Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

View of Barcelona from Museu National d’Art de Catalunya (MNAC)

View of Barcelona from Museu National d’Art de Catalunya (MNAC)

Great cities often have prickly relations with their national governments — witness New York City’s move to become the 51st state in the 1970s — but seldom has a city gone as far as Barcelona. Gorgeous, wealthy, and contentious, Barcelona is the capital of Catalan separatism, a centuries-old movement that came to a head in a December 21st election imposed by Madrid.

Like New York City, Barcelona sends far more money in taxation to the national government than it receives back in resources and services. And, like New York, its culture, sophistication, and welcoming attitude towards migrants have often been at odds with the rest of its country. But it also has its own unique grievances, stemming from the central government’s attempted suppression of Catalan culture, including the language, as “part of the general, repressive attitude on the part of the government early in the 19th century,” writes independent scholar Marilyn McCully in Homage to Barcelona: The City and its Art. The extraordinary cultural flowering that was termed “Catalanismo” from 1880 to the end of World War I produced the renaissance of “La Renaixença,” unmatched anywhere in Spain, or perhaps the world.

And while it is far from clear how many Barcelonés supported independence before the October 1 election that Madrid pronounced illegal, it is clear that the violence of the Spanish national police blocking and beating voters propelled many into the separatist coalition. Perhaps most incomprehensibly to Americans, the most prominent separatist leaders have been imprisoned for rebellion and sedition by Madrid, or have fled into exile. Yet all over, Barcelona Catalonian flags fly and posters supporting Carles Puigdemont, the president of Catalonia who was fired by Madrid, get taken down by the police, only to quickly reappear.

Catalan flags on historic buildings, Passeig de Gràcia, in the elegant Eixample quarter

Catalan flags on historic buildings, Passeig de Gràcia, in the elegant Eixample quarter

As the ferociously anti-independence writer Javier Cercas, who calls himself a leftist Europeanist, wrote in the New York Times, “Since Spain became democratic, the Catalan government has had exclusive control over vital matters like education, language, culture and public works.” Catalonia, he argues, has been basically in charge of its own fate, often heading in an entirely different direction from the rest of Spain, which fairly tolerantly accepted the differences. The Parliament of Catalonia, for example, banned bullfighting events in 2010, effectively shutting down Barcelona’s famous bullring, La Monumental, now a shopping mall called Arenas de Barcelona. Bullfighting continues in the rest of Spain, which regards it as a fundamental part of its heritage. Catalonia pretty much stands alone.

Plaza de Toros de las Arenas, now a shopping center called Arenas de Barcelona, was Catalonia’s last bullring.

Plaza de Toros de las Arenas, now a shopping center called Arenas de Barcelona, was Catalonia’s last bullring.

F.C. Barcelona, one of the world’s greatest soccer clubs, is a global institution with 300 million followers on social media. So fundamental is Catalonia to the soccer club’s identity, its stadium signs are primarily written in Catalan.

And, of course, no one but Barcelona has Antoni Gaudí, although many imitators abound. Gaudí’s wild, exuberant, brilliantly engineered neo-Gothic structures inspired by Catalan traditions stop people dead in their tracks all over the city.

Antoni Gaudí’s Sagrada Família, begun in 1882, is the largest Catholic church under construction in the world.

Antoni Gaudí’s Sagrada Família, begun in 1882, is the largest Catholic church under construction in the world.

Gaudí called Sagrada Família a temple, not a church, but when finished, it will be the world’s tallest religious building.

Gaudí called Sagrada Família a temple, not a church, but when finished, it will be the world’s tallest religious building.

Japanese sculptor Etsuro Sotoo’s Door of the Charity at the Nativity Facade of the Sagrada Família

Japanese sculptor Etsuro Sotoo’s Door of the Charity at the Nativity Facade of the Sagrada Família

Gaudí’s first house, Casa Vicens, Carrer de Los Carolines

Gaudí’s first house, Casa Vicens, Carrer de Los Carolines

Gaudi’s Casa Milá (La Pedrera) displays his contempt for straight lines, adhering to zoning requiring a chamfered corner.

Gaudi’s Casa Milá (La Pedrera) displays his contempt for straight lines, adhering to zoning requiring a chamfered corner.

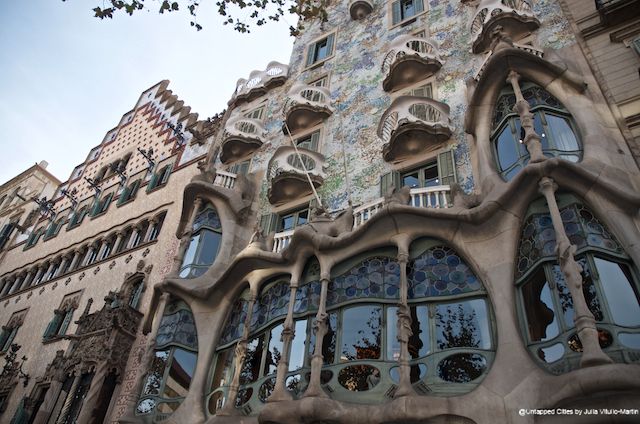

Block (or Apple) of Discord, Manzana de la Discòrdia, Casa Amatller by Josep Puig, left, and Casa Batlló by Gaudi, right

Block (or Apple) of Discord, Manzana de la Discòrdia, Casa Amatller by Josep Puig, left, and Casa Batlló by Gaudi, right

Devoted both to what he called the Great Book of Nature and to Catholicism, Gaudí attracted many opponents for his unusual views and an equal number of opponents for his extraordinary decoration. During the Spanish Civil War anarchists rampaged through Sagrada, destroying the models and plans that had been carefully preserved in archives after his death in 1926. Sagrada’s construction workers prevented the anarchists from opening Gaudí’s tomb or bombing the structure, but the destruction of the plans has forced today’s architects to improvise in ways that may well deviate from Gaudí’s intentions. (The Civil War vandalism was approved by George Orwell, who characterized Sagrada as “one of the most hideous buildings in the world.” America’s Louis Sullivan, on the other hand, had called it “spirit symbolized in stone.”)

After the fall of Franco, the mayor of Barcelona wanted a progressive city. He agreed to demolish the front section of Josep Puig’s magnificent Casa Serra in order to build a modernist structure to house the regional government (below). The result, which is pretty bad, could have been worse.

Josep Puig’s Casa Serra, 1908, modified to accommodate the regional government’s Diputació de Barcelona

Josep Puig’s Casa Serra, 1908, modified to accommodate the regional government’s Diputació de Barcelona

Barcelonés can be quick to explain that their centuries of ignoring the waterfront were historic. Even though Columbus brought his ships to Barcelona in 1493, the 1479 merger of Catalonia with Castile had not benefited Barcelona economically. Instead, Catalonia was deliberately isolated and, in 1521, forbidden to trade with the New World, eradicating its role as the largest Mediterranean port. Rebellions followed, but Catalonia lost its independence in 1714. Barcelonés today bring up this history in discussing the contemporary success of the waterfront, rejuvenated by the Olympics of 1992.

Head office of Port Authority of Barcelona being lovingly restored

Head office of Port Authority of Barcelona being lovingly restored

Barcelona waterfront separates pedestrians from cars, encouraging walkability.

Barcelona waterfront separates pedestrians from cars, encouraging walkability.

Bikes are readily available on the Barcelona waterfront, which offers fine paths.

Bikes are readily available on the Barcelona waterfront, which offers fine paths.

Visitors can figure out how to get where they’re going easily, thanks to public transpo information.

Visitors can figure out how to get where they’re going easily, thanks to public transpo information.

Barcelona combines good city planning bones with gorgeous nature.

Barcelona combines good city planning bones with gorgeous nature.

Barcelona has survived wars, armed rebellions, and immense injustices from national regimes. It will survive this election. Angry as the writer Javier Cercas is about the separatist movement, he probably has it right when he says, “Being Spanish means to me: a peculiar way of being European.” Indeed peculiar in all sorts of wonderful ways, Barcelona has also long been seen as the most European of Spanish cities. Therein lies its future.

Julia Vitullo-Martin is a Senior Fellow at the Regional Plan Association. Get in touch with her @JuliaManhattan.

Subscribe to our newsletter