally controlled.

There is genuine interest amongst New Yorkers to revamp our public transit and make it match the world-class city of New York, to make it more eco-friendly, accessible, and efficient. But the subway is ubiquitous, fundamental to how we understand the city, both above and below the ground. The BQX captured the imagination of a fervent base of supporters, but will its legacy fade away like the remnants left to rust in the Brooklyn Navy Yard?

.Next, check out our Top 10 Secrets of the Brooklyn Navy Yard