Artist-Led Tour of "ENCORE" Photo Exhibit w/ Mark S. Kornbluth

Join photographer Mark S. Kornbluth for a visual exploration of NYC's Broadway theaters at Cavalier Galleries!

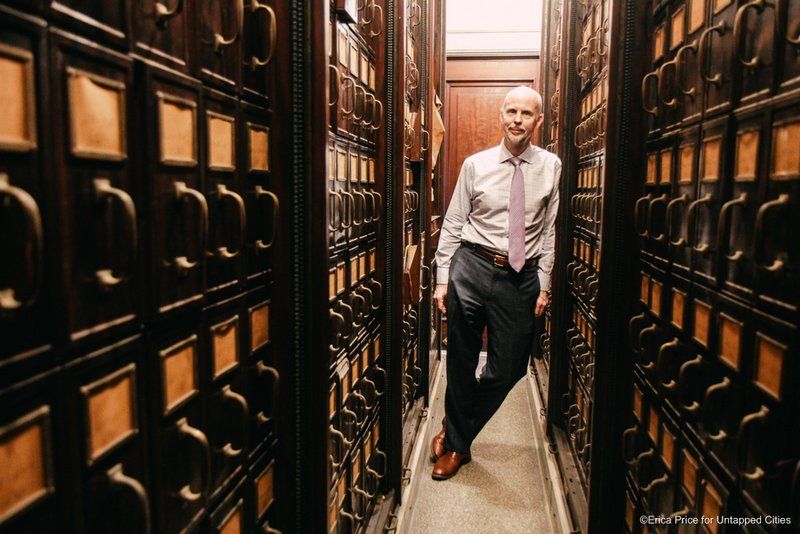

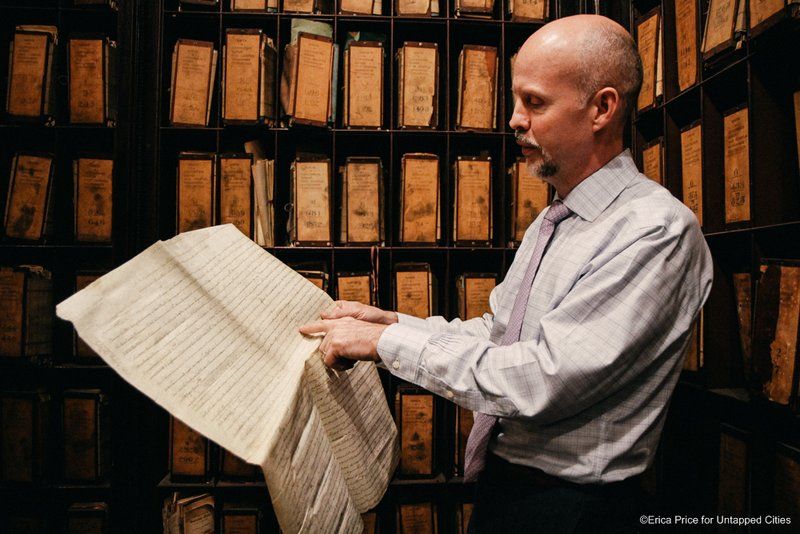

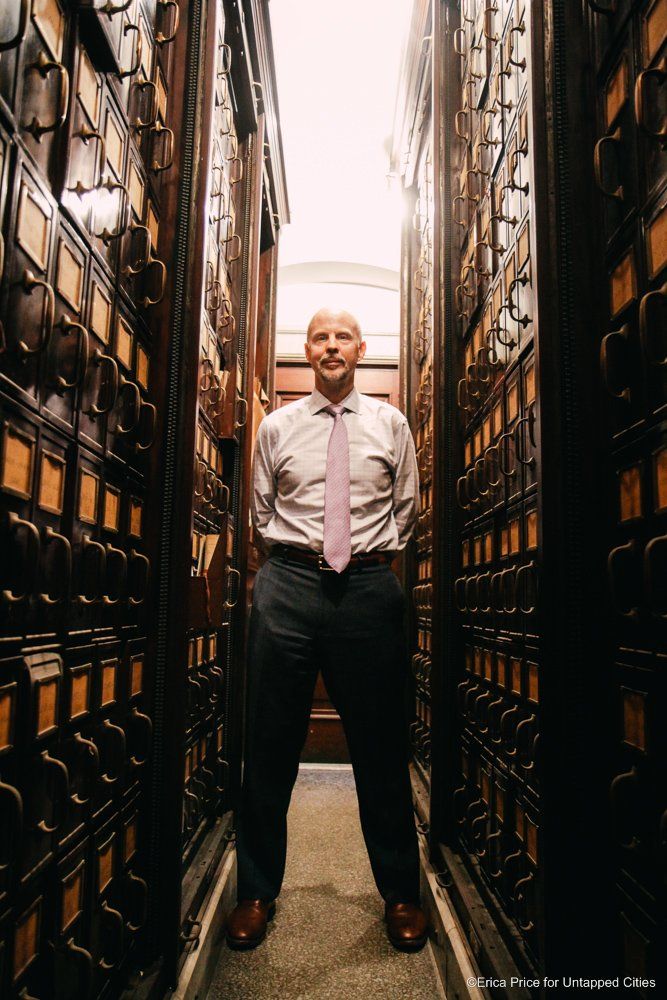

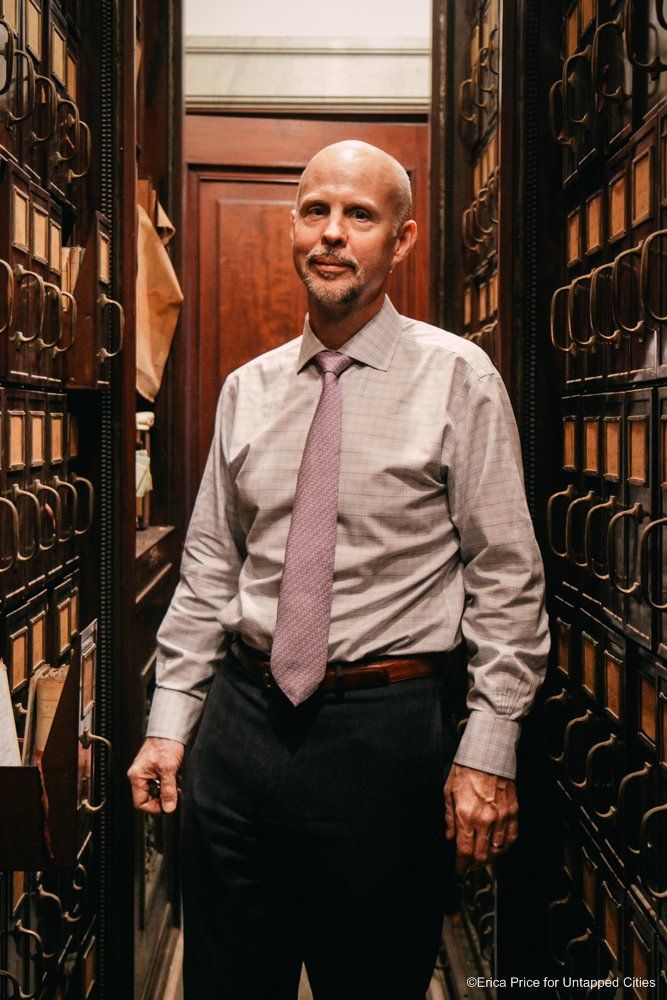

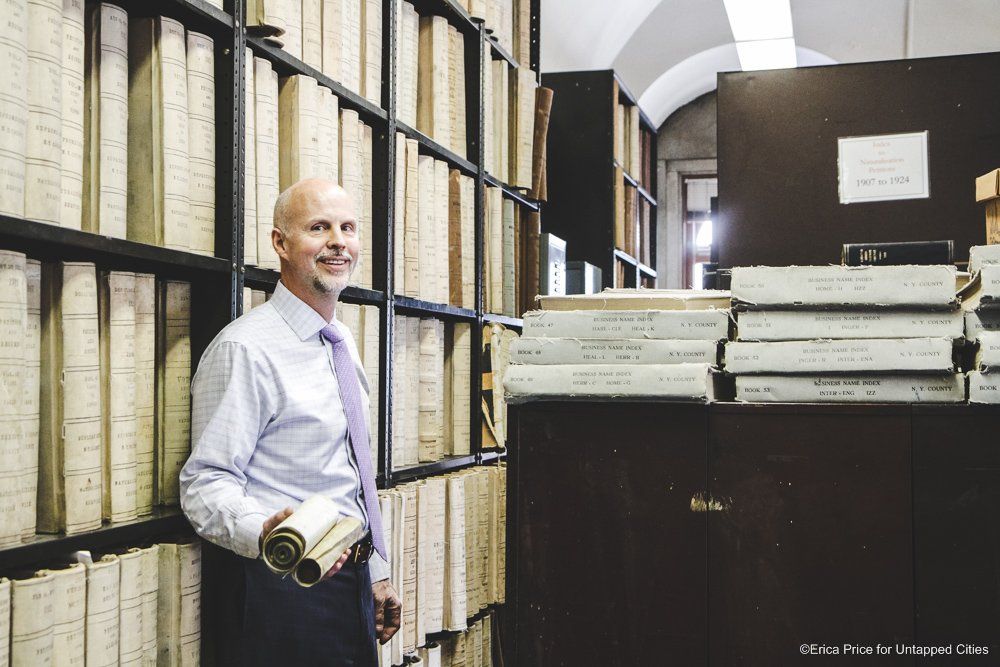

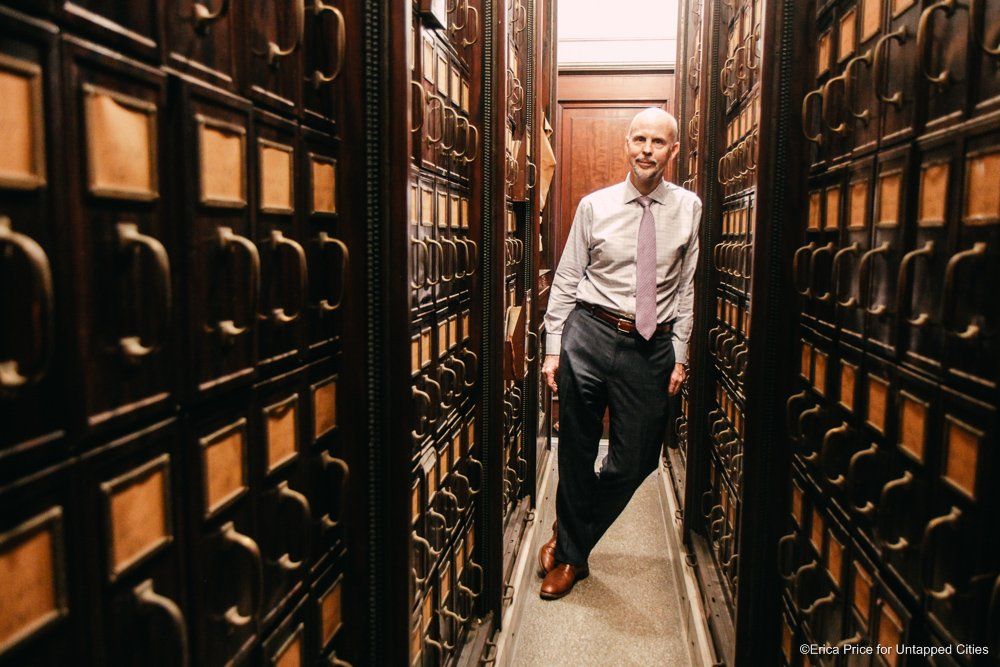

Inside the Department of Old Records in New York City with Chief Records Officer, Geof Huth

If the Untapped Cities staff could conjure up a vision of heaven, it would probably be the New York City Surrogate Courthouse’s Division of Old Records. The name itself suggests a little of Hogwarts mixed with a lot of old New York, and the place certainly lives up to its imaginary potential. With records that go back to 1674 and documents signed by the likes of Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr, it’s a treasure trove of New York City and American history.

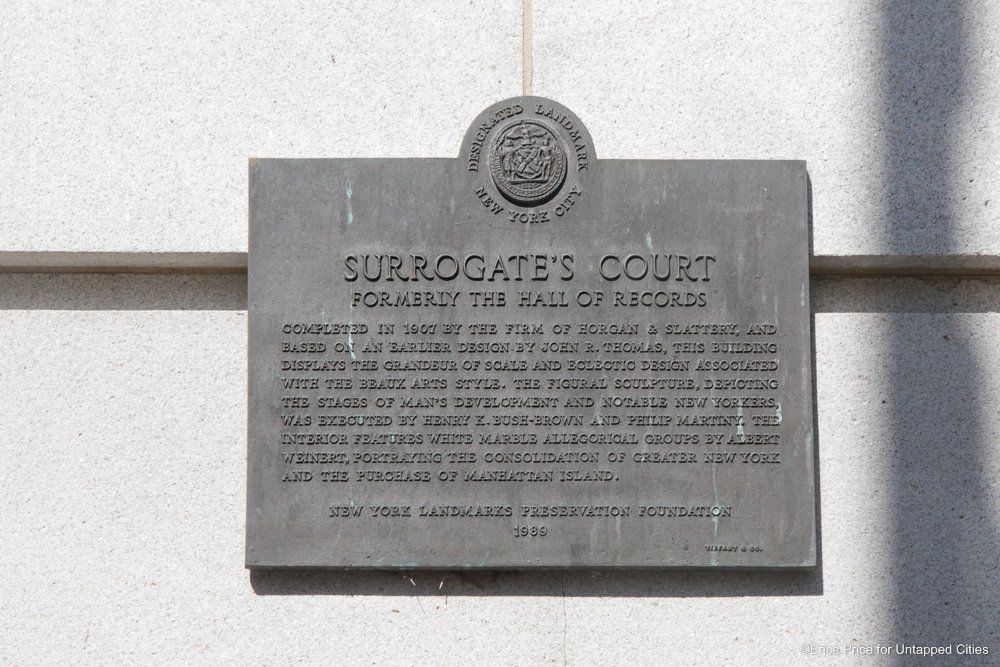

Far from a basement archive, the Division of Old Records is located on the top floors of the stately Beaux-Arts style New York Surrogate’s Courthouse where the Municipal Archives is also situated. The building is a formidable architectural competitor to nearby government institutions like the Tweed Courthouse, the Municipal Building, and City Hall.

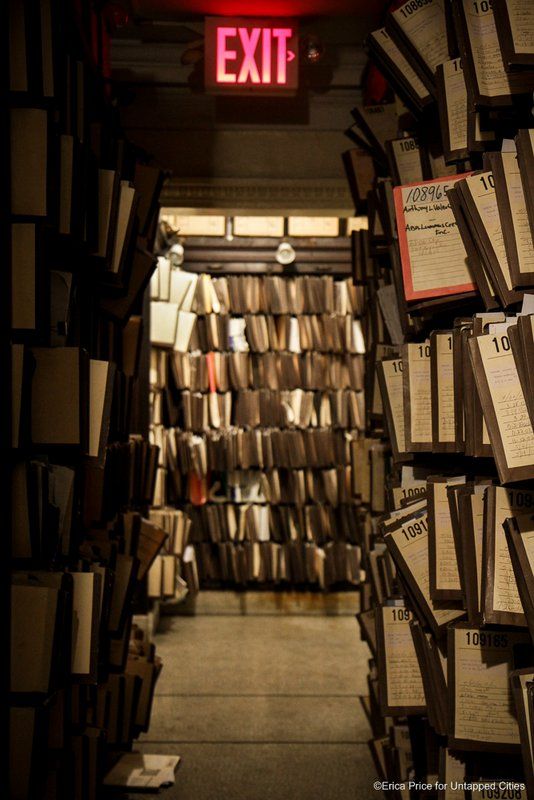

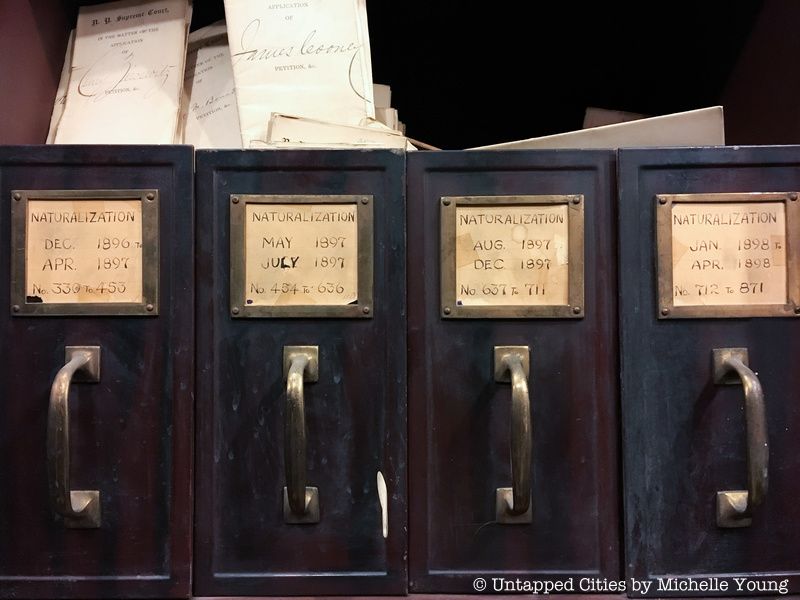

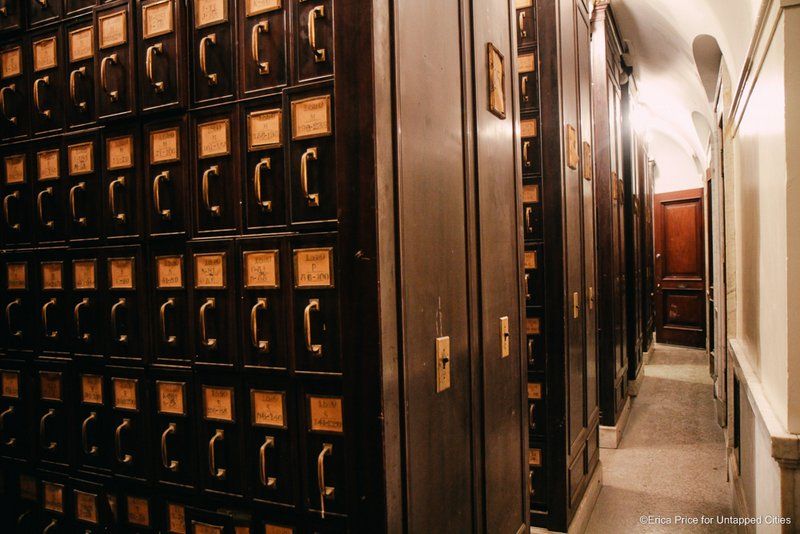

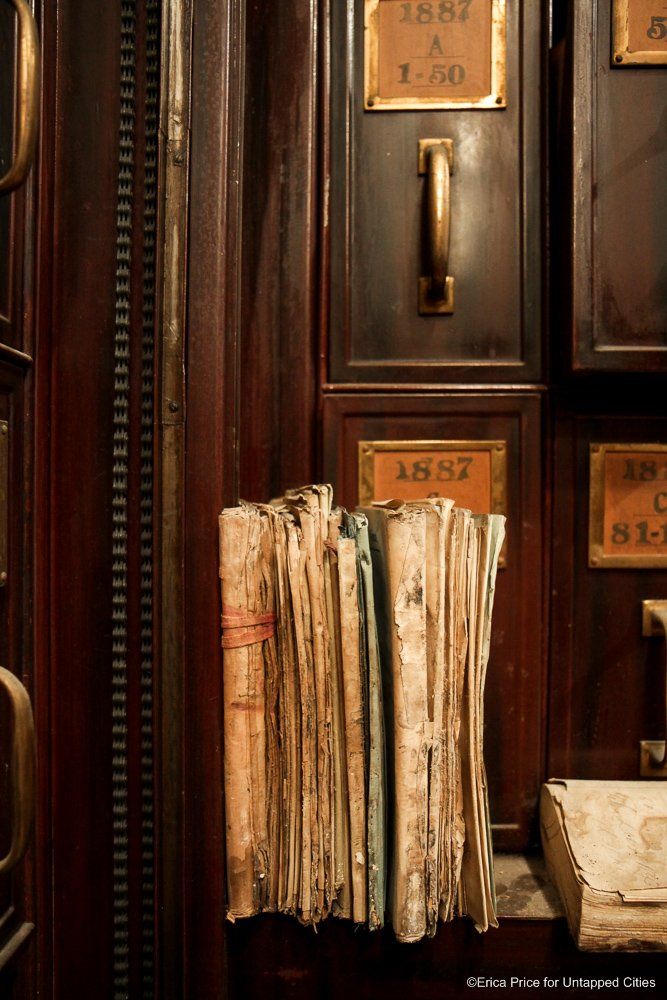

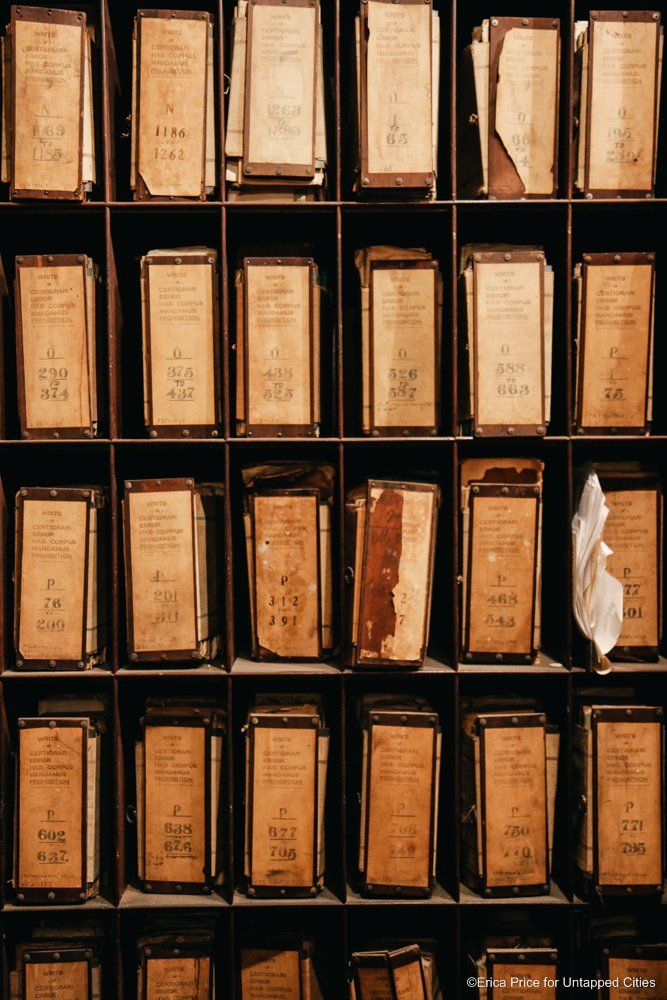

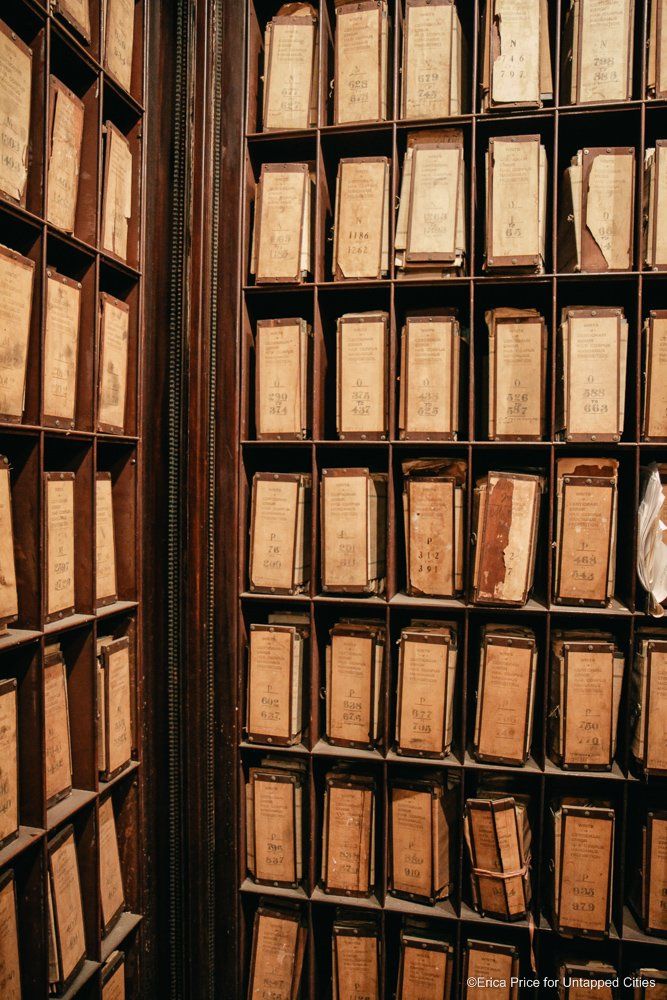

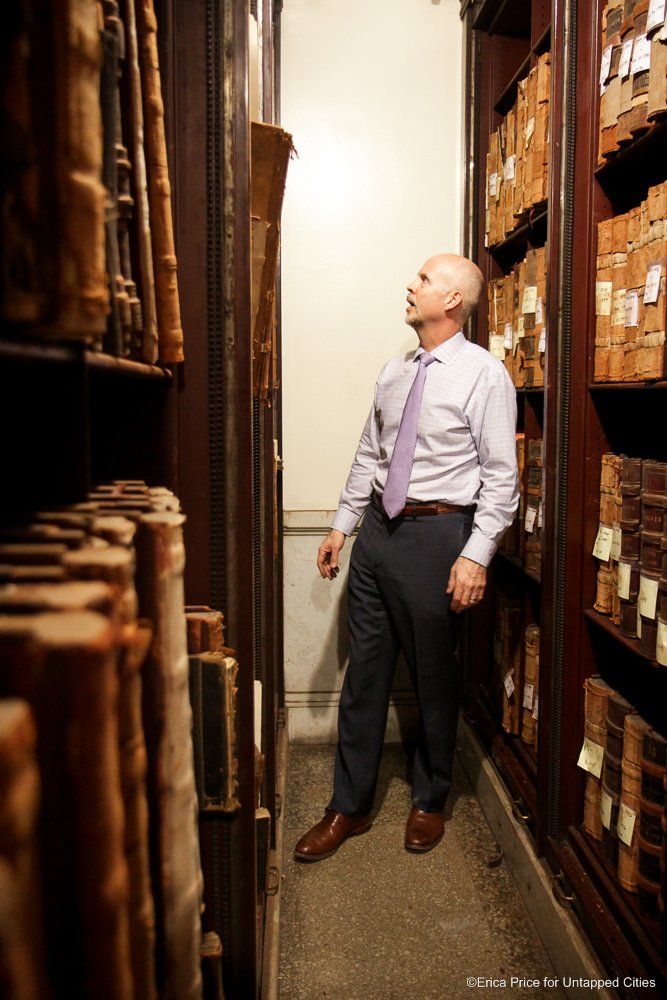

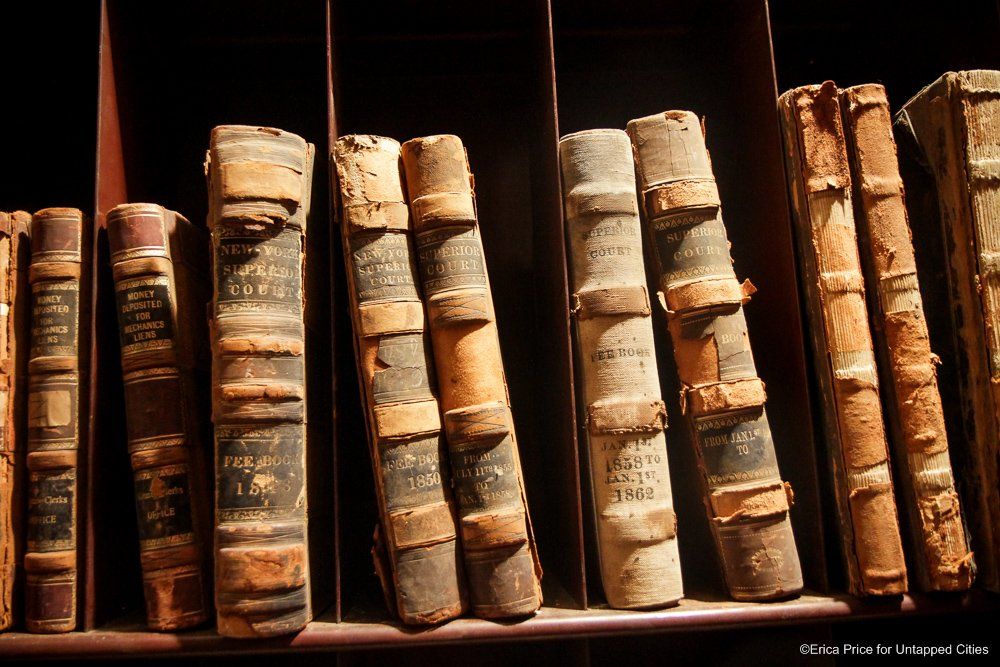

The Division of Old Records is like a chamber of secrets. From the moment you step out of the elevator, records will confront you from floor to ceiling, on bookshelves and built in wooden storage cases, along a maze of hallways and in many rooms varying from cubby sized to lofty. In addition to the seemingly countless documents on these floors, there are about a million additional boxes in inactive storage.

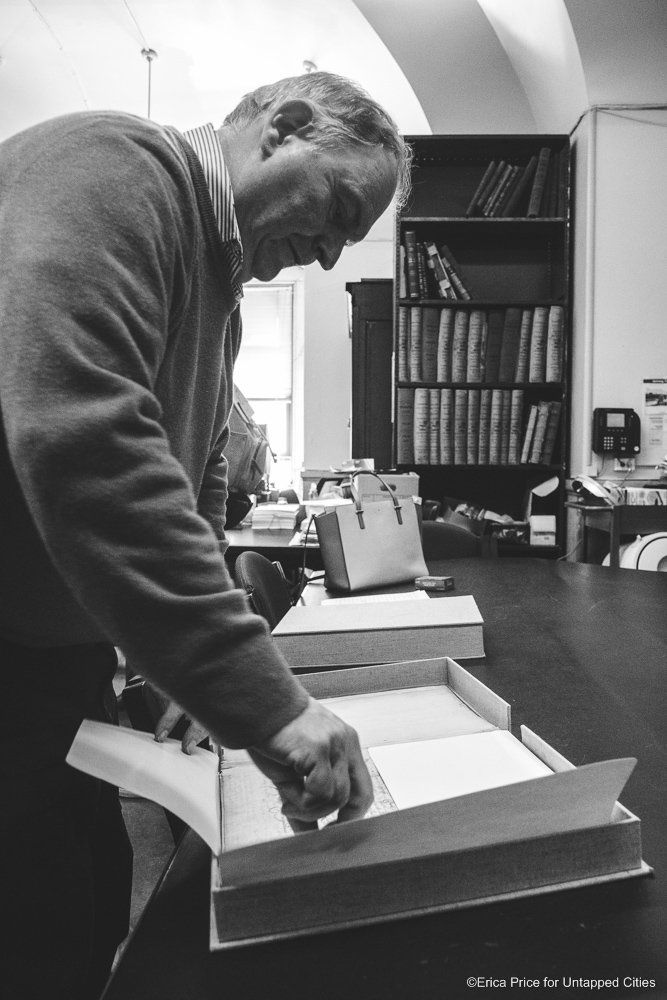

We recently visited the Division of Old Records with the passionate people in charge – Geof Huth, Chief Records Officer, Joseph van Nostrand, archivist for the Manhattan county clerk, and Jane Chin, Deputy Chief Records Officer – who organize and save the historical documents for posterity. We also recorded a Facebook live video of part of the visit. As van Nostrand tells us, “We’re concerned about preserving the records for the future and giving people access to them. Because I’m all by myself here, and we have a few staff members, but they’re not going to replace anybody that leaves.”

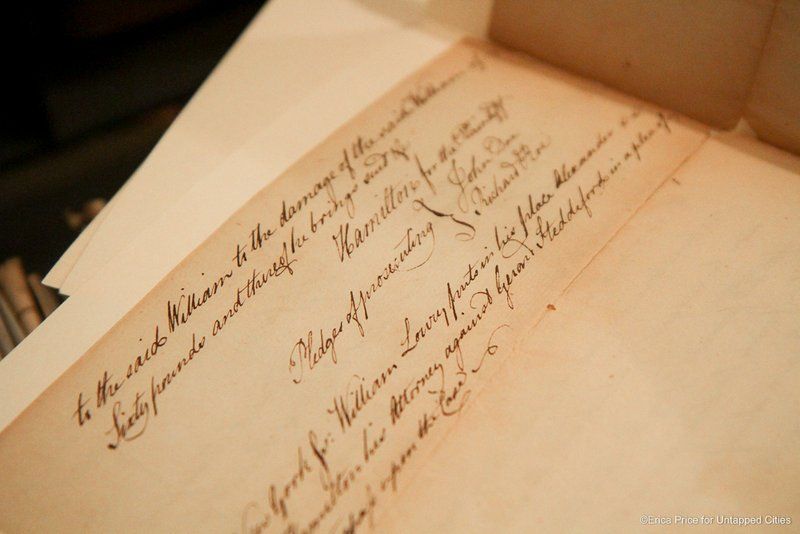

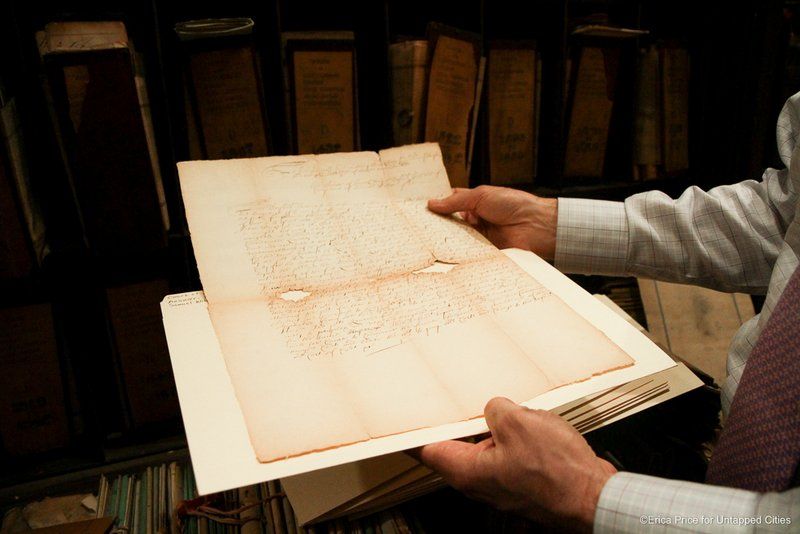

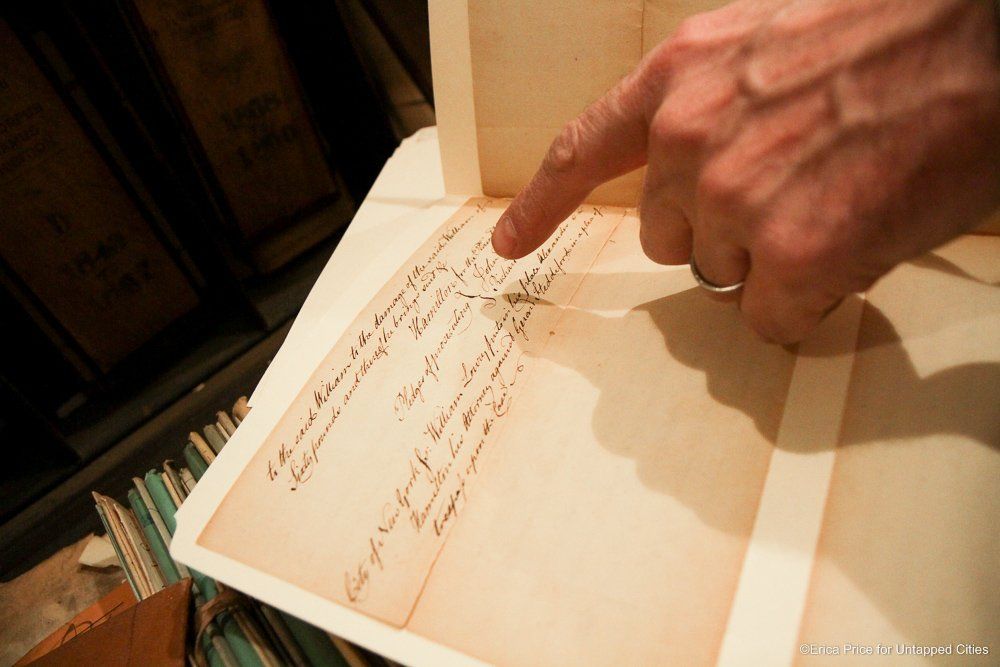

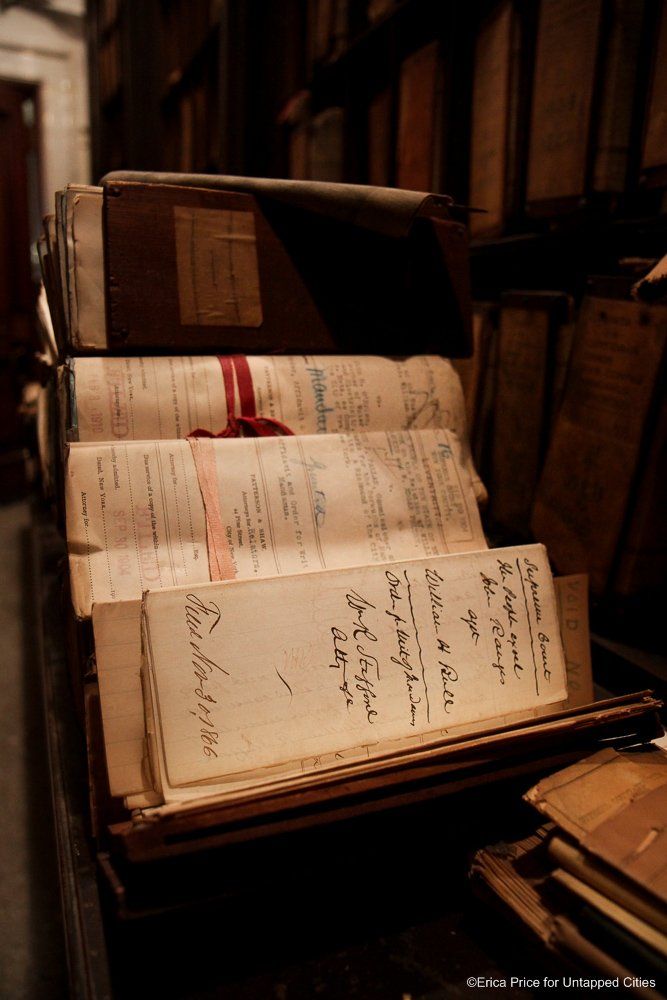

A document signed in 1784 by Alexander Hamilton, who is writing for the plaintiff in a case involving a William Lowry.

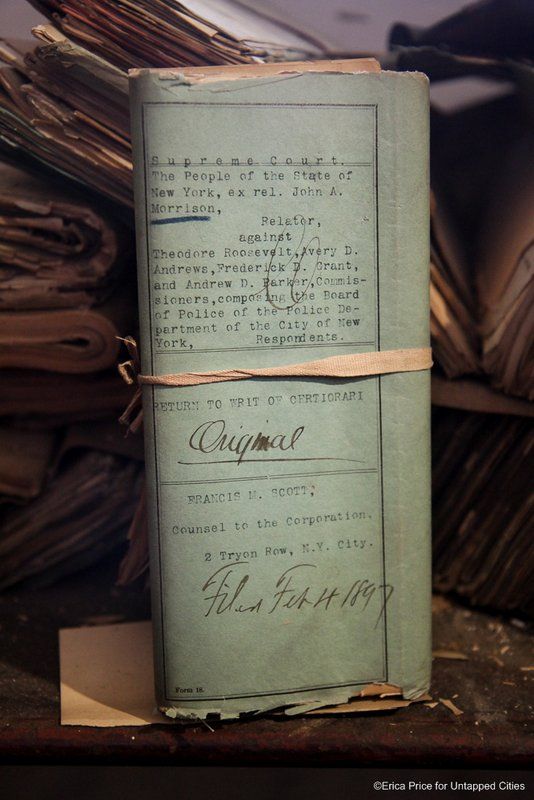

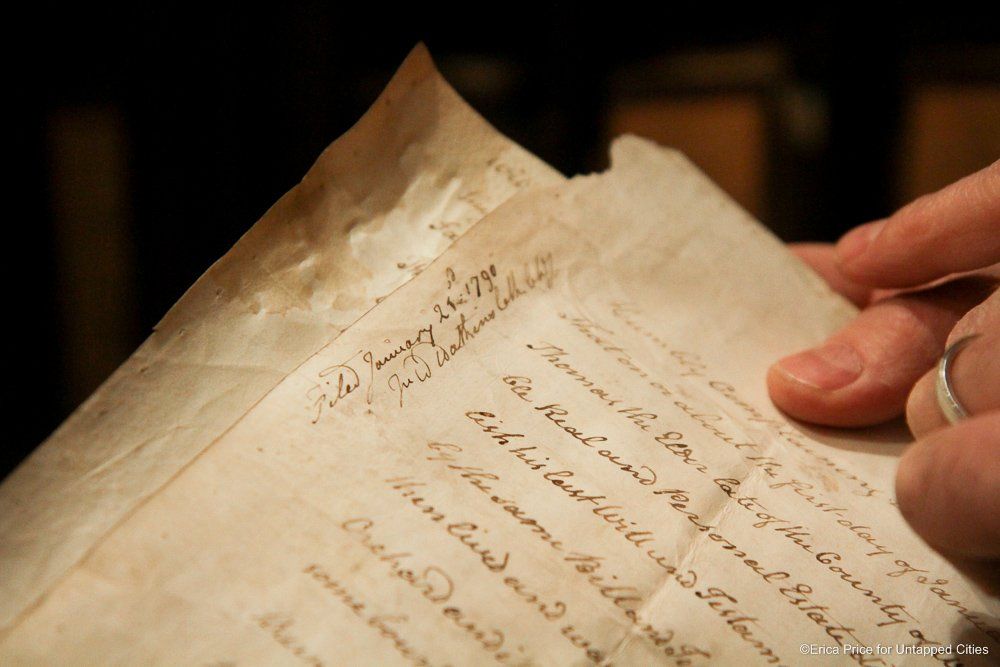

Some notable documents that Huth and his team pulled for us to view included handwritten papers signed by Hamilton and Burr when they were lawyers for New York City, a court case against Theodore Roosevelt and his fellow Commissioners when the future President was serving on the Board of Police in New York City, and a case for slave release argued by another future President, Chester A. Arthur.

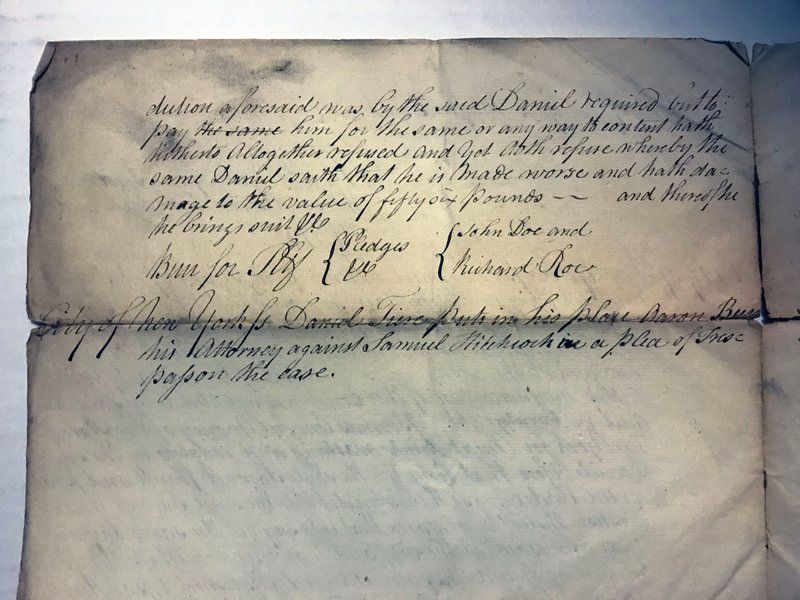

A document signed by Aaron Burr for a civil proceeding, found in the same box as the one from Hamilton. Burr is also representing a plaintiff in this case.

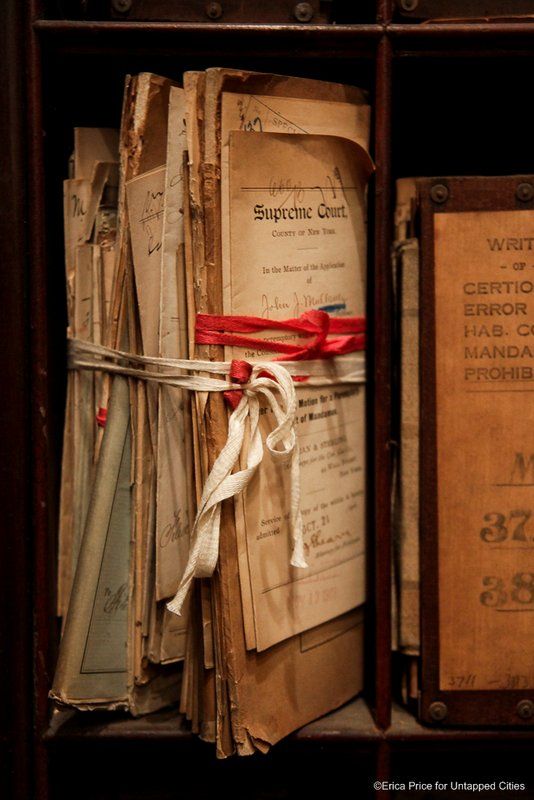

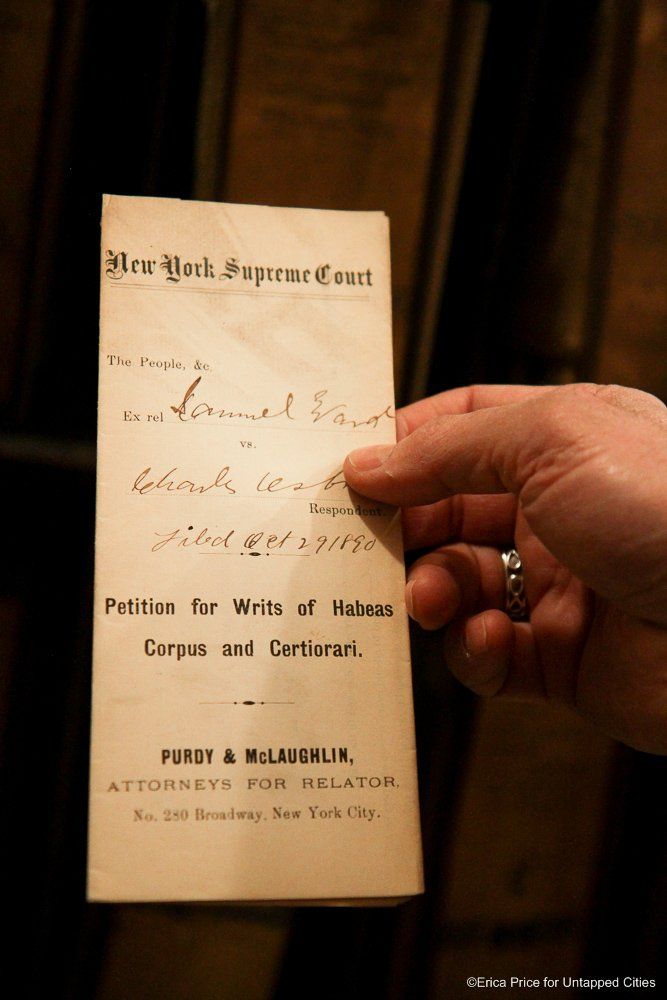

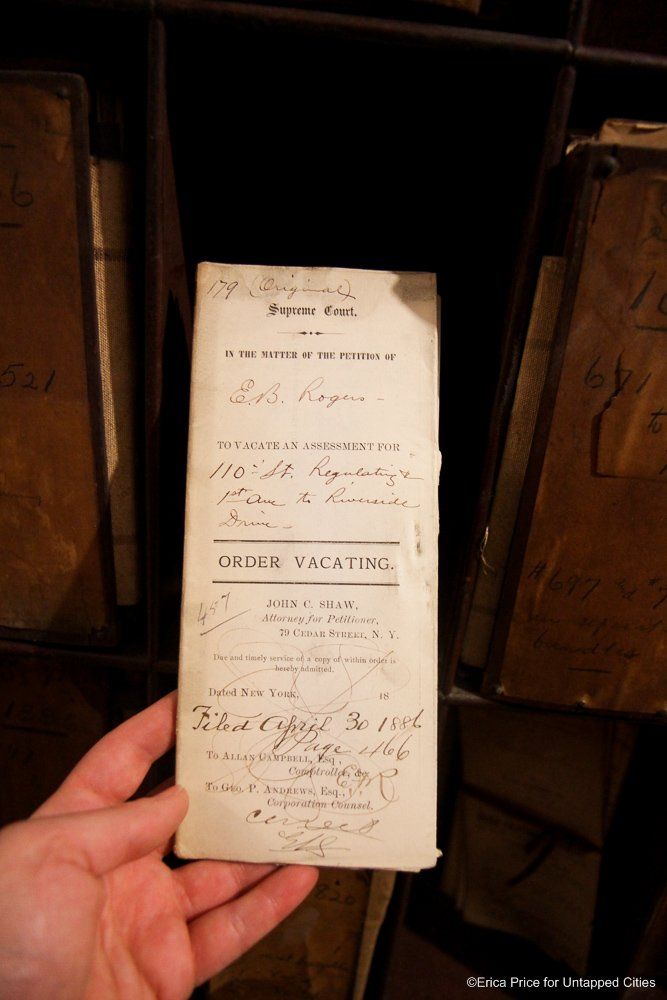

A case involving Theodore Roosevelt, a commissioner of police in New York City at the time

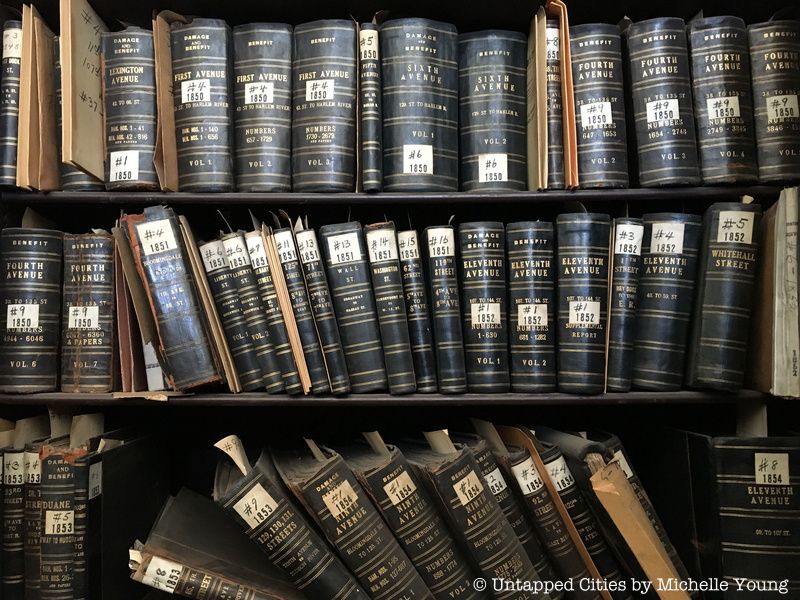

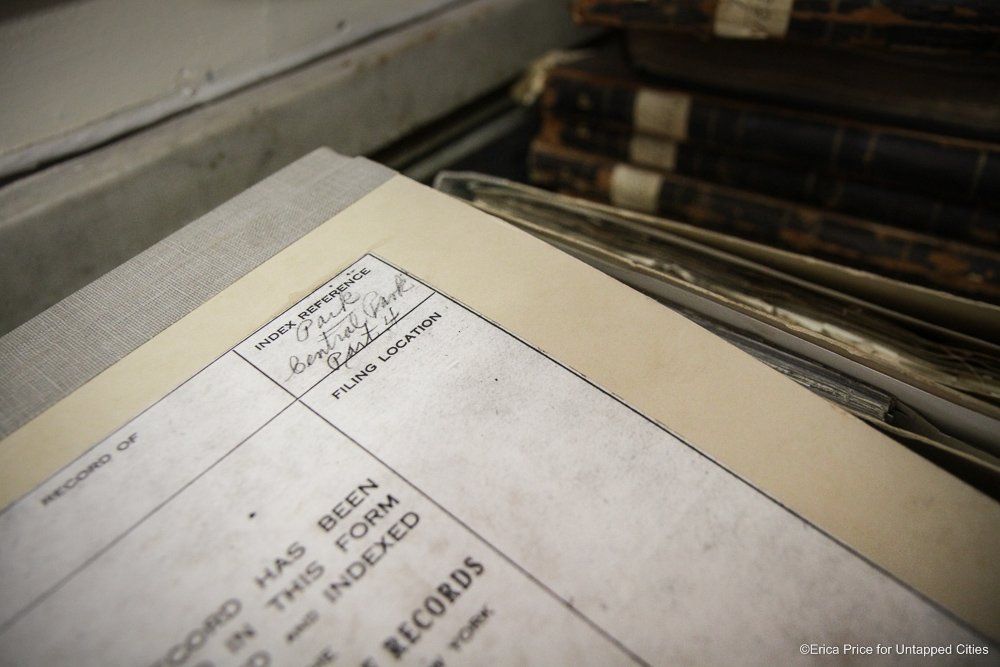

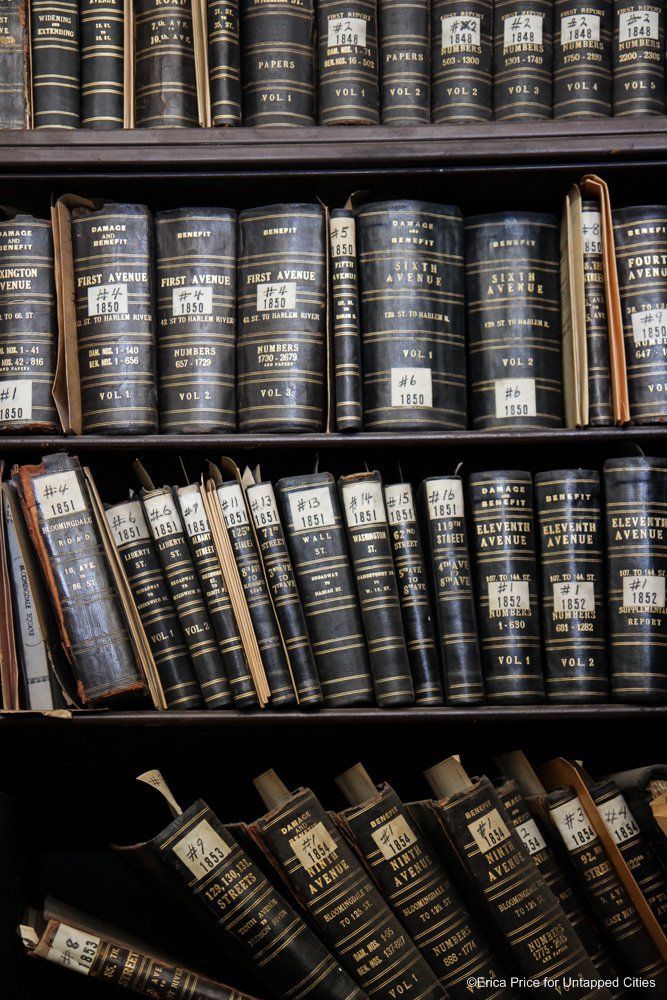

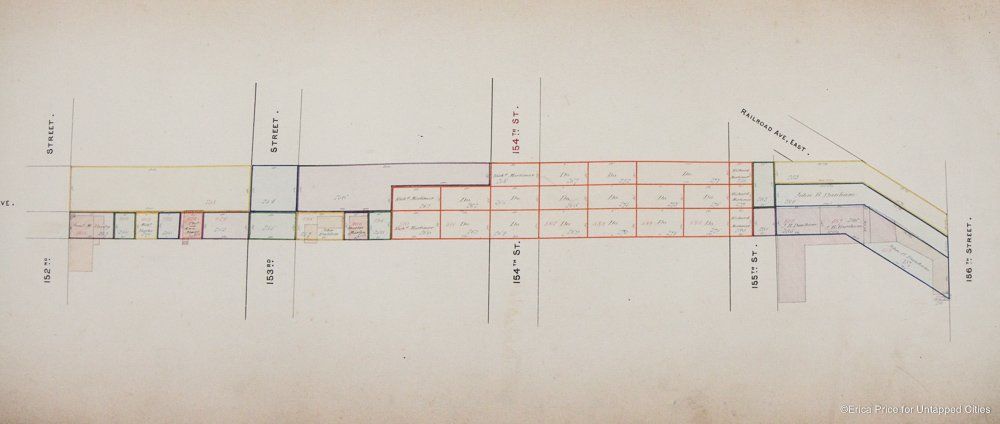

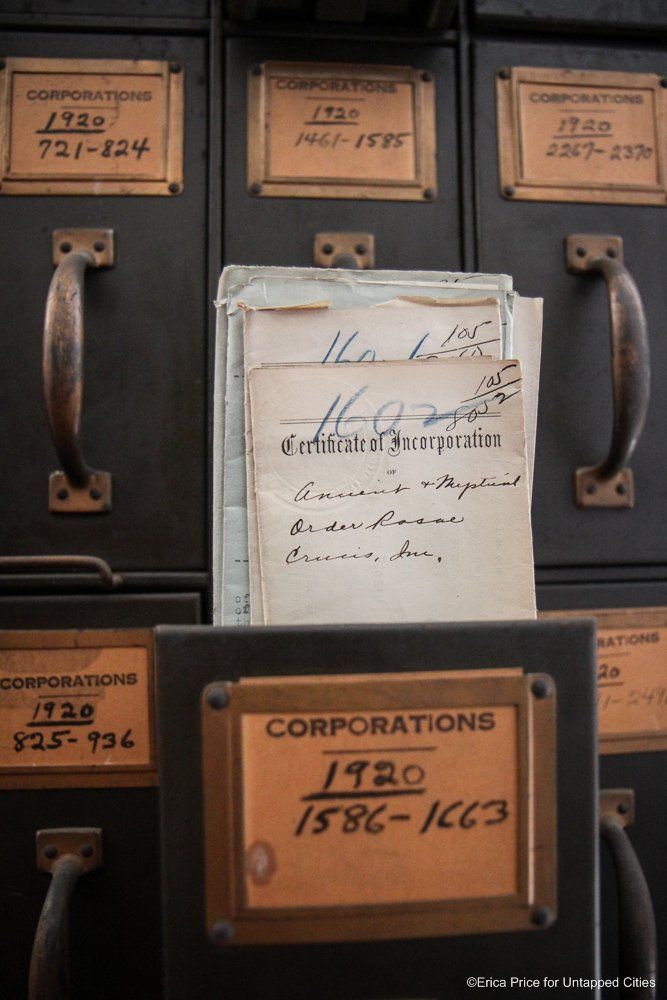

The courts also handled immigrant naturalizations, corporation formation, and eminent domain cases for the expansion of New York City. A large portion of one room shows condemnations for new avenues and streets, and for the creation of famous parks like Central Park, Riverside Park and more.

Books of condemnation and eminent domain documents for the creation of new avenues, streets, and parks in New York City

In January, the New York Times reported that a large set of records was being transferred over to New York State, but in truth, they represent just a little over 10% of the total collection, about 1500 regular sized bankers boxes. New York State acquired all of the Court of Chancery records, a state-wide court that existed until 1847 when it was abolished. “They wanted records that didn’t just reflect New York City, but the other counties,” says van Nostrand. Huth elaborates further than the state archives are responsible for documenting the state as a whole, “and these were the documents of state-wide significance.”

van Nostrand continues, “We feel that many of the records were getting older and deteriorating, and we weren’t getting any resources, so we’ve started to turn them over. A group went to the state archive. The only ones they would take, we sent them. We had plenty more, but they only wanted a certain amount, and they took them. And we are trying to negotiate right now with the city archives because as you can see, we have a lot left!” Huth estimates that about 6000 to 9000 boxes will be relevant to the Municipal Archives.

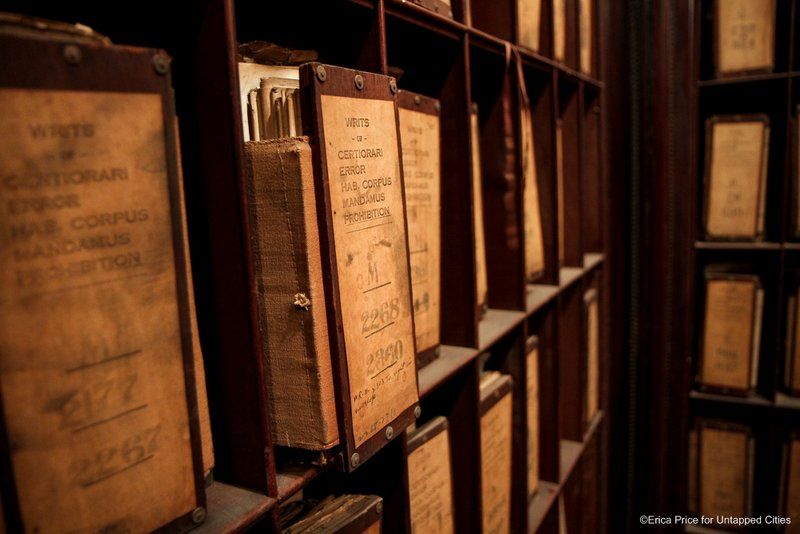

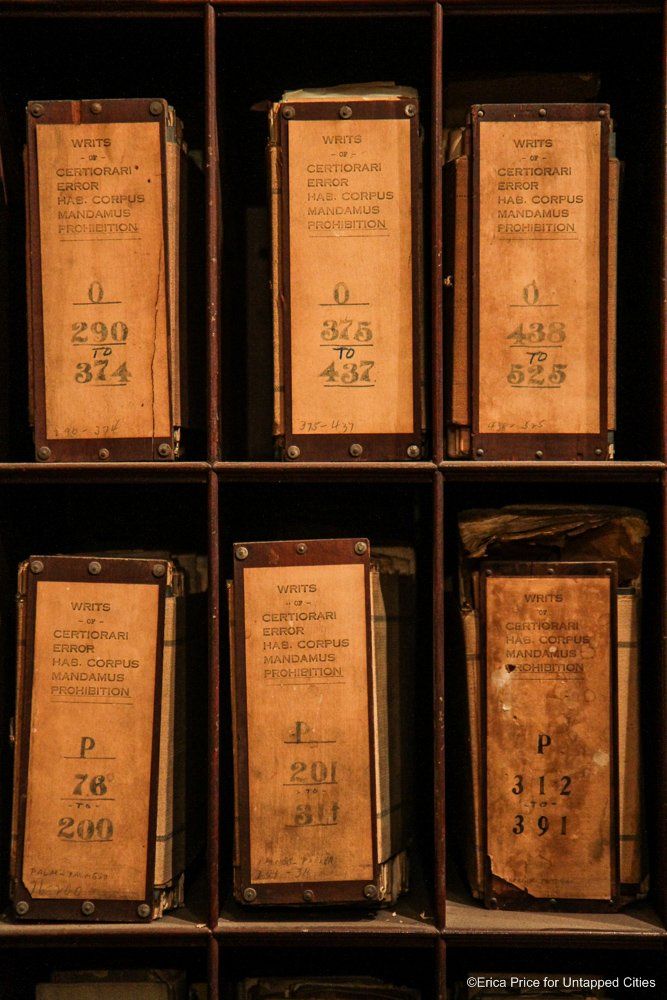

In terms of the daily work here at the Department of Old Records Huth says, “What my staff is doing right now is boxing these records, describing them, confirming what they are. In cases where the records have split up from each other, bringing them back together.” In fact, he was working on just that on our visit where he had found writs that belonged to the Supreme Court in the 1830s, the time frame the State Archives were interested in. Writs, Huth explains, are “short documents put together by the court commanding people to do certain things.”

Jane Chin, Deputy Chief Records Officer

The original keys to the 8th floor, where the archives are located

The original keys to the 8th floor, where the archives are located

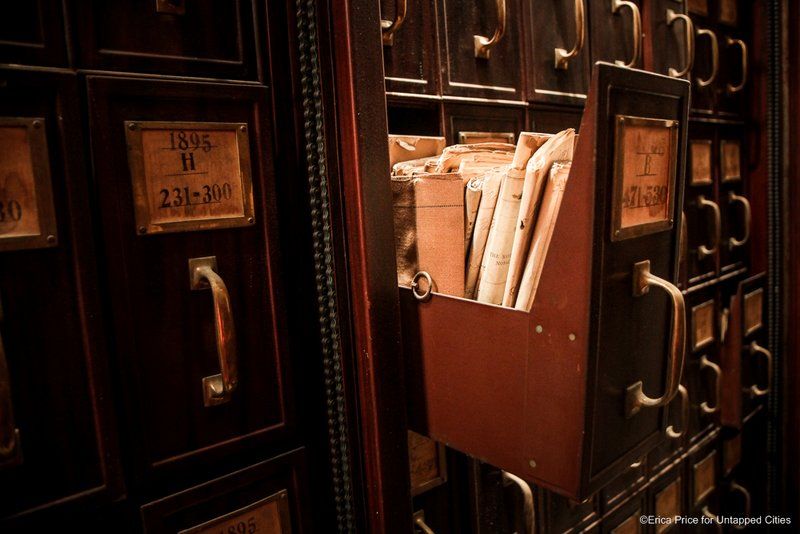

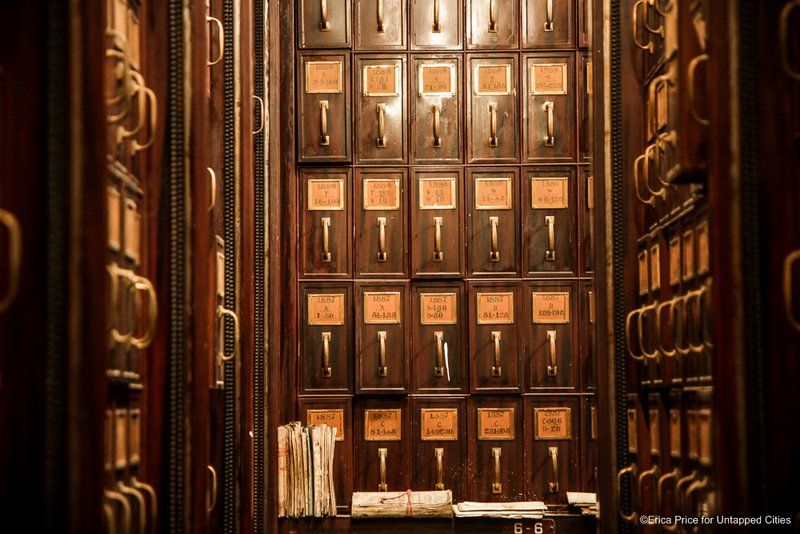

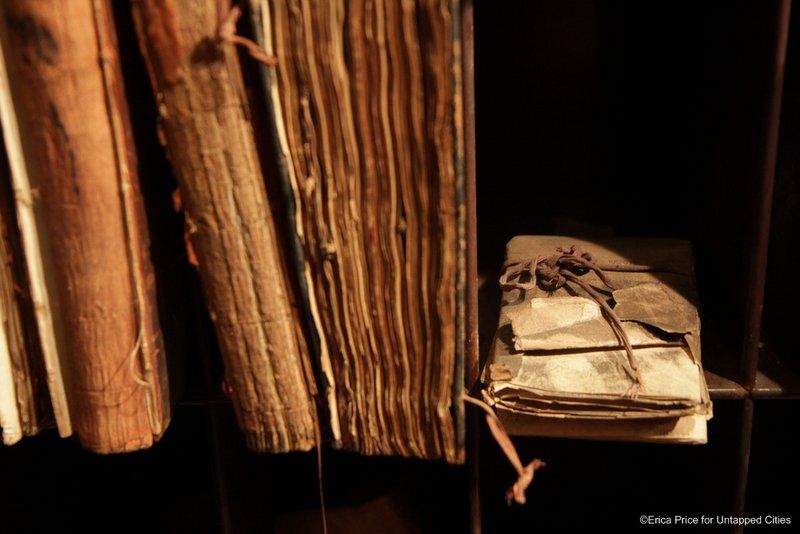

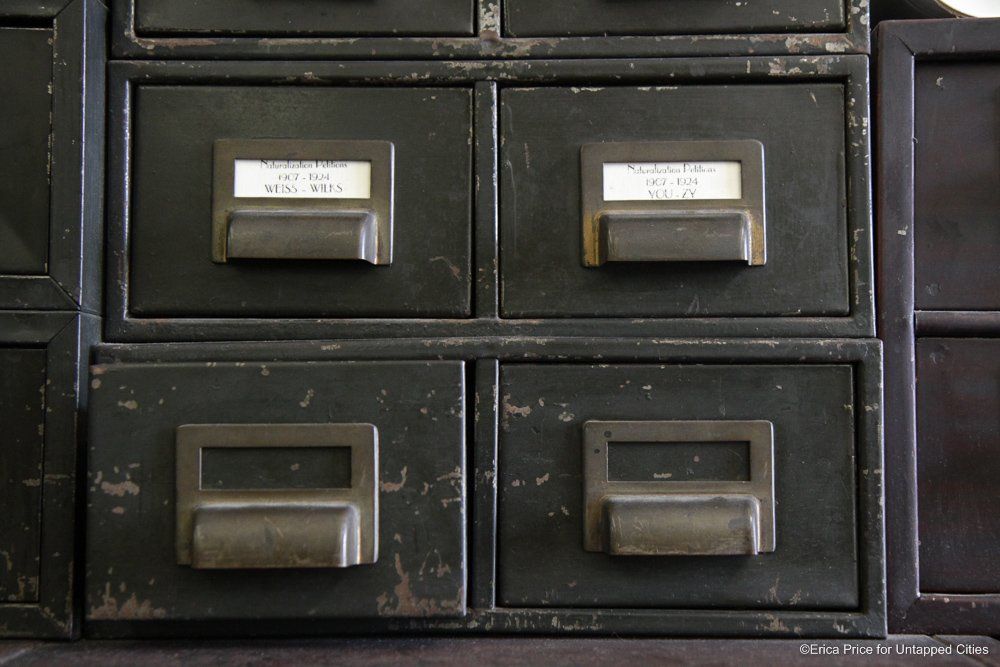

In the room we broadcasted live from, the writs were located in metal Woodruff files an advanced filing system developed during the Civil War. “Filing before used to be, you bundled things and put them in piles. Unless you rolled [the files] and put them in piles. This kept them in some semblance of order. They could logically go back to them,” says Huth.

A Woodruff file

The Woodruff files in this particular room were put in sometime between 1907 and 1911. The shelves also had a rolling door that could be pulled down from the top to protect from theft. “Theoretically, but probably not actually from fire.” There is also a hybrid system in place, combining the Woodruff file with another system known as the Willis file, which held files within canvas. Original light sconces are also still in place in the archives.

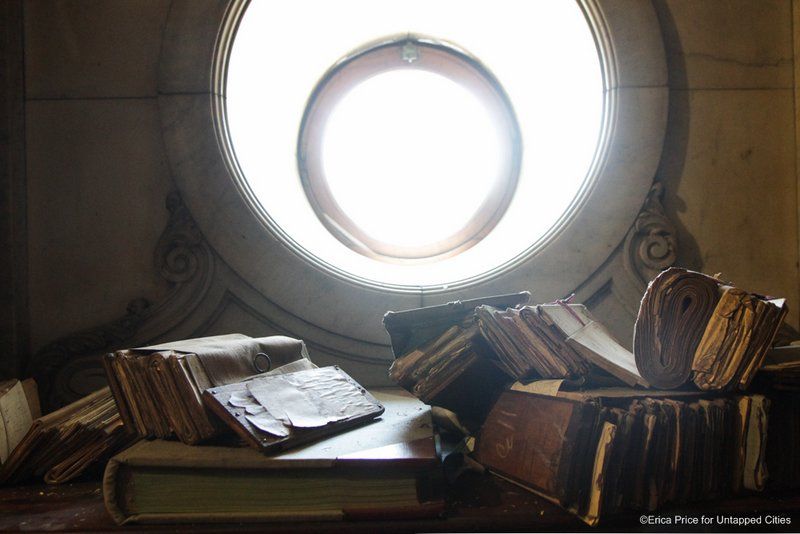

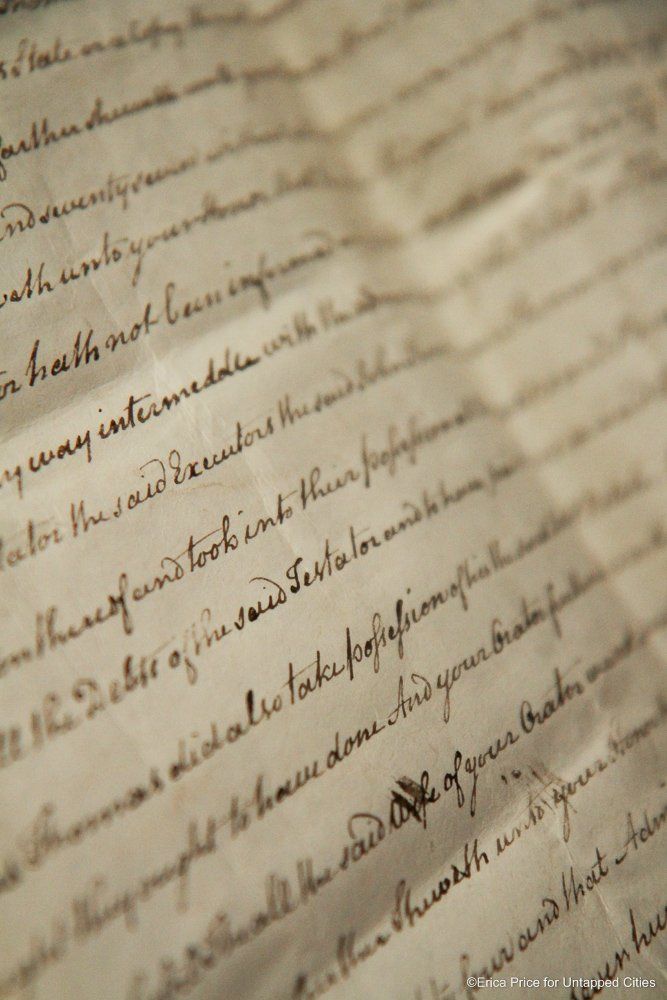

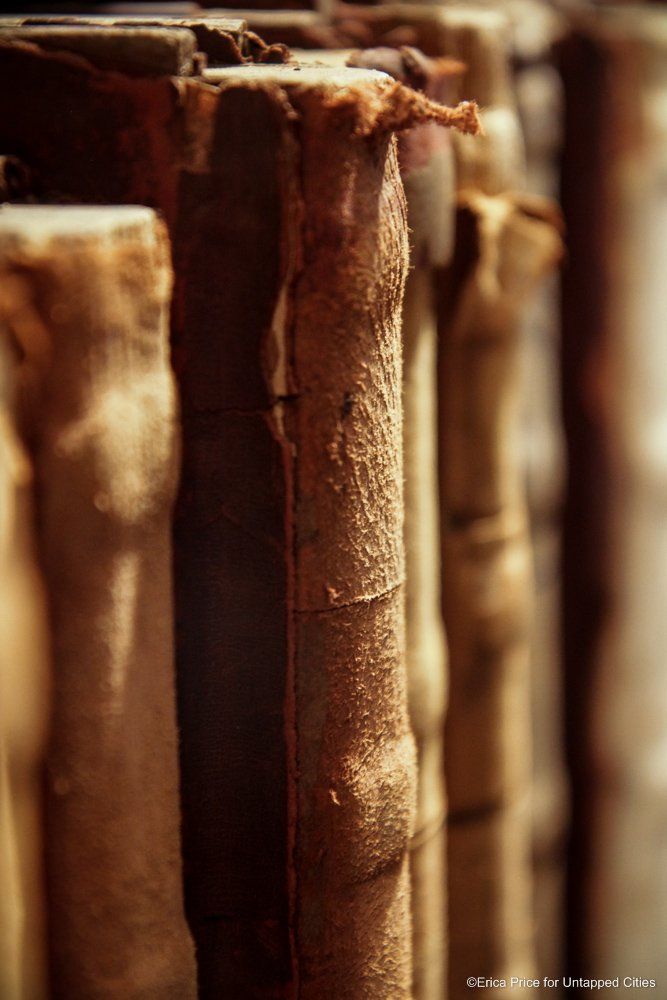

Some of the rarer types of documents in the archive are written on parchment, reserved for the most important cases. The practice was passed down from the United Kingdom, which only recently stopped using the material. Paper, Huth explains, particularly those from between 1859 and 1990, even high quality ones, contained a lot of acid and lignans and have deteriorated over time. On the other hand, “parchment remains pilable, virtually forever. There’s almost nothing that makes it brittle or hard. [It’s] an incredibly durable medium.”

Huth, in front of Wilson files holding a parchment document from the Court of Chancery.

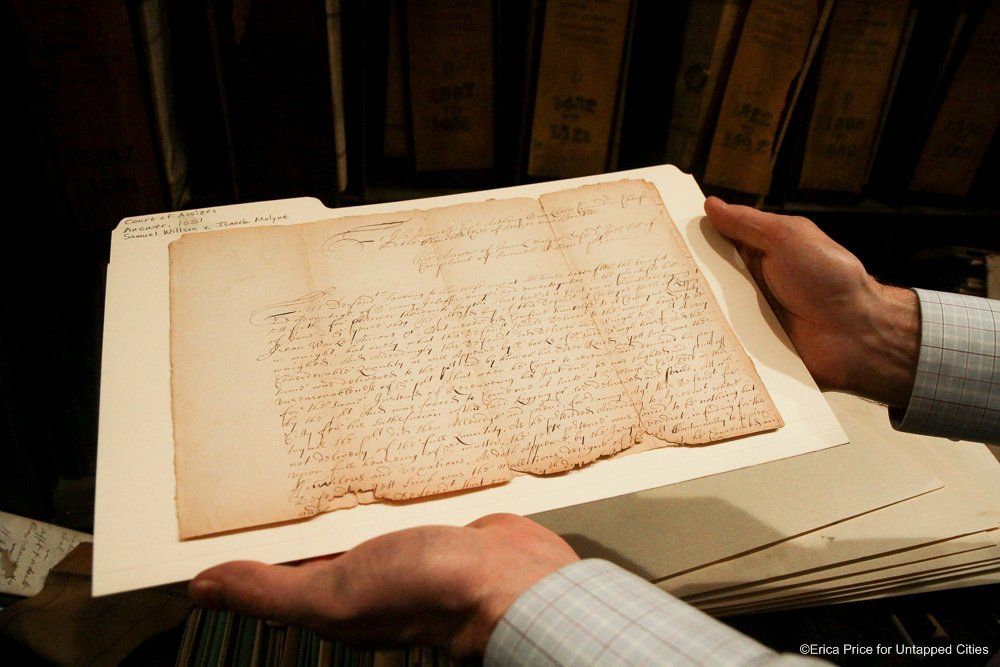

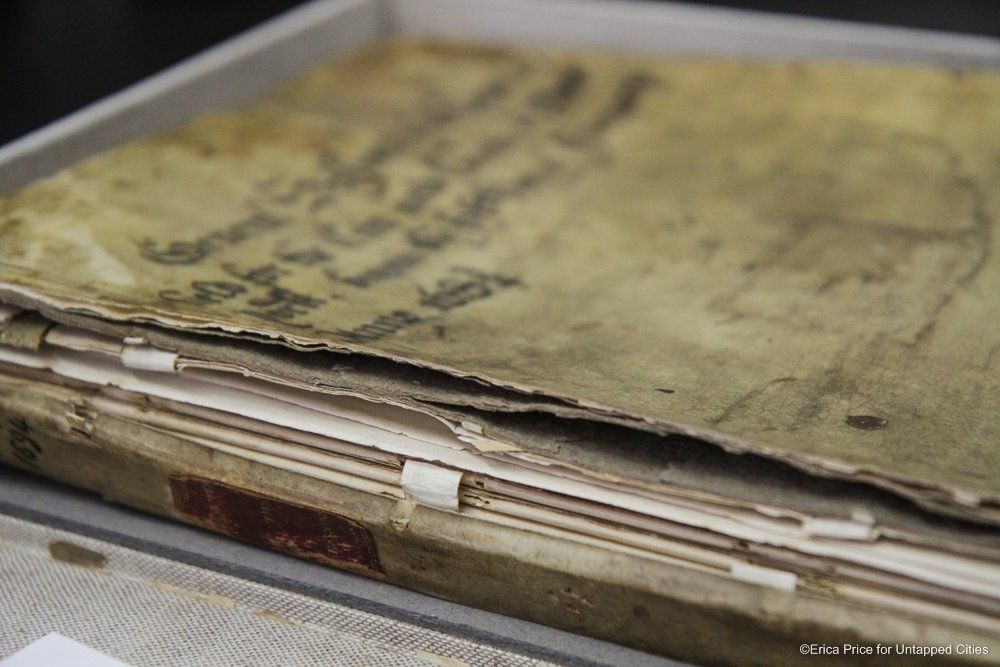

There is also the earliest record that we will be given to the New York State archives and its material and state contrast sharply with the parchment document. It dates to 1681 from the Court of Assizes, a predecessor to the Court of Appeals, the highest court in New York State. Huth says, “It’s still readable, but very fragile. There are voids where paper has flaked away…After this court, the only way in 1681 to have a chance to win in your case if you lost in this court was to go to the King. And King didn’t want to talk about many people.”

1680 document from the Court of Assizes

As public records, the idea is that anybody can request documents, hold them in their own hands and use them as research. Usually, requests go through the department and a staffer will pull the files. Nonetheless, “we expect them to be used,” says Huth.

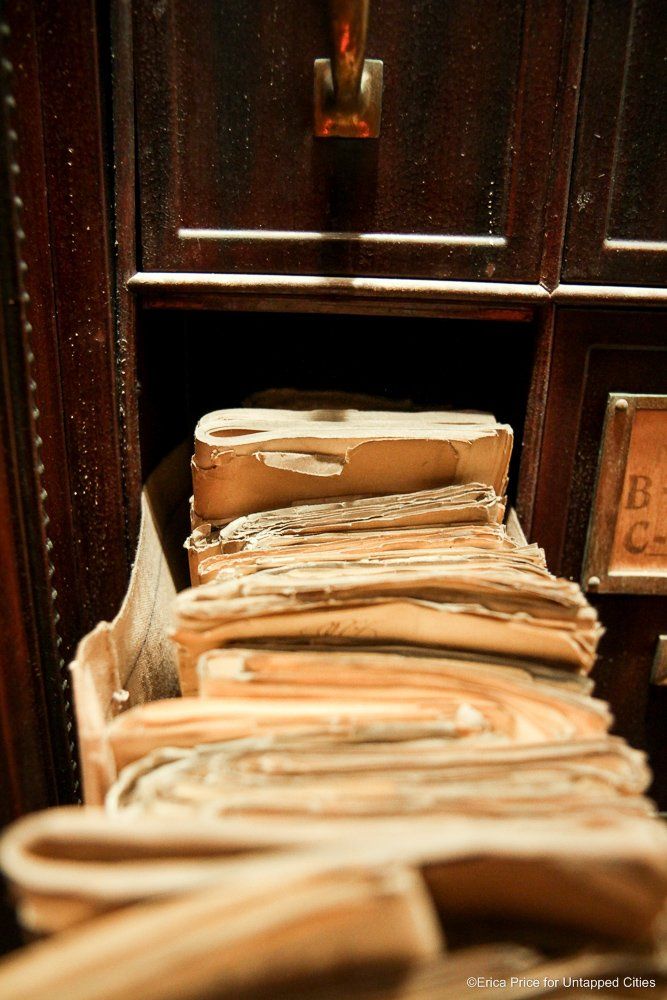

A dusty file, waiting to join some fellow records

Even though the Woodruff filing system is in great condition and still operable, Huth explains some of the challenges of maintaining an archive in the current conditions, which explains part of the urgency on the part of the staff to move documents where they can to more modern storage facilities. “Even if you enclose [the documents] in the Woodruff boxes, Huth explains, “dust will collect on them. In modern archives now, you have cleaners that are pulling dust out, cleaners will go and dust off the top of the boxes.” But with the number of Woodruff boxes in each unit, “it would be kind of impossible to dust all of those periodically,” says Huth. In addition, the wheat paste binding of the documents has simply not withstood the test of time.

“What this really shows is that the court system was virtually incapacitated by how much paper they had to manage. Managing this paper physically became very, very hard, that’s why in the modern court system, where I do most of my work, we’re trying to make everything digital so we can move things faster, save time.”

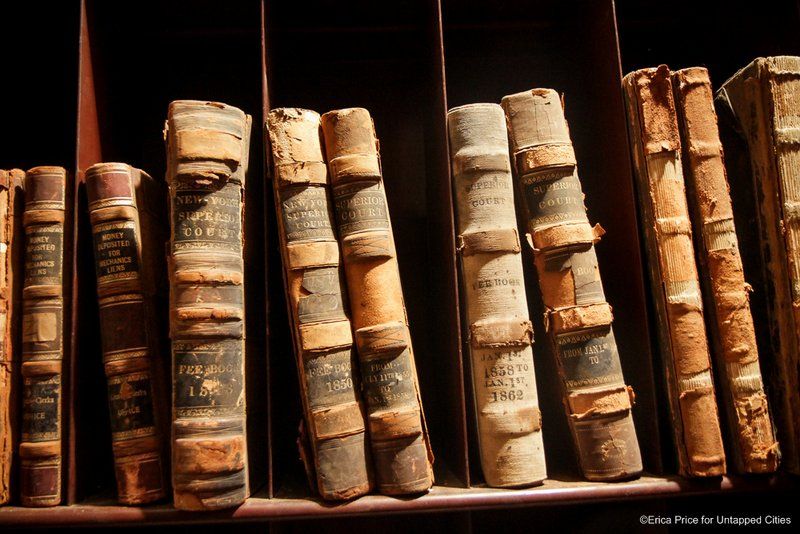

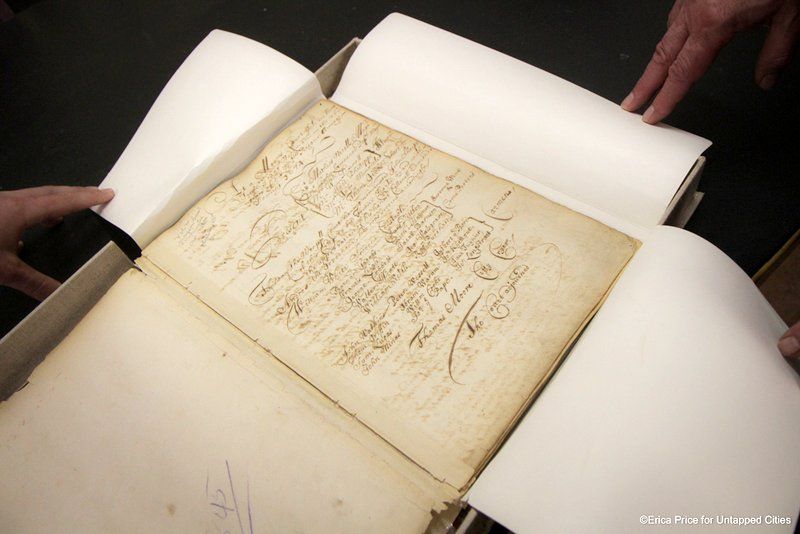

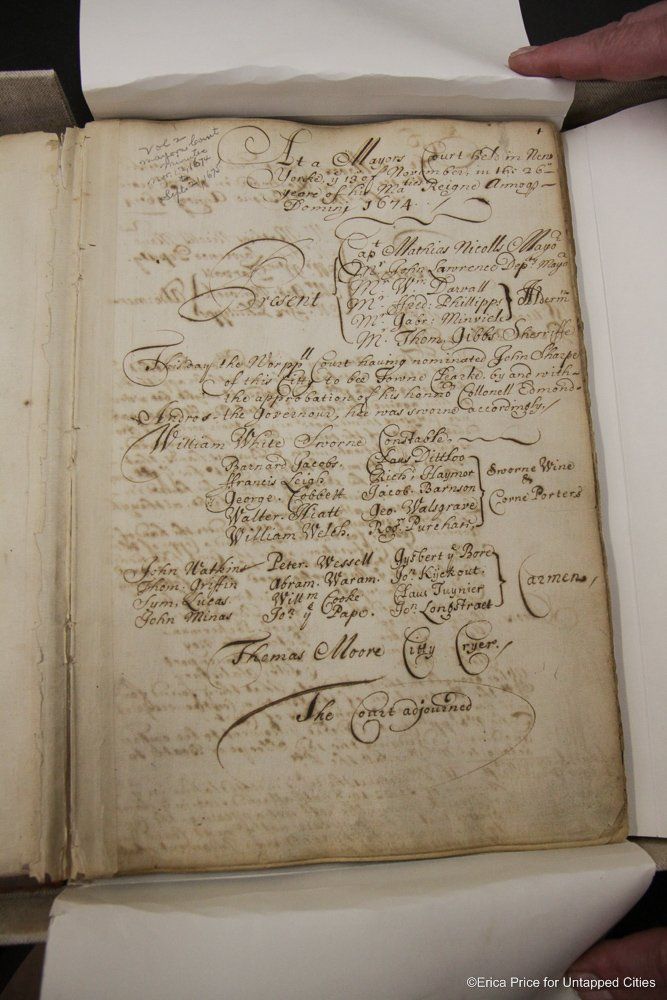

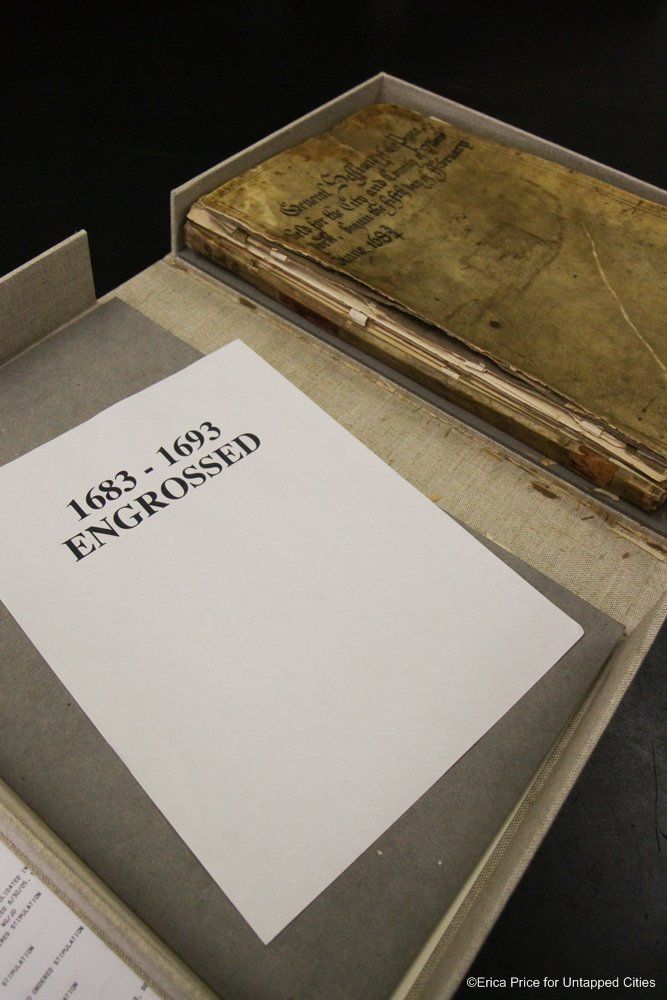

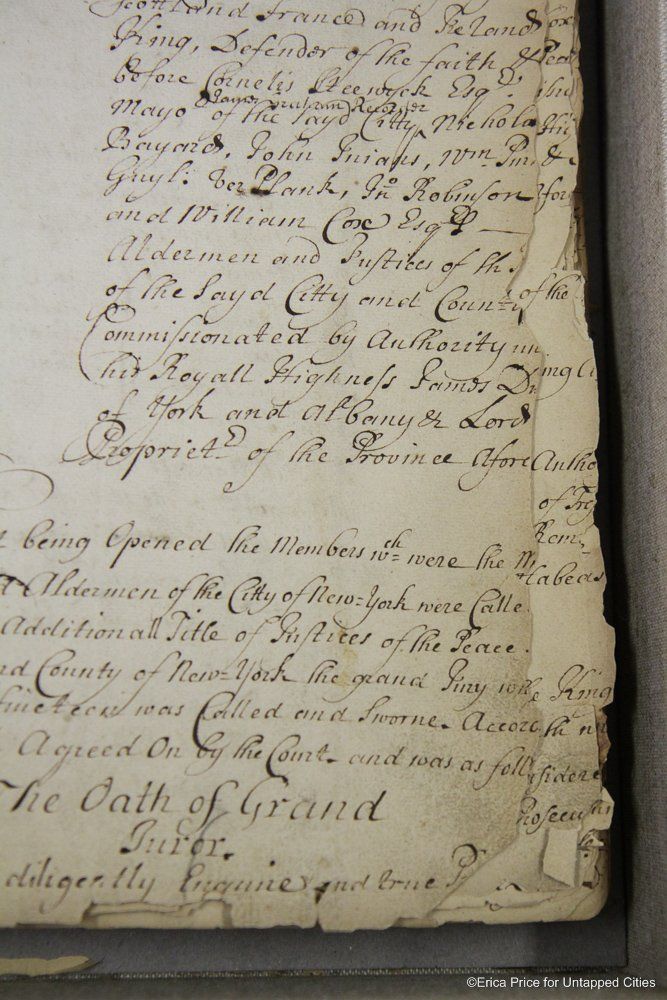

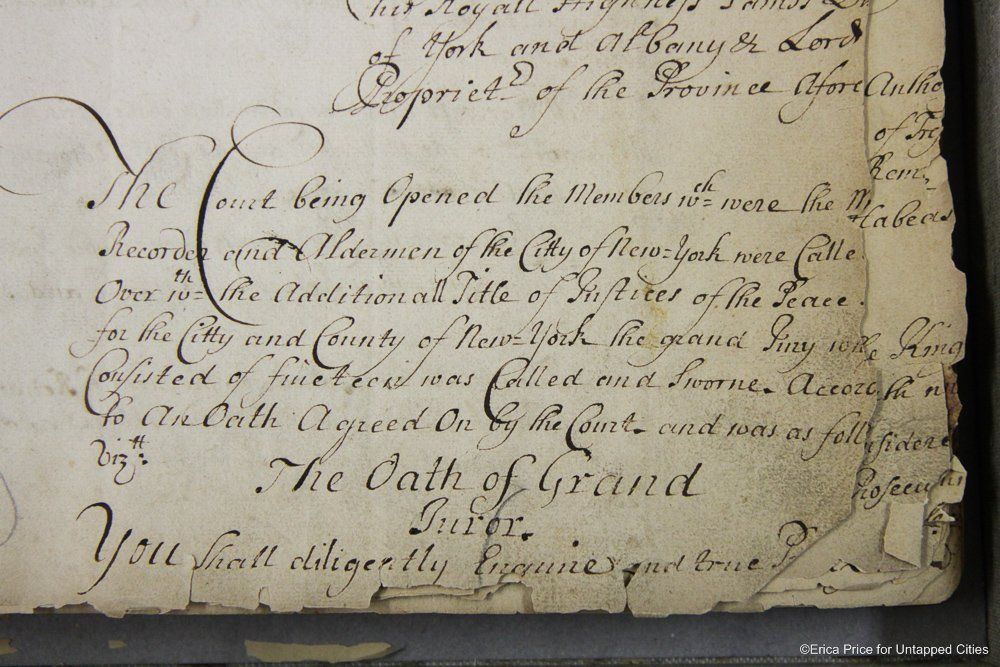

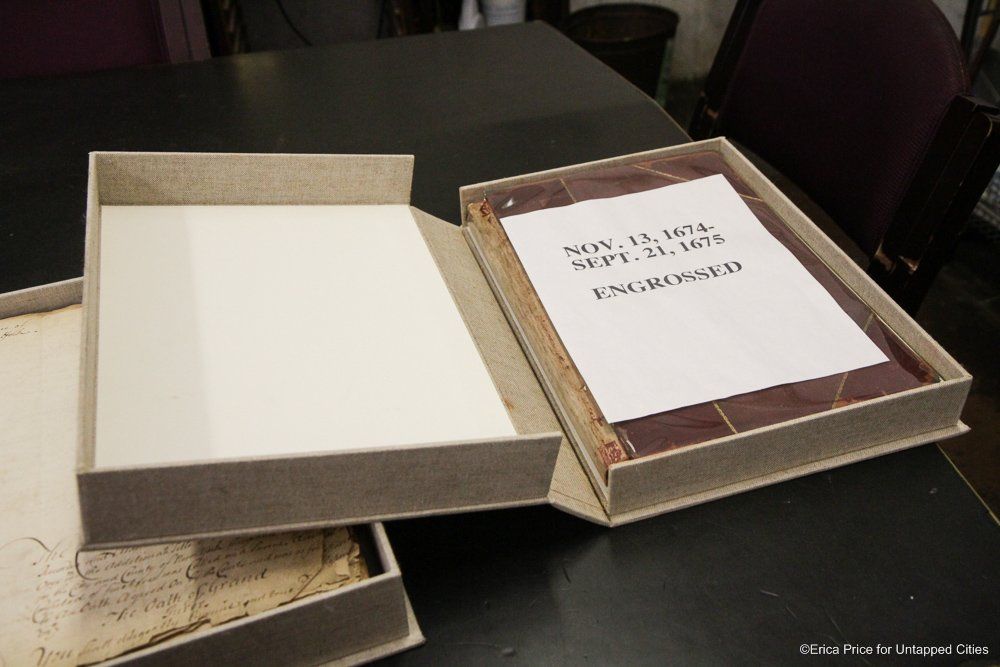

On another floor, are documents and books that have been archived carefully and placed into cases. One is the very oldest document in the archive, from 1674. It details the re-establishment of the English court, following the second surrender of New York from the Dutch to the English in February, 1674. One of the signers of the document coordinated this very surrender. Notably, this new document does not include Dutch signers, a reflection of the erosion of trust that resulted from the short, military re-takeover of New York which only lasted about six months.

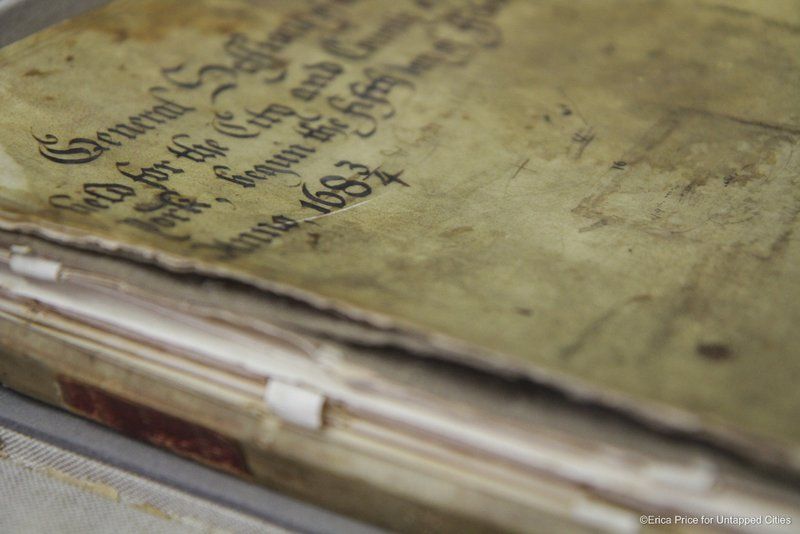

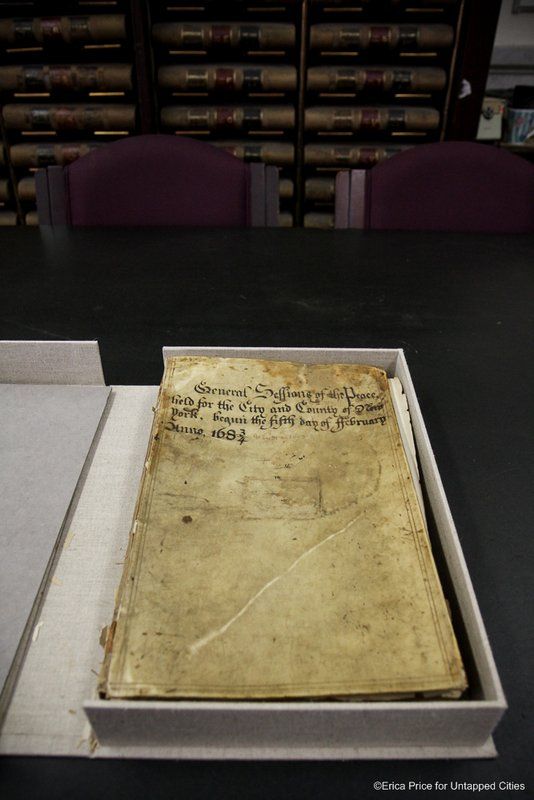

This 1684 book contains records from the general session of the court, including criminal cases and still has the original cover made of vellum, parchment made out of lambskin. The “fractional” year indicates a notation from the period when the way the years were written changed. For a period of time, both years were included.

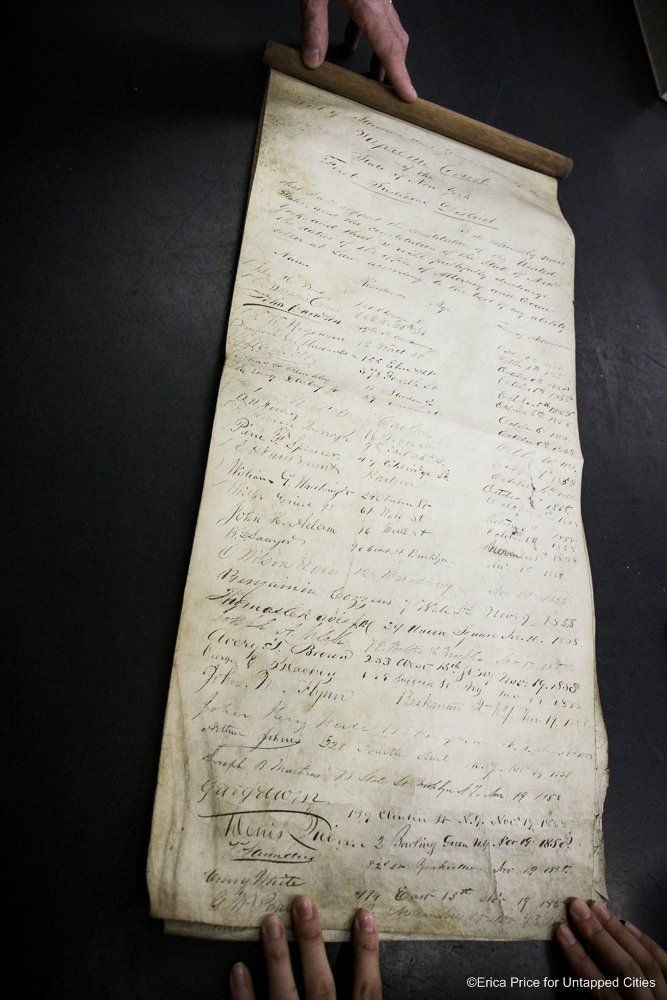

A very long parchment document shows the rolls of attorney, those admitted to the bar. The sheets were sewn together with a sewing machine, though previously a document like this would have been stitched together by hand. This one dates to 1865, at the end of the Civil War:

One room in the archives is of particular importance to the staff. It has been preserved for future generations, in the event the rooms on these archive floors are redone in the future, as more records are moved elsewhere. As van Nostrand says, the idea is to “leave it as a symbol of what it was like when it was first built. [There will be] one room not redone.” Here, the documents have been already removed for the most part but the layout, the Woodruff filing system, light sconces and more will remain intact.

And finally, as for whether the Division of Old Records is heaven to the archivists? Huth tells us, “Heaven is more organized to me. It might have the same contents, but it would be more organized.”

If you can’t get enough of this archive check out our slideshow of additional photographs and our Facebook live walkthrough of the space both below:

Next, discover the Top 10 Secrets of City Hall.

Subscribe to our newsletter