Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

From an iconic skyscraper facing one of the city’s oldest squares to a former museum hiding in plain sight as a neighborhood pharmacy, Art Deco architecture is widely dispersed across Montreal. Defining elements of Northern Deco, as architectural historian Sandra Cohen-Rose calls Montreal’s version of the style, include the frequent use of bas-relief, often with themes expressing a building’s function or location, and vertically oriented facades emphasizing a building’s height, even though most are low rises. Horizontally oriented Streamline Moderne designs from the mid to late 1930s, though less common, are also present. Art Deco in Montreal also can be called the Style Camillien Houde, in honor of its biggest patron, the city’s mayor who commissioned many public buildings during the 1930s to provide jobs during the Depression. Whether you’re planning a trip to Montreal or want to vicariously experience its architectural charms, here’s our showcase of many of its Art Deco delights.

Université de Montréal Main Pavilion: Now Called the Roger Gaudry Building

Université de Montréal Main Pavilion: Now Called the Roger Gaudry Building

The Université de Montréal main pavilion is both a Montreal Art Deco pioneer and the city’s final great work in the style. Conceived in the 1920s as a French-Canadian academic acropolis on the northwest slope of Mount Royal, it wasn’t completed until two decades later.

Architect-engineer Ernest Cormier commenced his work in 1924 and by 1927 developed the general plan, which features a central section topped by a tower, with a series of mid-rise wings forming a single interconnected complex that at its outer limits extends about 960 feet long by 850 feet deep.

Université de Montréal: Main Pavilion Central Tower

Cormier was a master of integrating diverse influences. Here the formal arrangement reflects his training at the École de Beaux-Arts in Paris, while its geometric aesthetic, including verticality of the facade, stamps it at the leading edge of Art Deco. It is symmetrical, but not slavishly so, variations such as different types of windows and the shapes of secondary towers reflected programmatic considerations. One of these, a university hospital, never came to fruition but the design was modular enough to allow for an adjustment to other functions. Yellow glazed brick was picked for its durability and to lighten what might have come across as heavy and foreboding at this scale if stone or darker brick was employed.

Université de Montréal: Main Pavilion Lobby

Foundation work began in 1928 but construction stalled in the 1930s due the Depression and it wasn’t inaugurated until 1943. Its lack of applied ornament seems appropriate as its beauty is in its scaling and abstract expressions, although cost containment was also a concern.

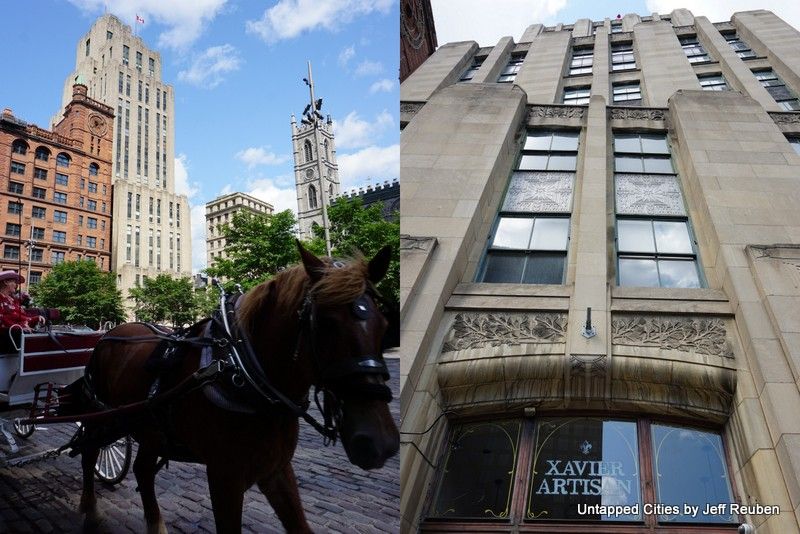

The Aldred Building (1931) is the “foremost realization in the city [of Montreal] of the romantic image of the New York skyscraper” according to Canadian architectural historian Susan Wagg. Resembling Art Deco works of Ralph Walker and Raymond Hood, this 23-story story edifice is emphatically vertical, with pilasters extending its full length, interrupted only by a series of setbacks that complied with local building height by-laws modeled on New York’s 1916 Zoning Resolution.

In fact, New York was in the Aldred’s DNA. Its Montreal-based architect Ernest I. Barott was an upstate New York native who was educated at Syracuse University and began his career with McKim, Mead, and White in New York City. His client, John E. Aldred, was based in New York though heavily invested in Quebec. To soften the building’s New York accent, the ornamentation included Montreal-themed flora and fauna motifs.

Located on Place d’Armes, a public square in the heart of Old Montreal, those Big Apple inspired setbacks have the desired effect of contextualizing it with its shorter neighbors which include the New York Life Insurance Building (1889) and Notre Dame Basilica (1829).

Left: NY Life Insurance and Aldred Buildings, Notre Dame Basilica; Right: Aldred Facade Detail

The Montreal Botanical Garden Administration Building is an Art Deco tour de force, with balanced composition, radiant brick and stone facades, vertical and horizontal texture, and thematic bas-relief ornamentation. It gracefully complements its beautiful landscaped settings.

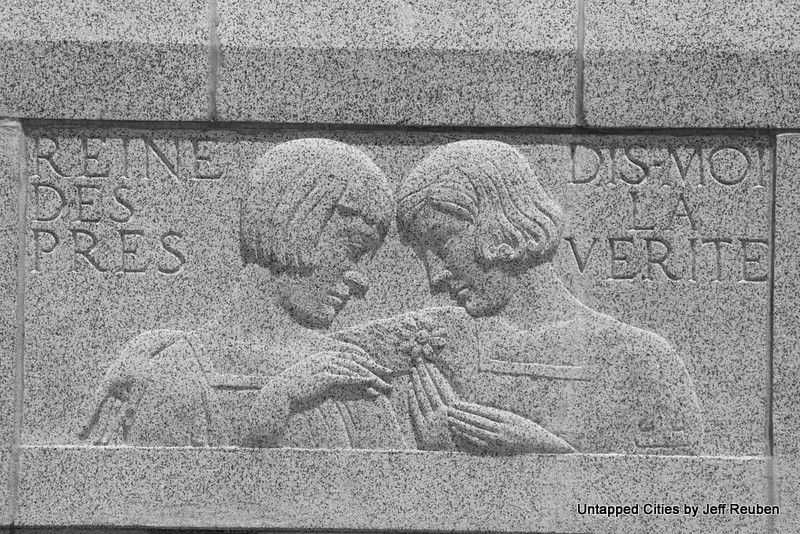

Bas-relief by Henri Hébert

The Montreal Botanical Garden was a triumph of collaboration with the sum being greater than its parts. Its visionary founder, botany professor and Catholic monk Frère Marie-Victorin, secured funding from his former student Mayor Houde and assembled a team to execute his vision.

Bas-reliefs by Joseph Guardo

Lucien Kéroack (Marie-Victorin’s distant cousin) served as lead architect for the central part of the building constructed in 1932 and continued in this role, assisted by Emmanuel-Arthur Doucet, with the brick-faced wings completed in 1939. The bas-relief work was divided between sculptors Joseph Guardo and Henri Hébert. Garden Superintendent Henry Teuscher, a German-born horticulturist and landscape architect who previously worked at the New York Botanical Garden, designed the reception gardens and its water features.

“Queen of the Meadows, Tell Me the Truth”

In recent years, the building and the landscaping have been restored to mint condition.

Pouring maple sap into a barrel

Atwater Market

When the Depression hit Montreal, one of the first public works projects was the construction of three Art Deco public markets.

Marché Atwater

The largest is Atwater Market (1933), measuring about 378 feet long by 60 feet wide plus projecting canopies, with market activities at the ground floor and basement plus a 10,000-seat auditorium topped by a vaulted ceiling in the upper level. Architect Ludger Lemieux, assisted by his son Paul, was known for designing churches and here he included a clock tower, signifying Atwater Market’s importance as a civic building (it also concealed a water tower). Despite some changes and challenges over the years, it remains a popular public market though the auditorium space now houses a gymnastics club.

Atwater Market

Not as big as Atwater, St. Jacques Market (1931) by architects Trudel and Karch also included a tower and a public hall above the market. It features distinctive bas-reliefs including some with food themes. Following years of under utilization, recent alterations include townhouses on the upper level that included a vertical addition (2017) and new ground floor commercial uses, including glass enclosed retail spaces below the exterior canopies (opening late 2019/early 2020).

St. Jacques Market: Entrance and Detail (Note Pineapple Relief)

St. Jacques Market: Fish and Squid Reliefs

St. Jacques Market: Alterations in Progress July 2019

Smaller than the other two is the Jean-Talon Market building, (1933) by Charles A. Reeves, endearingly known as the Chalet. Originally called the Northern or Shamrock Market, it is a well-proportioned Art Deco design with a simple linear character. It continues to serve as the base for Canada’s largest open-air market.

Jean-Talon Market

Police and Fire Station 23

New Art Deco police and fire stations were another part of Montreal’s public works response to the Depression. Ludger Lemieux designed Police and Fire Station 23 (1931), another distinctive building with a tower, which also features reliefs by Joseph Guardo apropos to the building uses.

Police and Fire Station 10

Located close to downtown, Police and Fire Station 10 (1932) by Harold Edgar Shorey and Samuel Douglas Ritchie has a restrained limestone facade. A relief depicts symbols of Montreal: ships, a church dome, and, the pièce de résistance, an Art Deco skyscraper.

Police and Fire Station 48

Emmanuel-Arthur Doucet demonstrated his mastery of brickwork and stone trim, which he later executed on a larger scale at the Montreal Botanical Garden, with Police and Fire Stations 31 and 48 (both 1931) and Police Station 41 (1932). Ironically, the Unemployment Commission occupied Station 48 after its completion and the fire department only moved into its intended area in 1948.

Police and Fire Station 31

Police Station 41

Today, these Art Deco stations are still used by the Fire Department, though the police spaces are now occupied by stores and community organizations.

Police and Fire Station 23 Reliefs

Police and Fire Station 23: Tower

Police and Fire Station 10: Bas-relief

Chateau Theatre Facade

The Chateau Theatre (1932) fuses Art Deco with 1920s movie palace flair (think: New York City’s Wonder Theaters). The work of architect René Charbonneau and sculptor Joseph Guardo, its exterior is ornamented with bas-reliefs, colorful stained glass windows, and a stylized arch.

Chateau Theatre: Bas-reliefs

Chateau Theatre

Chateau Theatre

The Snowdon Theatre (1937) by architect Daniel J. Crighton, built five years later, is all Streamline Moderne. It is massed with vertical volumes and a central ziggurat, but the only facade detailing consists of horizontal stripes, a marquee, and a canopy.

Snowdon Theatre: Reconstruction July 2019

Prolific theater designer Emmanuel Briffa decorated the interiors of both theaters with intricate details beloved by local Deco enthusiasts.

Snowdon Theatre: Reconstruction July 2019

The Snowdon deteriorated due to abandonment and arson. The exterior is being preserved (“facadism“) while a new residential condominium is under construction behind and above it. Thankfully, the Chateau retains many of its original elements and is now used as an event venue and its former balcony is home to Le Château de Cirque, a circus school.

While Prohibition prevailed in the United States, north of the border National Breweries Limited was prospering and constructed a new home office in 1931. Similar to Police and Fire Station 10 by Shorey and Ritchie, with a location close to Downtown Montreal, architect Harold L. Fetherstonhaugh and his client opted for a conservative monochrome stone cladding with subtle vertical and horizontal character.

National Breweries: Brewing Related Reliefs

It also has extensive ornament in the form of bas-reliefs and metalwork above the doors. In a city full of interesting Art Deco detailing, National Breweries has some of the best, with a blend of typical motifs such as octagons and chevrons together with beer related items including hops and their vines, barley, malt, and three mash paddles (a logo used by one of the company’s brands). Being “national,” there are maple leaves too.

It is now an office building and as such not generally open to the public, but reportedly it retains many of its exquisite original details including marble and metal detailing.

Ernest Cormier House

Montreal boasts several notable Art Deco private homes and apartment houses. Among the former are the Ernest Cormier House (1931), designed by its namesake and later inhabited by past and current prime ministers Pierre and Justin Trudeau. It includes a relief of a woman holding a replica of Cormier’s Université de Montréal tower. Another attractive private home is the Simon Kirsh House (1934) by Shorey and Ritchie architects, a suave horizontal work.

Simon Kirsh House

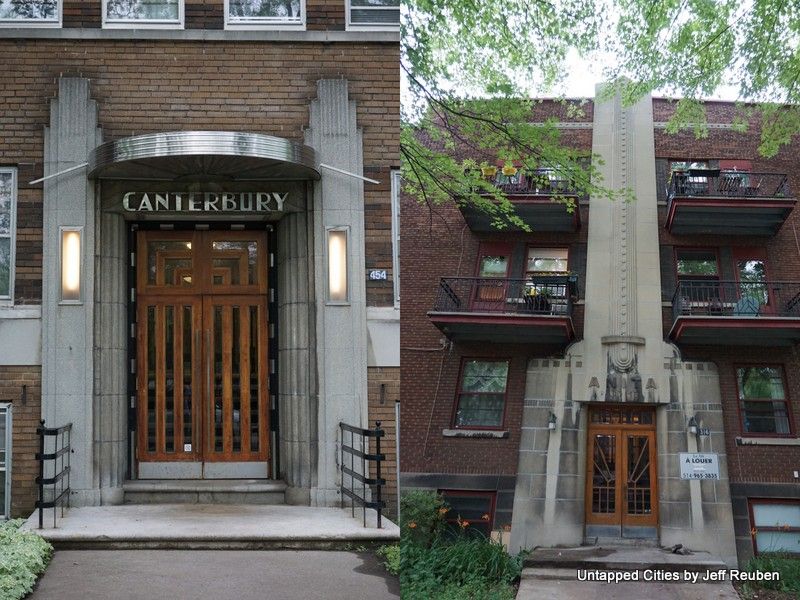

Apartment houses include several on Willowdale Avenue, which form an Art Deco residential district reminiscent of larger ones found along the Bronx’s Grand Concourse and Mexico City’s Avenida Mexico. Buildings there include Modern Court (1938) by Maxwell M. Kalman and two by Brooklyn-born Patsy Colangelo, Anita Apartments (1937) and Canterbury Apartments (1938). Fun fact: Colangelo also had a daughter named Anita.

A not so fun fact: Colangelo was interned for about a month during World War II because one of his other Art Deco works, a cultural center funded by Italian government, Casa d’Italia (1936), included prominent Fascist symbols. After his release, he resumed his practice.

St. Joseph’s Oratory: Basilica

The largest church in Canada, St. Joseph’s Oratory, constructed from the 1910s to 1960s, has an Italian Renaissance exterior, but inside an ecclesiastical variant of Art Deco predominates. Its central basilica, designed in the 1930s by French architect-monk Dom Paul Bellot, features concrete canted arches and an octagonal dome.

St. Joseph’s Oratory: Artwork

Artwork there includes bas-relief Stations of the Cross by French sculptor Roger de Villiers and wooden statues of the 12 Apostles by French artist Henri Charlier with elongated and flattened features, purportedly inspired by the Moai figures of Easter Island. This adaptation fits well with Art Deco’s stylized, linear character.

Chevra Kadisha Synagogue (now Ukrainian National Federation Montreal Branch)

Other examples of sacred Art Deco include two synagogues: Chevra Kadisha (1929), altered by architect J. Melville Miller from a 1907 Romanesque church design, and Beth Moishe (1952), which despite its Modernist building design, has quintessentially Art Deco reliefs of Jewish themes by the ubiquitous Joseph Guardo.

Beth Moishe Synagogue (now Congregation Toldos Yakov Yosef of Skver): Bas-reliefs

Two Catholic schools by architect Eugène Larose stand out for different reasons: brickwork at the Cherrier (1932) and reliefs at Notre Dame de la Defense (1933).

Cherrier School (now Espace-Jeunesse School)

Notre Dame de la Defense School (now La Petite Patrie School): Bas-reliefs

Passing by the Pharmaprix store on Côte des Neiges Road, it can be hard to imagine that the building opened in 1935 as the Canadian Catholic Museum (later renamed Canadian Historical Museum), a wax museum that operated until 1989.

Praised for the “purity of its lines and style” when it opened, it’s been altered substantially since but the impressive exterior works of French sculptor and museum co-founder Albert Chartier remain. These include statues of the New Testament’s Four Evangelists, styled in an Art Deco manner with rippled contours, and an arched frieze of maple leaves at the former main entrance.

Canadian Historical Museum: The Four Evangelists

Architect Paul M. Lemieux employed a modified horizontal Streamline style, with the statues in place of rounded edges. When we visited, a dumpster sat in front one of those statues, its beauty persisting in spite of this indignity. This is an apt metaphor for Montreal Art Deco – though not always respected as it should be, as long as it survives, it continues to shine.

Un trésor caché

Next, read about Mexico City Art Deco gems, top 10 secrets of the NY Botanical Garden, and NYC’s first Art Deco skyacraper: the NY Telephone Building.

Contact the author at @Jeff_Reuben

Subscribe to our newsletter