Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

Image from the Prospect Park Alliance Archives

Image from the Prospect Park Alliance Archives

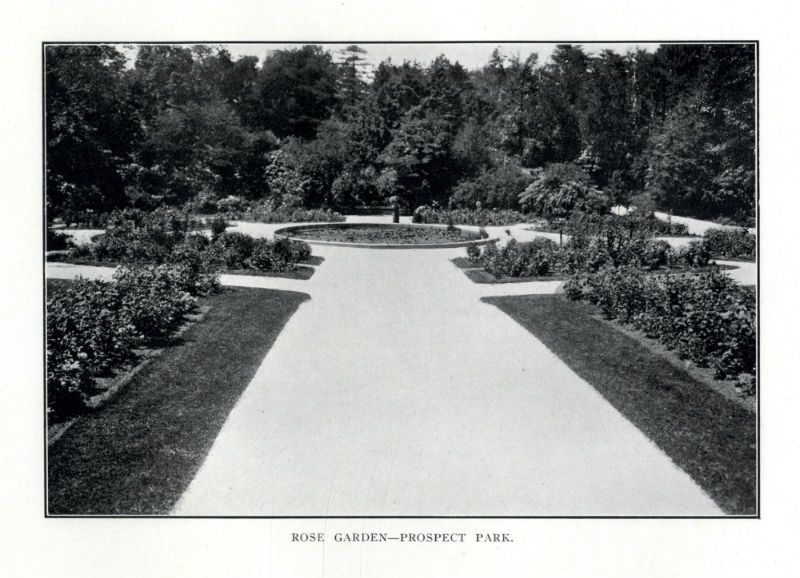

Prospect Park’s Rose Garden — which has not seen a rose in bloom since the 1800s — will soon be full of flowers, except these flowers will be made of pinwheels, which in turn will be made from writing and images expressing love for the park and reflecting on its long history. From July 7 to 17, 7,000 pinwheels will be on display as part of an art installation called the Connective Project, presented by the Prospect Park Alliance in collaboration with AREA4 and Reddymade Architecture + Design. The installation will commemorate the garden’s legacy and will celebrate the launch of its next chapter.

The Rose Garden is a 2.5 acre stretch of woods in the northeast corner of Prospect Park. It has been relatively secluded for a long time, but in celebration of the park’s 150th Anniversary, the space will be transformed. What it will become is currently unknown, but the Prospect Park Alliance and Hester Street Collaborative will be hosting a free community workshop on June 10th in order to kickstart the process of finding out. The workshop encourages any and all interested community members to come together to brainstorm ideas for a complete renovation of the long-flowerless garden.

Prospect Park’s rose garden in its heyday. Image from the Prospect Park Alliance Archives

Prospect Park’s 150th Anniversary celebration has already catalyzed several major projects, including a major opening day weekend festival in May, a New York Philharmonic performance that will occur on June 16th, and the BRIC Celebrate Brooklyn! festival, which will be held at the Prospect Park bandshell throughout the summer, featuring performers such as as Conor Oberst, Fleet Foxes, and Sufjan Stevens.

Image from the Prospect Park Alliance Archives

The Rose Garden as it is today feels removed from these celebrations. It is a peaceful, reflective oasis; a secret, mostly empty field of green that feels simultaneously detached from civilization and haunted by its past. It feels much farther away from the city than it actually is due to the density of the lush woodlands that shelter the area, seemingly separating it from the rest of the world.

It is about a five minute walk away from the park’s Grand Army Plaza entrance. From the plaza, a walk along a shaded path leads to an open grassy area, broken by two gaping cement holes — the remnants of the defunct fountains that were part of a previous effort to reinvigorate the space.

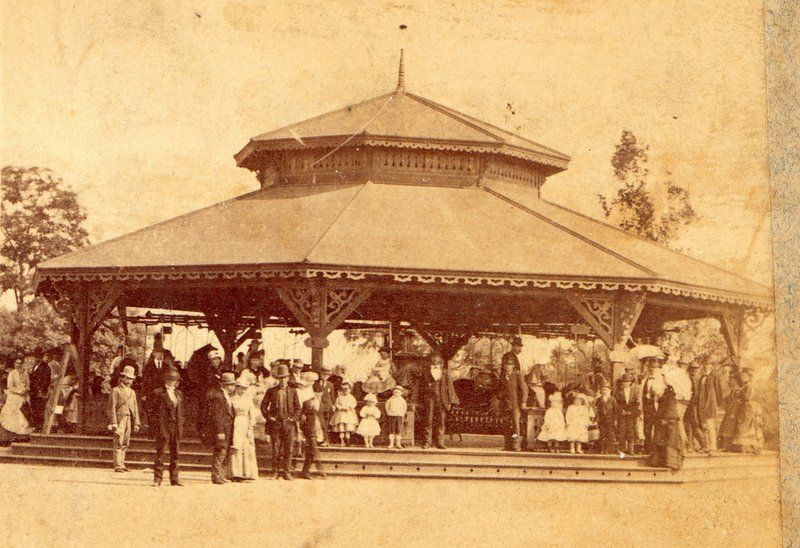

The Rose Garden was not originally created to be a rose garden. The space was first a children’s playground designed by Frederick Law Olmstead and Calvert Vaux, the two principal architects of the park at its inception. In the mid-1800s, when the playground was installed, it had a horse-driven carousel, swings, seesaws, parallel bars, croquet lawns, and a maze, among other attractions. Olmstead and Vaux had designed the park with both picturesque and sublime ideals in mind, and the playground and pools, being part of the picturesque, offered a space where children could play and enjoy nature in the middle of a metropolis.

The carousel at Olmstead and Vaux’s playground. Image from Prospect Park Archives/Herbert Mitchell Collection

During the City Beautiful movement, a major reform movement that implemented large-scale city beautification projects in order to promote harmony and societal cooperation, the actual Rose Garden was installed. In 1885, the firm McKim, Mead, and White, known for their neoclassical architecture, set up a garden full of scarlet roses, complete with three lily ponds.

Images from the Prospect Park Alliance Archives

The skeletons of those ponds are still there today, but they have been empty for many years. As the tumult of modernity took hold and decimated many of the ideals that flourished at the turn of the century, the Rose Garden fell into disrepair. It turned out that the earth was not conductive to growing roses, and the flowers soon died. The ponds soon stopped running as well. They were revived for the centennial in 1966, but that only lasted for a season before the pipes burst in the winter. Since then, for over half a century, the ponds have been bone-dry. Like much of Prospect Park (before the Prospect Park Alliance was founded), the Rose Garden began to come apart at the seams.

The whole park hit a low point in the late 1960s, following Robert Moses‘ modernization efforts, which resulted in a great deal of development that decimated the elegance of the park’s original design. During this time, Prospect Park had very little money, especially after the fiscal crisis in the 1970s.

The entrance to the Rose Garden

In the 1980s, the Prospect Park Alliance was formed, and went to work restoring the park. Still, the Rose Garden remained an afterthought, a relic of the past located far away from the park’s most popular attractions.

Rendering of the Connective Project. Image from the Prospect Park Alliance

Soon, the Rose Garden will enter a brave new era. The Alliance is working with the Hester Street Collaborative, an organization that refurbishes underserved areas, to pump new life into the space. The Connective Project, one of the first movements of the rehabilitation effort, was conceived in partnership with the groups AREA4 and Reddymade Architecture + Design, and it began accepting submissions on June 1st. The project asks for writing, art, and anything else that incorporates images inspired by love for Prospect Park. All of the contributions will be featured on the project’s website, and select pieces will be turned into actual pinwheels.

Rendering of the Connective Project. Image from the Prospect Park Alliance

By the time the Connective Project goes up, plans for the Rose Garden’s future will hopefully be coming together. “We are genuinely asking for input,” said Lucy Gardner, the park’s communications manager. She emphasized the fact that the future of the space is currently a blank slate. “There are so many diverse community groups,” she added, citing the wide variety of suggestions that had already been offered —including one proposal for a laser tag space. What the garden will become is anyone’s guess, and the sky is the limit. It could be anything from a community center to a garden to an arena, depending on what the participants at the brainstorming session believe is best.

Bird’s eye view rendering of the Connective Project. Image from the Prospect Park Alliance

“We hope this will draw tons of people to a space they didn’t know about,” she said, adding that there will be a Spanish-speaking moderator at the event. The designers hope to take in as many different perspectives as they can, in hopes that the space will work as an asset for the entire community.

One of the sunken ponds from the McKim, Mead, and White days

As it is, the Rose Garden is still meaningful to certain groups of people. For example, in the 1970s and 80s, the nearby Vale of Cashmere — a secluded area separated from the garden by a thicket of trees — was a meeting place for many gay men and others who were not accepted or comfortable in mainstream society. In their secret, overgrown states, these places have acted as portals to other worlds for certain subsets and groups of people. A recent book by Thomas Roma

showcases careful black-and-white photographs of some of the people who found refuge and release there.

The Vale of Cashmere got its name from a Thomas Moore poem that reads: “Who has not heard of the Vale of Cashmere?/With its roses the brightest that Earth ever gave/Its temples, and grottos, and fountains as clear/As the love-lighted eyes that hung over their wave?”

There are many other rehabilitation projects going on all around the park. Much of the Vale of Cashmere was decimated by Hurricane Sandy, and this has resulted in an influx of invasive species taking over the previously healthy forest floors. For the second year in a row, the park has brought in a team of goats, who dutifully devour the invasive species while leaving the native ones alone. The goats, named Max, Unicorn, Cinnamon, and Swirl, are playing their part in preserving Brooklyn’s last remaining forest.

Goats rehabilitating the Vale of Cashmere

Max, a goat so talented he has returned for a second year in a row

For now, in its raw state, the Rose Garden is worth a visit. The sunken ponds feel nostalgic and unassumingly beautiful in the way abandoned things or manmade places reclaimed by nature can be. For urban explorers and history buffs, the area is an intriguing capsule of times past.

The tall forests surrounding the empty ponds are broken by winding paths, which seem to beckon the observer into a world of mystery just beyond the threshold of the trees. The whole place has a down-the-rabbit-hole, Narnia-type of feel to it. It has been reclaimed by nature and by wilder sectors of humanity, and while the restoration will open up the space to new groups of people, certainly something will be lost when the area is developed.

What exactly that future will entail remains a mystery, too, but soon enough the Rose Garden will begin the process of entering a new era, cheered on by all the fanfare that spinning pinwheels can provide.

Next, check out 10 Lost or Never Built Structures in Brooklyn’s Prospect Park and the 2000-headstone Quaker Cemetery in Prospect Park.

Subscribe to our newsletter