After-Hours Tour of the Fraunces Tavern Museum: "Path to Liberty"

Explore a new exhibit inside the oldest building in Manhattan, a witness to history throughout the Revolutionary War Era!

![Behind the Scenes Tour on the Queensway with the Trust for Public Land [Photos]](/content/images/size/w100/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/elevated_entrance-gateway-scaled.jpg)

As the chill winter weather begins to settle on New York City, an exciting project is heating up in Queens. Advocates for the rail to trail project The Queensway have had a string of recent victories, including a grant to design a portion of the trail as well as a nod of approval from The New York Times editorial board. At Untapped Cities, we’ve been following the project for the last three years and got a recent behind-the-scenes scoop of the Queensway, with a private tour by Andy Stone and the Trust for Public Land to highlight their goals and the next steps in the project.

The proposed Queensway is an abandoned, at times elevated and at times below grade railroad line that veers off the Long Island Rail Road (LIRR) tracks in Rego Park and shoots straight south to Ozone Park. We previously featured a video showing all 3.5 miles of the Queensway. The line was originally called the Rockaway Beach Branch, and was owned by the LIRR with service to the Rockaways.

After a fire in the 1950s on a bridge in the southern section, the line was truncated and a portion of the tracks were sold to the city to use on the IND Rockaway Line (now the A/C/E line). The northern portion became a stub and was taken out of service in 1962, a full 21 years earlier than when the High Line’s original rail lines were abandoned. Trackage, catenary wire hangers, and other equipment that was left behind is still there, some which date to 1908 when the line was electrified. Today, we’ll be taking you through four distinct sections of the Queensway.

We met our guide, Andy Stone of the Trust for Public Land (TPL), along with Nette Compton of TPL and some visiting landscape architects from Philadelphia at the Metropolitan Expeditionary Learning School in Forest Hills. As Stone pointed out, as the Queensway slices through Queens, its right of way passes through a diverse set of neighborhoods, from affluent Forest Hills to working class Ozone Park. Along the way there are numerous parks, park associations, and twelve schools within a five minute walk to the Queensway. Allowing students to walk to school or outdoor classroom excursions are some of the opportunities Mr. Stone believes The Queensway can support here.

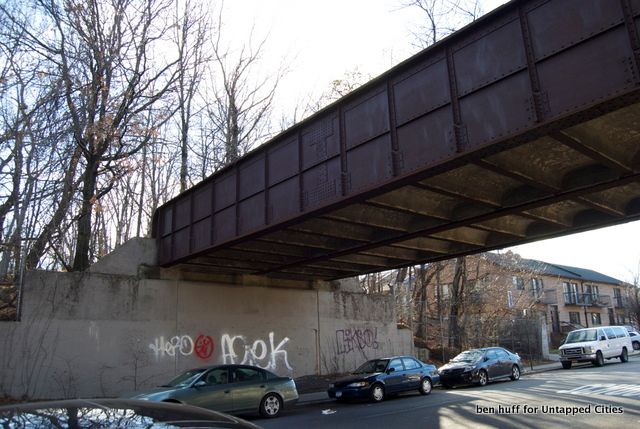

Adjacent to the school is a destroyed bridge where the abandoned rail lines cross over the a section of the LIRR. A small group of opponents of the Queensway have an alternate proposal which would return the right of way to an active rail line. This fallen bridge shows the difficulty of this option, promising an expensive proposal that would be years away from a transportation agency that has many unfunded capital projects. Although the city could sell the right of way to the MTA, the fact that it was once a rail line doesn’t mean returning it to active service will be an easy process.

Next we headed north to see the section that TPL believes is the most likely candidate for the first phase of the Queensway. Seperating Rego Park from Forest Hills, The Clearing abuts many residential and park properties, including a baseball field operated by Forest Hills Youth Activities, supporters of the project. This section just north of Fleet Street represents how the Queesnway can blend in and support the surrounding properties. Mr. Stone envisions those not playing baseball able to spend time exploring the woods adjacent to the fields.

Also, this is a portion of the trailway that is particularly wide, allowing for plantings of native species to help the local ecosystem. Our friends from Philadelphia (landscape architects by trade) pointed out that the trees here are not as stunted as trees growing on industrial brownfields often are, showing environmental remediation should be possible.

Rendering courtesy of The Friends of the Queensway

Probably the most exciting part of the tour was heading in to what TPL calls The Grove. The Grove is where the rail line dips below grade through Forest Park. Leaving our car we hopped a fence to explore below.

The Grove is easily the most traversable portion of the trail. Whereas the northern part was nearly impossible to walk through due to overgrowth, this section felt more like a recently abandoned rail line. Trespassing was clearly evident with graffiti covering most of the concrete in the area. Also different than other sections is the wider, valley-like feeling as the abandoned line blends in to Forest Park. The trail really opens up to the sky, and the current silence was a nice respite allowing us to retreat from the urban landscape above.

Friends of the Queensway and TPL are hoping for a win-win-win when designing the Queensway, a proposal that should satisfy both the little leaguers in Forest Hills to local business owners in Ozone Park. As a park, this right of way could connect neighborhoods in a way that they have not in years, and allow park goers to experience the sights, flavors, and sounds that make Queens the most diverse borough in New York City.

See renderings from a visioning competition for the Queensway and explore the Queensway in its current state through this video.

Subscribe to our newsletter