10 Fun Facts About Opening Day of the NYC Subway on October 27, 1904

As the 120th anniversary of the subway approaches, take a look back at the events of the NYC subway opening day on October 27th, 1904!

By reading first-hand accounts of the opening day of the New York City subway, October 27, 1904, you get a picture of the excitement, madness, and sheer feat of the construction of the underground system. The first subway line, the Interborough Rapid Transit, ran from the glorious City Hall subway station (now decommissioned) to 145th Street, proclaiming “City Hall to Harlem in 15 minutes,” though as you’ll discover, even the first day wasn’t without delays. Here are some of the fun facts that we found from reading reports from The New York Times and the Chicago Tribune about opening day!

Justin Rivers gave a virtual talk for Untapped New York members about the lead-up to and legacy of opening day, which you can watch now in our video archive!

1. The Mayor of New York City Drove the First Subway Train (And Wouldn’t Give It Back)

While New York City Mayor George B. McClellan may have been a bit un-fun as a mayor, revoking motion picture licenses (apparently, movies were a danger to the morals of society), he showed some spirit on October 27, 1904, the day the subway opened. He was given the honorary duty of starting the first train at City Hall station and was supposed to give the controls over to an IRT motorman but instead, he took it all the way to 103rd Street. Replying to the query “Don’t you want the motorman to take hold?” McClellan said, “No sir! I’m running this train!” The New York Times referred to McClellan as the “Mayor-Motorman” in a 1904 article about the opening ride.

2. A Silver Controller Was Made Just For the Opening

Delivered in a mahogany case, the silver controller for the first New York City subway train was inscribed with the message: “Controller used by the Hon. George B. McClellan, Mayor of New York City, in starting the first train on the Rapid Transit Railroad from the City Hall station, New York, Thursday, Oct. 27, 1904. Presented by the Hon. George B. McClellan by August Belmont, President of the Interborough Rapid Transit Company.”

Apparently, however, the silver controller wasn’t quite the right size, as noted by The New York Times. IRT General Manager Hedley remarks, “Doesn’t fit very well,” after the controller was fitted on the motor. As a result of the bad fit, the emergency brake lever got pulled in the first few minutes of the ride, “causing a violent jolt, a sudden stop,” with passengers “thrown forward as though the train had struck an obstruction,” writes The New York Times. Hedley makes a quick adjustment and the rest of the ride is fine.

3. A Lot of People Snuck In To Ride the First Train

The first New York City subway was obviously a big deal to residents and six to seven thousand people came to wait outside the opening exercises in City Hall. Two hundred policemen were ready, forming a line to hold back the crowd. Despite the police force, many were able to slip in. As a result, The New York Times reports, “both the two sections [of the same train] were crowded uncomfortably. Many passengers stood in every car, and the total loads probably aggregated at least 1,100 passengers.”

In addition, people were trying to get on the train from other stations, although the afternoon passes given out were not to be used on the first train. A police inspector, in plainclothes, tried to get on and was refused. The Chicago Tribune describes the mob as utilizing “football tactics.”

4. Wooden Inspection Trains Ran Before the Official Opening

Earlier in 1904, inspection tours of New York City ran on wooden cars. Mayor McClellan joined an IRT inspection tour with contractor John B. McDonald and other New York City officials.

5. The First Passengers Didn’t Like the Advertisements

While advertising is a fact of life in the New York City subway today and we even wax nostalgic when we see them in the vintage subway cars, it was noted that the first passengers didn’t like the ones in the station. Before the opening, the stations had been free of advertising. “Until then the stations had depended on their beautiful mural ornamentation for decoration. Everyone in the train was expressing regret that the fine appearance of things was to be marred,” writes the Times. And Mayor McClellan was just as upset, saying he didn’t know about the ads in the subway stations until then and admitted that from an artistic standpoint, “They look very bad.”

6. A Woman Was the First Person to Buy a Ticket for the NYC Subway

At 7 pm on October 27, 1904, the subway officially opened for paying fares. The New York Times points out that men had nickels and “lone women” had their “inevitable five pennies.” But despite the nickels of the men, the first person to buy a ticket was a “middle aged woman from Brooklyn,” writes the Chicago Tribune. She waited at the front of the line for two hours, shorter than the wait for cronuts on some days. However, the New York Times says the first green ticket was sold to H.M. Devoe, a Deputy Superintendent in the Board of Education, but maybe given his title he got some special treatment.

7. 15 Diamonds Were Lost on the First Day of the Subway Opening

The third man to buy a ticket, Henry Barrett who lived on West 46th Street, took the first train at 7:02 at 28th Street. At 7:03 he says he looked for his diamond horseshoe pin with 15 diamonds (or 15 carats according to another report), but it was missing. With a value of $500, it would have been worth over $15,000 in 2024 dollars. This very first crime in the New York City subway was reported with seriousness by the Times: “The thieves will be looked for and the pawnshops watched.”

8. The First Subway Delay Happened on Day One of the NYC Subway

We are used to delays on the New York City subway system, but the very first delay happened on day one. At 6pm, a fuse blew on an express train at 96th Street and the mechanics couldn’t figure it out. The train was pushed to 145th Street for repair and the total delay on the tracks was 20 minutes. Fortunately, the first train for the public didn’t start until 7 p.m.

9. Subway Etiquette Was Already a Concern on the First Day

The Chicago Tribune asks, “Will there be a subway ‘hog’?” quoting a “young man in spectacles” riding the subway that first day:

“Now here’s a social problem. What kind of hog will the underground develop. Of course, we know the end seat hog, the stinking cigar hog, and the sprawling hog with his feet in the aisle for people to stumble over. They are always with us and of course they will follow us underground.”

This early precursor to manspreading and the MTA etiquette campaign proves that while some things change, many things stay quite the same.

10. The City Hall Subway Station Is No Longer Open

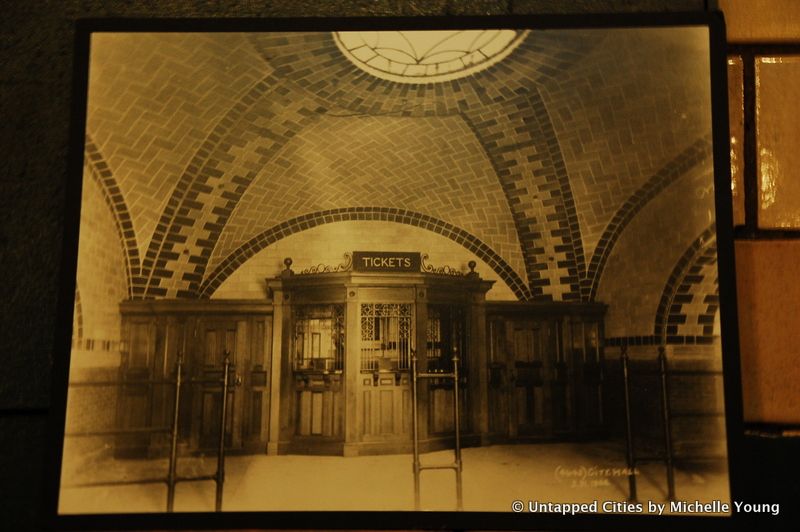

The City Hall station with its beautiful architecture and curved platform was intended to be a showpiece of the Interborough Rapid Transit Company’s (IRT) new subway line. It was also the chosen place for hanging the commemorative plaques dedicated to those who designed, built, and financed the underground train system.

The station was closed just a few decades later in 1945 because its curved platform wasn’t able to accommodate the IRT’s newer, longer cars. Today, the subway stop still remains closed but you can get a quick glimpse of the platform by taking the 6 train past its last stop at Brooklyn Bridge. For those who want a full-blown tour, you can become a member of the MTA Transit Museum to access the City Hall station on a guided tour.

Bonus: The First Known Video Inside the NYC Subway from 1905

Black and white footage was taken inside the New York subway system in 1905, seven months after the opening of the metro system in October 1904. The subway travels from 14th Street to 42nd Street along the IRT Line, which ran at the time between City Hall and 145th Street. According to France’s Le Monde (translated) ”To shoot this trip, a camera was installed in front of a subway train, itself responsible for following another car located a few meters ahead. The device also includes an engine, running on a parallel track, built specifically to illuminate the tunnels between stations.” See the footage in our virtual talk with Justin Rivers!

Underground NYC Subway Tour

Ride through the oldest stations, uncover hidden art, and more!

Next, read about more Secrets of the NYC Subway system.