Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

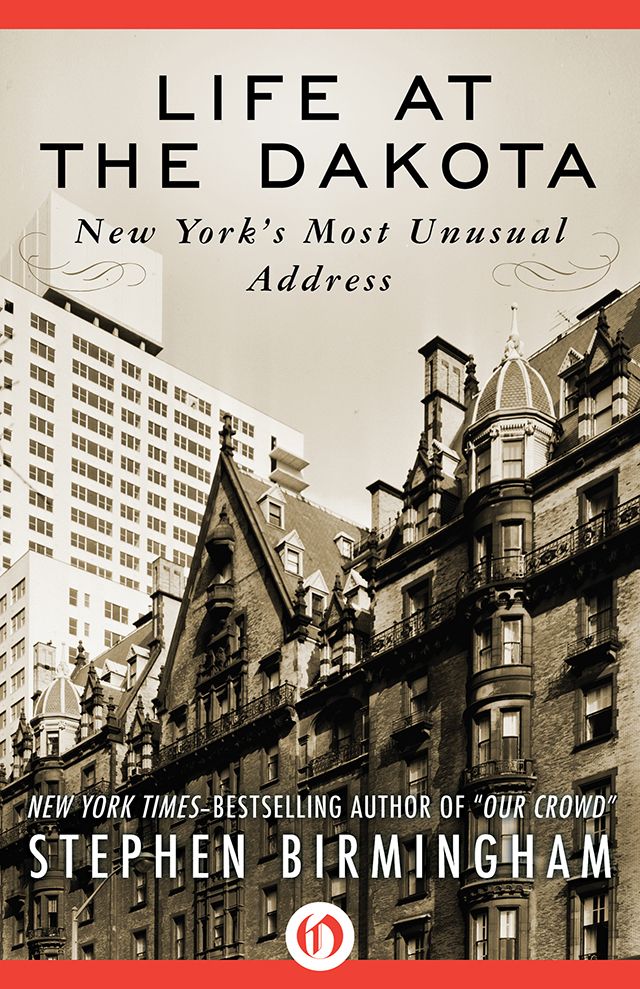

We are pleased to present an exclusive excerpt of the e-book Life At the Dakota: New York’s Most Unusual Address by Stephen Birmingham, the noted writer who passed away in November. His chronicle of the famed Dakota apartments in New York City differs from the recent book The Dakota: A History of the World’s Best-Known Apartment Building in offering precisely some of the “juicy details” that historian Andrew Alpern deliberately left out of his version. Life At the Dakota: New York’s Most Unusual Address can be purchased on Amazon, and enjoy the preview below.

The style of the Dakota’s architecture has been officially labeled German Renaissance. But it has also been called other things, such as Victorian Château, Victorian Kremlin, Brewery Brick, Pseudo-European and Middle European Post Office. In other words, to use a term much favored by architects, it is “eclectic.”

The architect whom Edward Clark chose to design his building, Henry Hardenbergh, went on to achieve a national reputation as a designer of elaborate hotels—among them the old Waldorf-Astoria and the Plaza in New York, the Willard in Washington and the Copley Plaza in Boston. In later years he would come to take himself with great seriousness. Described by a contemporary as “Napoleonic in stature,” he was diminutive, and to overcome this he took to placing his office desk and chair on a platform so that visitors would have to look up at him.

He was also quite voluble, and in a 1906 interview with Sadakichi Hartmann in The Architectural Record, Mr. Hartmann noted with some satisfaction that for every twenty words of questions, Mr. Hardenbergh would respond with two hundred words of answers. Mr. Hartmann commented on Hardenbergh’s “wiry” physique and his “shrewd eyes,” and also noted, “This man knows what he is about … I thought to myself, I am sure he deserves the reputation he has of having a roof on every house he builds,” meaning, perhaps, that Hardenbergh was known for completing every task he undertook. When Clark selected him in 1879, however, Hardenbergh was still relatively unknown, and quite young—only thirty-two. To an earlier interviewer, in 1883, when the Dakota was still unfinished, Hardenbergh confessed that he was “still trying to find himself.”

The Dakota from Central Park in 1895. Photo via Museum of the City of New York

Despite his youth, Henry Hardenbergh was most definitely a gentleman of the Old School and was descended from a New York family which had been among the city’s earliest settlers. The first Hardenbergh arrived in what was then the Dutch colony of Nieu Amsterdam in 1644, some three years before the arrival of Governor Peter Stuyvesant. Henry Hardenbergh’s great-great-grandfather, the Reverend Jacob Rutsen Hardenbergh, had been a founder of Rutgers College. After studying under the architect Detlef Lienau, considered one of the nineteenth-century masters of the German Renaissance and Beaux Arts styles, young Hardenbergh designed and supervised the construction of a library and chapel for his great-great-grandfather’s college. One of his first New York assignments was to design the Vancorlear Hotel, which used to stand at the corner of Seventh Avenue and Fifty-fifth Street. Though they were of different generations, and though Edward Clark and Henry Hardenbergh did not move in quite the same New York social circles, it was Hardenbergh’s grandiose execution of the Vancorlear that first drew him to Clark’s attention as an architect. The Vancorlear was a transient hotel that consisted only of suites. What Clark had in mind was an apartment house that would be run like a hotel. He hired Hardenbergh and told him, in effect, that the sky was the limit. Hardenbergh, sensing that this was to be his first important building—one that could make his reputation—decided to take a no-holds-barred approach.

Entrance Detail, 1965. Image via The Library of Congress.

What emerged from his drawing board was nothing if not ambitious. What Hardenbergh designed was essentially a huge, hollow cube, roughly as tall as it was long and wide. To this basic structure were added elaborate embellishments—ledges, balconies, decorative iron railings and tall columns of bay windows climbing eight stories high. A tall, iron-gated archway, flanked by iron planter urns provided the main carriage entrance from the Seventy-second Street side of the building and led into an H-shaped interior courtyard, designed as a carriage turnaround. In the center of the courtyard Hardenbergh placed two stone fountains, each spouting a dozen iron calla lilies. The courtyard led to a more modest arched entrance on the building’s Seventy-third Street side, which was planned as a servants’ entrance. (The building had not been open long, however, before servants complained that the Seventy-third Street entrance was not convenient. It was then decreed that this gate be kept permanently locked, to be opened only for funerals. Over the decades the “undertaker’s gate,” as it came to be known, has been opened about once a year.)

East Roof Detail, 1965. Image via The Library of Congress

The capstone of the building, however—the climax, the icing on the fantastic birthday cake—was the two-story-high roof, or, more accurately, succession of roofs. The Dakota’s roofs did indeed resemble a miniature European town of gables, turrets, pyramids, towers, peaks, wrought-iron fences, chimneys, finials and flagpoles. The roof was shingled in slate and trimmed with copper, and it was peppered with windows of every imaginable shape and size—dormer and flush, square, round and rectangular, big and small, wide and narrow. Nestled among all this, Hardenbergh designed a railed rooftop promenade with gazebos and pergolas and canopied sunshades. The courtyard below would also be circled with an awninged promenade.

The original specifications of the building called for “Suits [sic] of Apartments for fourty [sic] two families besides Janitors.” Hardenbergh had originally designed the interior space so that each of the seven main floors would contain six apartments, described in the building records as “French flats,” roughly the same in size and layout. But Edward Clark had begun renting apartments in his building-to-be to friends, acquaintances and other interested tenants long before the building was completed, thus giving future tenants the opportunity to select the size, variety and the number of rooms they needed. This meant that Harbenbergh’s floor plans for the building changed almost daily, as apartments were enlarged and divided to suit tenants’ wishes. Walls came down and doorways were created as the architect tried to fit individual apartments together like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle.

In the beginning he had planned to place the largest apartments on the lower two floors. This was because elevators were still something of a novelty and not entirely trusted (in contrast to today, when the higher the apartment is, the more desirable it is considered to be). Also, Hardenbergh reasoned that lower-floor living would seem more familiar to New Yorkers who were accustomed to living in town houses. The eighth and ninth floors were to be used exclusively as laundry rooms, service and storage rooms, and servants’ rooms. Then Hardenbergh hit upon the idea of turning the second floor into hotel-style guest rooms that could be rented to tenants to put up out-of-town friends. And in each of the four corners of the eighth floor he designed four smaller apartments. When Hardenbergh finally finished juggling rooms and spaces, there were sixty-five apartments in the Dakota, ranging in size from four to twenty rooms.

Image via Library of Congress

Scale and massiveness were stressed throughout the building. Many apartments had drawing rooms that measured 20 by 40 feet and bedrooms that were 20 by 20. In the sixth-floor apartment Hardenbergh designed for the owner (Clark thought he could popularize upper-floor living by putting himself near the top), was the building’s largest room—a ballroom-sized drawing room 24 feet wide and 49 feet long, with a fireplace at either end and ceilings graced by a pair of Baccarat crystal chandeliers. The Clark apartment also contained seventeen other “chambers.” Because Clark wanted floor-to-ceiling windows, these were given to all the other sixth-floor apartments to provide exterior symmetry.

In all the apartments wood-burning fireplaces abounded (the Clark apartment had seventeen), and in the beginning the fireplaces plus coal-burning stoves in the kitchens provided the building’s only heat. Wood and coal were delivered to the apartments daily, and the ashes from the fires of the day before were daily swept out. Gas was used only to light the chandeliers. Still under construction when the building opened was the subterranean boiler room beneath the lot next door, which would eventually provide steam heat and would also contain dynamos for generating “electric illumination.” Because he foresaw further development in the neighborhood, Clark specified that the Dakota’s boilers be big enough to supply heat to all the blocks from the north side of Seventieth Street to the south side of Seventy-fourth Street between Eighth and Columbus avenues. For his new neighborhood, Hardenbergh designed what amounted to a miniature Consolidated Edison, and for a number of years it served as just that.

Fence Detail, 1965. Image via The Library of Congress.

Hardenbergh’s plans specified that the foundation was to be laid on “solid rock,” and foundation walls were to be from three to four feet thick. The thickness of the exterior walls of the first floor was 24 to 28 inches, the second through fourth floor, 20 to 24 inches, the fifth and sixth floors, 16 to 20 inches, and above the sixth floor, 12 to 16 inches. The walls were tapered in this fashion to give them added strength. The floors themselves were three feet thick, arched and beamed and braced with brick and concrete. Between each layer of brick flooring, like a thick sandwich spread, was placed a layer of Central Park mud, which had been dug up in the park’s landscaping process—for soundproofing as well as fireproofing. Fireproofing was an obsession with Hardenbergh because, for aesthetic reasons, he wished to eschew fire escapes. All partitions within the building were of brick and fireproof blocks. The ceilings on the ground floor were fifteen and a half feet high. With each successive floor, ceilings were lowered imperceptibly until, on the eighth and ninth floors, where the help were to live, they were a mere twelve feet high.

East Facade Window Detail, 1965. Image via The Library of Congress

Over two hundred miles of plumbing were cemented into the thick walls of the Dakota to service the cast-iron wash basins, sinks and laundry tubs in the Dakotan kitchens. Bathroom fixtures were all of porcelain, including seven-foot-long bathtubs that crouched on claw-and-ball feet. In the beginning, however, bathrooms were in somewhat scant supply in Dakota apartments—again because Victorian sensibilities were involved. (Called water closets, they were considered unmentionable necessities.)

Though individual needs and whims of the Dakota’s first tenants played havoc with Mr. Hardenbergh’s original floor plans, some elements of his interior design remained that were innovative at the time and have since become almost standard in the layouts of luxury apartment houses. There was his “stem” system of elevators, for example. Each of the four passenger elevators—placed just inside the four corners of the courtyard—was designed to service two, or no more than three, apartments to a floor. Elevator lobbies were therefore small and intimate, creating a sense of privacy, eliminating the feeling of being in a building that housed more than two hundred other people—and also eliminating long, echoing corridors through which children would be fond of running. Apartment kitchens, meanwhile, opened out onto a similar system of four service elevators—a novelty in themselves in the 1880’s.

But for all the practicality of some of his ideas, it was in the area of purely frivolous and expensive ornamentation that Henry Hardenbergh’s heart clearly lay. By temperament he was more an interior and exterior decorator than an architect. He covered the Dakota with carved stone friezes and mullions, surrounded the outside dry moat with an elaborate iron fence adorned with the fierce, bearded heads of sea gods entwined with sea urchins with human faces. Inside were the carved marble mantels, no two of them alike, the carved plaster ceilings, the walls paneled with oak and mahogany, the heavy doors and over-doors and mortices with hardware of the heaviest solid brass. (In the Clark apartment doorknobs and plates and hinges were overlaid with sterling silver.) There were inlaid marble floors, wrought-iron staircases, walls wainscoted in rare marbles and choice hardwoods, bronze lamp fixtures and railings in the elevator lobbies. The elevators themselves were extraordinary examples of the millworker’s art— delicate, open cages of carved, spindled wood set in fanlike patterns.

Then there was the private dining room, designed to resemble an English baronial hall. The floors were of inlaid marble and the bases of the walls were of hand-carved English quartered oak. The upper portions of the walls were finished with bronze bas-relief work—designs of Indian heads, arrowheads and ears of corn—and the ceiling was also of hand-carved English oak. Dominating the room was a huge fireplace, big enough in which to hold a small party, made of Scotch brownstone and engraved with more Western symbols. In other words, the Dakota was built not only to last forever but to astound. A persistent rumor in the Dakota has it that one of the first tenants buried $30,000 in cash in the floor of his seventhfloor apartment. If true, the money reposes beneath the parquet of what is now John Lennon’s and Yoko Ono’s bedroom. It would cost at least $30,000 to dig up the bedroom floor, and besides, the Lennons don’t really need the money.

The thick walls and floors were designed not only to insulate the Dakota in winter and to keep it cool in summers when air conditioning was unheard of, but also to block out the city’s noises, dust and stench. Though the upper reaches of Eighth Avenue were still relatively quiet and soot-free, the Eighth Avenue streetcar rattled by, and it was assumed that the West Side would soon be as noisy and smelly as the rest of town. The Dakota was designed to protect its residents from all of that.

But one aspect of Henry Hardenbergh’s design—in a building that over the years has posed a number of riddles—remains a mystery. Though he covered the Dakota’s exterior with elaborate ornamentation on the north, east and south sides, he left the west face of the building absolutely blank and unadorned, as though when he got around to that side of the building, he had lost interest or run out of imagination. To be sure, the west side of the building could be regarded as the “back” of the Dakota. And yet this back side overlooked one of the building’s most gracious attractions—the private park with its clay tennis and grass croquet courts, an area of Dakota land roughly equal in size to the acre upon which the building stood.

In the building of New York brownstones it had become something of a tradition to leave the backs of buildings blank, and these were called “party” or alley walls because they usually faced an alley or an air shaft. But the Dakota’s back did not face an alley; it faced a garden. Is it possible that Hardenbergh anticipated the day when the Dakota’s back would indeed face an alley? That would not happen for eighty-five years, until, as we shall see, Louis Glickman entered the picture. Until then, the Dakota’a west-facing façade wore an embarrassed and unfinished look. From its own pretty garden, the Dakota looked truncated, as though Mr. Hardenbergh’s great château had been neatly and cleanly sawed in half.

Two events occurred in 1882, meanwhile, when the building was only half completed, which affected its history profoundly. The first was the official renaming of Eighth Avenue as Central Park West. This was an indication that the city, too, had faith in the expansion of the West Side, and it gave Mr. Clark’s building a somewhat prettier address. The second was the sudden death, of a heart attack, of Edward Clark at the age of seventy-one. When he heard this news, Henry Hardenbergh was dumbstruck. What would become of the project now? For several anxious weeks Hardenbergh worriedly waited to hear whether or not Clark’s heirs would call the costly effort off. He spent his time characteristically— designing Corinthian columns to embellish the old Third Avenue trolley-car barns. He was, however, eventually reassured that the building was to continue as planned.

For more, Life At the Dakota: New York’s Most Unusual Address can be purchased on Amazon, and get more information about the book at Open Road Media. Next, read about the Top 10 Secrets of the Dakota

Subscribe to our newsletter