After-Hours Tour of the Fraunces Tavern Museum: "Path to Liberty"

Explore a new exhibit inside the oldest building in Manhattan, a witness to history throughout the Revolutionary War Era!

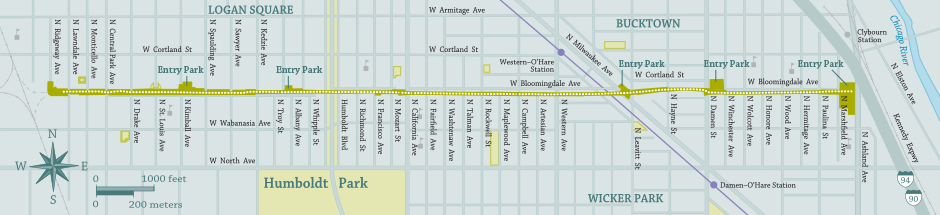

You can get a glimpse of the Bloomingdale Trail, an abandoned railroad line in Chicago, on a Blue Line Train from O’Hare to the Loop. The Blue Line comes in to the city at an angle, and so you’ll only able to observe the verdant path for a few seconds before it disappears behind passing buildings. In a year though, if all goes according to plan, the trail will be open and accessible to the public. This month, The Trust for Public Land helped us get access to the trail to share this story with Untapped Cities readers.

Though it will undoubtedly be compared to New York City’s High Line, it’ll be different. The Bloomingdale Trail is nearly twice the length of the High Line at 2.7 miles, and it cuts through very diverse neighborhoods. Rather than act as a catalyst for development, the Trail will be more about adding green space in already developed but underserved neighborhoods. It’ll be less “designed” than New York’s, retaining a lot of the current elements–the natural growth acting as water filters, the infrastructure pieces rehabbed. And unlike the High Line’s phased construction, the Bloomingdale will be converted in one shot, with incremental additions happening afterwards.

The Bloomingdale Trail was a former freight rail line created in 1873 by the Chicago and Pacific Railroad company along what was Bloomingdale Avenue. Originally at grade, the project owners were forced by the City to elevate the track in 1910 in order to prevent pedestrian deaths, which were occurring frequently. Like many rail lines in Chicago, the line fell in to disuse as the neighborhoods of Humbolt and Logan Square switched from industrial to residential. The final freight train to use the line was in 2001. (An extensive history can be read by our friends at Forgotten Chicago).

Our guide on the trail was Richard Kinczyk, Manager of Design and Construction on the rail-to-trail conversion and a 30-year veteran of Chicago city government. Richard spent part of his childhood not far from the Bloomingdale in Bucktown. As a Chicago municipal employee he rose from staff geologist to First Deputy Transportation Commissioner. Although retired, he takes time to work for the Trust for Public Land, and has personal interest (as well as expertise) to see this project succeed.

We met at the corner of Milwaukee Avenue and Leavitt where a new park is being built. This project is one of five access points to the trail that will also contain a new ground-level, neighborhood park

Kinczyk explained, “One of the main goals of this project is to increase public parkland in these neighborhoods, so these access parks will have great amenities in addition to the trail.” The Trust for Public Land is taking a lead on funding the trail and the access to these parks.

Besides physically integrating this structure back in to the city landscape, it must also be appropriately absorbed by the city agencies that will be responsible for the trail’s new purpose. The land had to be bought by the government, a city agency had to take the lead on design and construction, and a local conservancy had to be created to fund maintenance once the project is finished. The Park District will get jurisdiction of the trail and access-parks, while the Department of Transportation will oversee the viaducts and street crosses. This process can be very tricky, but Chicago has taken lessons learned to push forward at a solid pace.

While standing under the viaduct at Milwaukee Avenue, Kinczyk discussed Chicago’s approach to converting the rail line to a park, “Rather than fully rehab the deteriorating structure, we are going to focus on stabilizing it, which will save a lot of money. For sections like this, we will just remove the loose stuff so there isn’t a hazard.” Since the original structure was meant to carry 80-ton freight trains, the load on top as a park will be much less than the structure’s ability to bear.

The 38 viaducts on the Bloomingdale Trail were built at a time when cars and trucks were much smaller, so much of the renovation will help improve the crossing at these locations. This particular viaduct will be raised, with unnecessary columns removed to avoid trucks from hitting it.

The top of the trail is 20 feet above Chicago’s grid and where the bulk of the work will be undertaken to transform the trail into a park. The initial construction will require the removal of all 3.1 miles of track, which will be recycled by the railroad company. After, they will import 27,500 square yards of 8″ concrete mixed use path, 75,000 cubic yards of planting soil and 25,000 feet (4.73 miles) of pedestrian handrail.

Unique to the Bloomingdale conversion is that a lot of the earth on the trail is going to stay. “The embankment soil is beach sand with a railroad ballast cap on top. The ballast will be reused to create aggregate paths. The sand is a natural filter so water that has been draining through it for the last hundred years or so has been filtered.” Although the tracks won’t stay, the sand will.

Along the way we ran in to Beth White, Deputy Director of the Trust for Public Land, who was leading a tour for artists to explore the structure. “You’re all trespassing!” Kinczyk yelled out to them. After getting a chuckle from the tour, he quietly explained that seeking out artists to participate in the project has been a priority since the beginning for innovative ideas. The Bloomingdale Trail is very straight, so public spaces and art installations will help break up the linear feeling.

At the end of the trail, an old bridge connects to a part of the line that was dismantled some time ago. This bridge will be removed to create an access point, but will hopefully be transferred and reused on another section. Here, Mr. Kincyzk explained one unique design that he was most excited about. Once native plants are installed, there will be a five-day difference in the blooming period east to west. Visitors traveling from one side to the other will be able to see process of nature by simply traversing the Bloomingdale Trail. It will also provide a learning opportunity for local schools to have outdoor classrooms.

Construction is expected to start at the end of the summer, after that Mr. Kinczyk says it will take a year to get the Bloomingdale open and accessible with a bike and walking path. (During the writing of this article the City awarded the first contract). Of course, obstacles are expected that could push this timeline back (you have heard of Chicago’s winters, right?) but Mr. Kinczyk and the other project members are excited about the ambitious timeline. “We want to get the park open, and we expect increased support and funding for more amenities after that.”

On our way back, a jogger passed us by. He was techincally trespassing but that didn’t bother Mr. Kincyzk. His goal is to get people here. He simply smiled and we kept walking on.

Subscribe to our newsletter