Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

By the end of this year, the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center is set to complete a $9 million renovation at its West 13th Street home, which includes an update to aging technologies. Robert Woodworth, the Center’s director of capital projects, gave us a behind-the-scenes look at its progress, just in time for the 45th anniversary of Stonewall. Woodworth has been with the Center since the very beginning, and was eager to share his insight into its past, present, and future.

Long before the Center existed, the building was a three-story grade school, constructed in 1844, which underwent several expansions in the 1800s. Wings were added, and in the 1890s, a “playshed”—a covered outdoor play space—was erected on the northwest corner of the site. Today the playshed houses the Center’s adult wellness and recovery services.

In the 1970s, the building’s future was uncertain, as it couldn’t survive as a school. But the city didn’t want it to be torn down or turned into condos.

In late 1982 or early 1983—soon after the news spread of a “gay cancer”—the city declared its intention to auction the building to a nonprofit.Since the Stonewall riots in 1969, the AIDS crisis was the biggest catalyst for gay activism. At stake was not only a strange new epidemic that was claiming thousands of lives, but the need to get people to start talking about homosexuality not as a sickness or an abomination, but as a fact of life, an identity that in certain ways defines a small, marginalized group, a group that would have to prove itself worth saving.

But it would rarely do so in harmony. Clashing philosophies between—and even within—early gay and AIDS-related organizations is well-depicted in the 2012 documentary How to Survive a Plague. And the Center is featured prominently as the venue of every important lecture, meeting, vote and shouting match in the film. It appears small, poorly-lit and scrappy. But it would become a wellspring of AIDS research and activism in New York City, and indeed the world.

Not only did the health crisis spur people to start talking, it spurred them to give. In April 1983, Gay Men’s Health Crisis staged a performance at the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey circus at Madison Square Garden to raise money for AIDS recovery services. As many as 15,000 people attended, including Mayor Ed Koch, in what GMHC would call the “biggest gay event of all time.” That same year, the Lesbian and Gay Community Services Center was incorporated, and it acquired the building at 208 West 13th Street for $1.5 million.

But not before a struggle with Mayor Koch, who, like President Ronald Reagan, is remembered in the LGBT community as an AIDS denier. (Unlike Reagan, Koch was and continues to be suspected a closeted gay man himself.)

In the 1980s, the Center was the only safe space in New York City that had the words ‘gay’ and ‘lesbian’ in it. Even gay organizations were wary of those words, for fear they would be denied funding or even recognition from the state. But the Center got its first state grant in 1988, for an alcohol services program. Today the Center operates substance abuse treatment, HIV/AIDS support, career planning, family services, lectures, performances, and art shows.

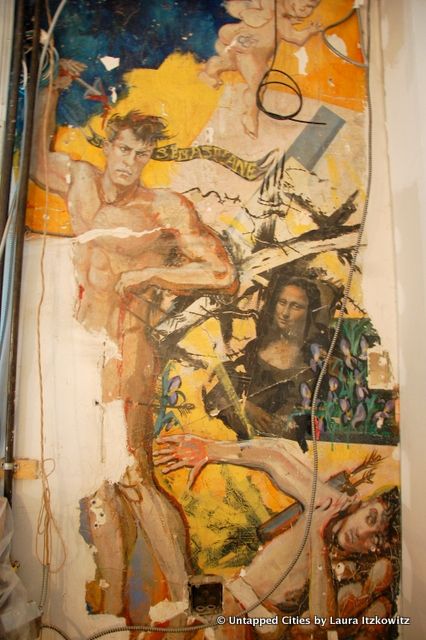

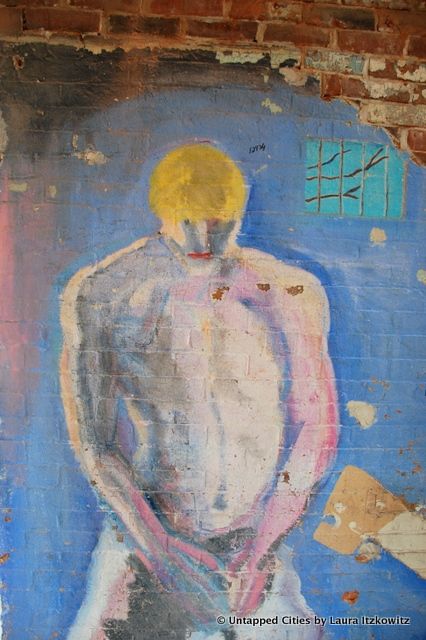

In 1988, the Center began planning an art installation program to honor the 20th anniversary of the Stonewall riots. Organizers invited 50 artists—half men, half women—to choose any location in the building for a site-specific Stonewall memorial piece. The Center is proud that it enabled some artists to show work that they mightn’t have been able to show elsewhere, either because they were gay or because their content was “too gay.”

Of the pieces that remain, the most beloved by far is a 360-degree Keith Haring mural in the former second floor men’s room. Completed just months before his death by complications from AIDS, the mural is a dedication to the pre-1981 days of freewheeling sex. Haring rarely titled his pieces, but he called this one “Once Upon a Time.” The restroom has been converted to a conference room and the mural won’t be visible again until the renovation is complete later this year.

The updated LGBT Community Center will open to a Greenwich Village and a gay landscape that are vastly different from those that laid the groundwork for its inception in the 1980s. Around the corner, condos will replace the historic complex that housed St. Vincent’s Hospital, the locus of early AIDS care and outreach and among the first hospitals in the world to acknowledge the disease, before it closed in 2010. The heartbeat of gay New York has migrated north to Chelsea, then Hell’s Kitchen, then sort of scattered, helped by hook-up apps and increased perceptions of security.

But that is not to say the value of the Center is in any way outdated. While treatment for AIDS has improved, it remains incurable, stigmatizing, and actually increasing among certain populations, among them young black men. And while the legality and acceptance of same-sex marriage seems to be increasing exponentially, many gay New Yorkers face persistent discrimination, especially in poor neighborhoods far from Greenwich Village. The overhaul will add a fresh face and strong bones to an institution with humble roots, whose mission has not wavered, but whose scope has expanded far beyond the Village.

Subscribe to our newsletter