Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

May 10th marks the 175th anniversary of the Astor Place Opera House Riot, one of the most deadly riots in New York City history, in 1849.

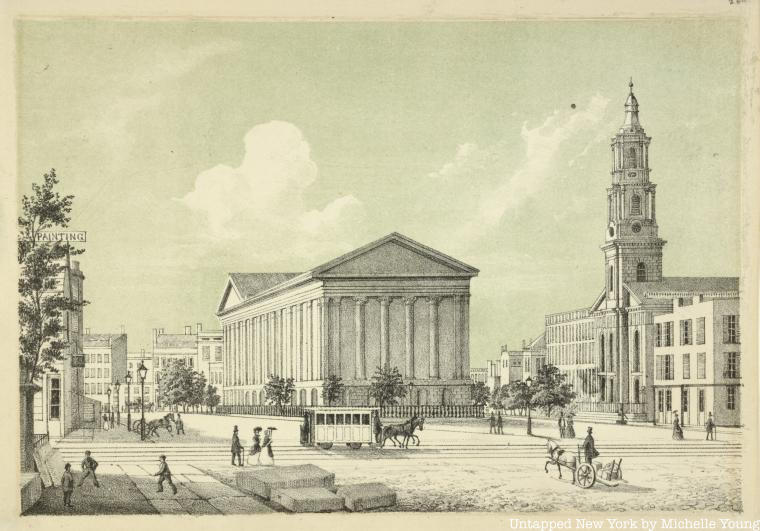

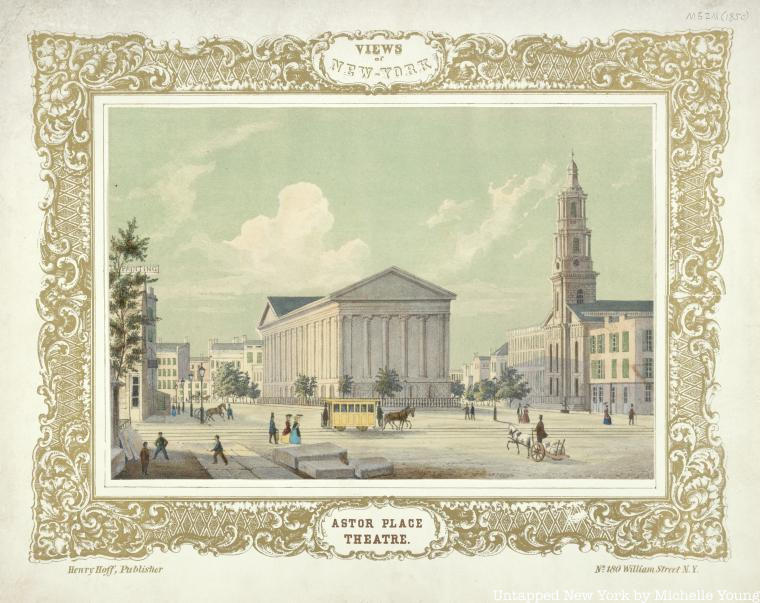

May 10th marks the 175th anniversary of the Astor Place Opera House Riot, one of the most deadly riots in New York City history. The Astor Place Opera House was the first of the big purpose-built opera houses in New York City and one of the most famous (and infamous) of the city’s lost opera houses. As its name suggests, it was located at Astor Place, on the wedge of land bounded by Lafayette Street, East 8th Street, and St. Mark’s Place. The Astor Place Opera House was conceived by a man by the name of Edward Frey, an impresario who managed the opera house during its entire, short-lived history. Listen to our podcast episode on the lost opera houses of New York City to learn more, or read on!

The Astor Place Opera House debuted on November 22, 1847 with a performance of Giuseppe Verdi’s Ernani, which was very well-received and very well-reviewed. Later on, the Astor Place Opera House debuted Verdi’s Nobuko in 1848. Verdi’s operas, and five other operas will have their American debuts at the Astor Place Opera House.

The Astor Place Opera House could fit an audience of 1,100 people and had a traditional opera seating arrangement. There was a dress circle and a first tier, and a gallery for 700 people. As The New York Tribune pronounced, “Opera must have an elegant environment if it is to succeed.,” and so the Astor Place Opera House did. The interior was lavish—overly ornate with gigantic chandeliers, moldings all over the many rungs of horseshoe-shaped tiers. The opera house also hosted balls and masquerades and went out of its way to cater to the wealthy New Yorkers. It was located further north than other entertainment venues were built, but right where all of the rich families of New York relocated to in the 1840s.

The Astor Place Opera House ushered in a new era of attending opera for the purpose of people watching—it was a place to see and be seen—which later comes to a head in the future opera house wars which was fictionalized quite accurately in the second season of The Gilded Age (our podcast episode features clips from The Gilded Age, courtesy HBO). The Astor Place Opera House had a very strict dress court code: everybody had to have freshly shaven faces for men, evening dress, and kid gloves. You had to look a certain way to get into the Astor Place Opera House.

The Astor Place Opera House was also the first opera house in New York to run on subscription, meaning that the well-heeled of New York could buy subscription seats, or become members of the opera for a very high price, equivalent to about $1,000 in today’s dollars. In return, they would get their own box at the opera house. Conversely, even first and second-tier seats were out of range of the working and immigrant classes of New York at the time, at about $25 to $30 a seat in today’s money—a lot of money for people at that time. There was also a very large open general admission area, which was more accessible by price range, but not by location, as you had to take a very narrow staircase to get up there.

This divide between the haves and have-nots was the root of the Astor Place Opera House’s problems, all of which come to a head in the spring of 1849. At this time, when people wanted to let their discontent be heard, they went to the theater. If they didn’t like what you were doing, they would hiss, boo, and yell, and throw things including food. The Astor Place Opera House didn’t want this kind of behavior inside, and because of that, it drew a lot of attention.

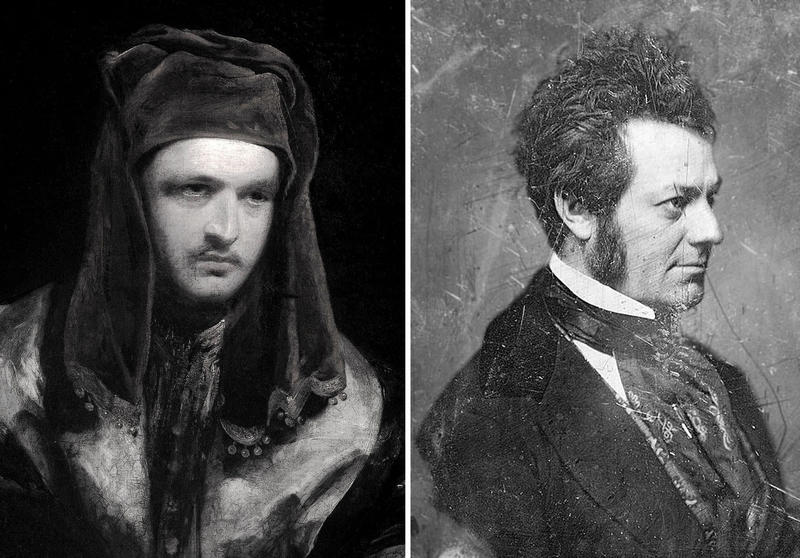

At a time of high tension between the social classes in America, two theater actors were booked on the same night to play Shakespeare’s Macbeth: American actor Edwin Forrest and English actor William Macready. The dispute was a microcosm of what was going on with the social classes—the affluent upper tens aligned with Macready and went to see him perform Shakespeare proclaiming that he was the actor who could do Macbeth justice in the British theater tradition. The working classes were forging themselves as new Americans and championed Edward Forrest. Posters were put up all around the city stating, “Working men! Shall Americans or English rule the city?” They feared what was termed, a new English aristocracy.

The first protest was the night of May 7. The working classes got outfitted properly and paid $1 to gather in the general area. They hissed and booed Macready, yelling “Shame! Shame!” and threw rotten eggs, to the point that Macready walked off stage and said he was leaving. Herman Melville, and a few other famous, well-heeled artists convinced Macready to stay and finish his performance. Meanwhile at the same time, down at the Broadway theater, Edwin Forrest was playing Macbeth to a sold out, thunderous crowd who applauded him the whole time,

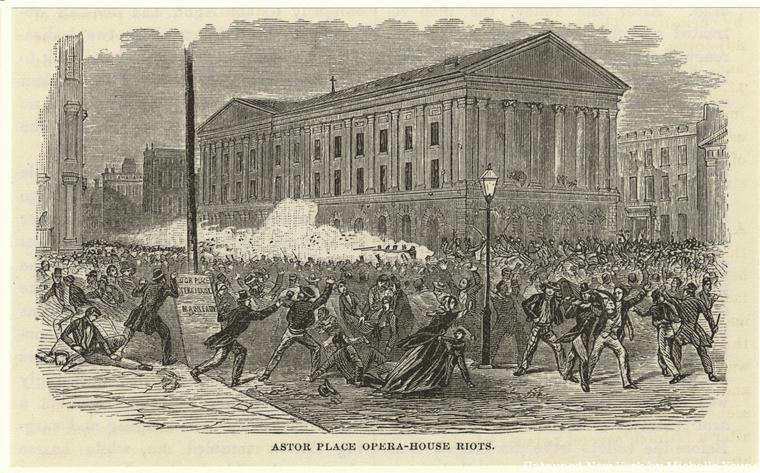

Working-class New Yorkers were encouraged to come and protest at the Astor Place Opera House a few days after the first doubleheader. 10,000 people filled the streets around the opera house, none of whom were ready to protest peacefully. With the rallying cry of “Down with the codfish aristocracy!”, they brought rocks and bottles to use as projectiles at audience members and anybody trying to stop them. The opera ‘houses’ guests were pre-screened that evening and anybody carrying items in their pockets were not allowed inside. But that night, the threat did not come from the inside—it was on the outside.

The New York City Police Department knew right away that they were not going to be able to handle the riot, so the New York State militia was brought in. At first, they formed a line and shot their guns straight into the air without injuring anybody. But then without warning, they turned on the participants and started firing. There were casualties on all sides, including police, militia, and innocent bystanders. It was said somewhere between 22 and 31 rioters were killed that evening, and 48 were wounded. Somewhere between 50 to 70 policemen were injured. 141 of the militia were injured, mainly by rocks and bottles being thrown at them. Macready. managed to sneak out of the theater in disguise.

Incredibly, the demise of the Astor House Opera House came not at the hands of Shakespeare, but by monkeys! Listen to our podcast episode below on lost opera houses to learn more about its fate. Today, the Astor Place Opera House is no more, but the site which it stood on still exists in Astor Place.

Next, check out The Lost Opera House of NYC

Subscribe to our newsletter