Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

Amidst (or due to) the controversy regarding the horse and carriage industry in Central Park, we decided to take a trip to the Clinton Park Stables on W. 52nd Street with Christina Hansen of the Horse and Carriage Association of New York City. The purpose of this article is to show the history of the industry and the workings of this particular stable without getting too embroiled in the hot-topic issue. That being said, it seems that everyone has weighed in on New York City mayor Bill de Blasio’s proposal to ban the carriage horses that will go in front of city council soon.

Liam Neeson has even come out in support of the industry: “I think it’s about real estate. I’m not the kind of person to use my celebrity…but the horses are happy,” he tells NYPost. The pro-horse lobby organization, The Cavalry Group, has come out to say that the bill is the work of “animal extremists” with a “vegan agenda.” In response, NYCLASS (New Yorkers for Clean, Livable, and Safe Streets) has criticized the carriage industry for joining forces with The Cavalry Group, calling them right wing and a “group of zealots.” Meanwhile, taking a different tactic, The Catholic League says that de Blasio cares more about horses than humans.

“Lots of cities have carriages, but nobody really has carriages like New York,” Hansen says to us. “We’re basically cab drivers that didn’t motorize.” Indeed, the license plates on carriages read: “HORSE DRAWN CAB.” The horse and carriage industry received their medallions in 1935 under Fiorello LaGuardia in a large-scale regulation of transportation, but they’ve been licensed by the city since the 1850s.

The well-known horse carriage zone on Central Park South from 5th Avenue to 8th Avenue was designated “Cab Stand #16” in the late 1850s. As testament to the importance of the carriage cabs then, this designation took place before the park was completed. “They had barely hired Olmstead. They were figuring out what to do with the land…but they knew that there needed to be a place for cabs to park,” says Christina.

The cutout of the plaza on 5th Avenue where the General Sherman statue is now was originally a deliberate open area for carriages to park and be out of the way of traffic on 59th Street and 5th Avenue. According to Hansen, even the roads of Central Park took into account carriage driving–not only the speed of travel but also, for example, the views from the back of a carriage.

Hansen believes that the current controversy is part of a cyclical trend and cites similar concerns that arose in the press during the 1920s and 30s, with the arrival of the motorized car. World War II put the horse and carriage industry back into play as gasoline shortages hit the nation. (de Blasio’s alternative to carriages are electric vintage cars).

There are four stables in New York City for carriage horses. Clinton Park Stables is the largest. It hosts 39 carriages and 78 horses, between 35 owners. There are 68 carriages all together in New York City, so Clinton Park Stables has more than half. The number of total medallions hasn’t changed since Mayor Bill O’Dwyer set that number in World War II, who had given medallions to his carriage driver friends. Today, medallions are often passed down within families.

The four stables that the Central Park carriage horses live in were all built as stables, and are all currently owned by carriage people. Clinton Park Stables was built in the 1880s for the city’s sanitation department horses that pulled the street sweepers. For a period, it served as storage for a cardboard box company, but in 2003 it was bought by a co-op of fifteen carriage owners.

Unlike other cities, the New York City carriage industry is run by a collective of individual owners with medallions, rather than by carriage companies that own a fleet of carriages. Even the stables, though privately-owned, are run by a co-op of medallion owners. Though not all the drivers own the stable itself, they pay dues to the co-op.

On the first floor, one half houses the carriages. The grain for the horses is delivered by the ton from a feed mill in Pennsylvania. The stablemen feed the horses hay, but the drivers are responsible for feeding grain to their own horses.

The freight elevator was put in after the building was built. It’s not for horses but for the hay and grain:

When carriages work at night, lights are needed and the generators are charged in this battery room on the first floor:

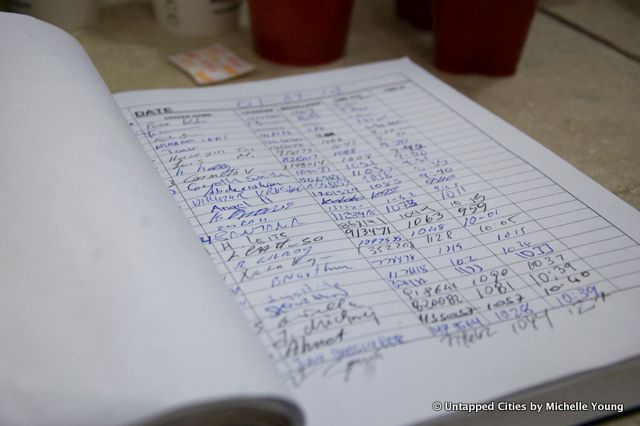

In the driver’s office in the building, time sheets are kept as required by New York administrate code and the laws of New York City:

Old school time punch for the trip card that’s taken with the drivers:

The ramp to the horses’ quarters, in place for over a century with rubber mats so the horses don’t slip:

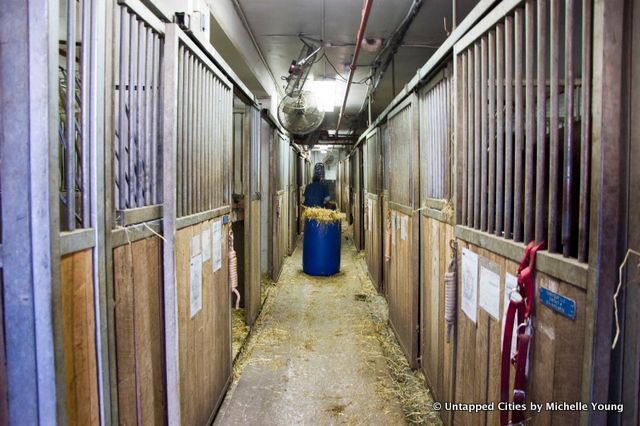

All the stables in New York City are run 24 hours a day. The Clinton Park Stables has a minimum of three staff present here 24/7, says Hansen, and mucking takes place every few hours.

Rosie peeks at us from her stall, having just returned from her required five week per year vacation on a farm in Pennsylvania.

The fans have a misting system used in the summer on very hot days, as horses can’t be air conditioned. The building is also fire-proofed and has automatic sprinkler systems.

The box stalls in Clinton Park Stables are at least 8×10 feet, larger than the city requirement of 60 square feet. Many are quite larger than 8×10, like Rosie’s. The fountains (automatic waterers) in each stall turn on automatically when the horse puts his nose in the sink:

Though no longer used, you can still see the original drainage groove of the stables:

The horses are bedded on straw, but other stables in New York City use shavings:

All the old bedding and manure gets sent to a mushroom farmer in New Jersey:

The manure room, which surprisingly doesn’t smell too bad:

Since the building was originally built as a stable, there are windows on all sides of the building:

Each horse has their respective paperwork on the door of their stall, which includes the license, rabies certificate, immunizations and latest veterinarian inspection:

A wash stall (horse shower) with hot and cold running water:

An old anvil:

As for Christina Hansen herself, she’s a long-time horse rider and enthusiast from Kentucky. She was pursuing a graduate degree in history at the University of North Carolina when her she and her husband relocated to Pennsylvania for his graduate degree at UPenn. She was looking for jobs with tour companies and ended up with the carriage company in Philadelphia, and then moved to New York City. She doesn’t own a medallion but drives for medallion owners here in New York City.

The public can attend tours for the stables through the organization Clip Clop.

Get in touch with the author @untappedmich.

Subscribe to our newsletter