The New York City subway officially opened in October 1904 with the Interborough Rapid Transit (IRT) line, which initially ran from City Hall Station to 145th Street in Manhattan. Brooklyn was the second borough to be connected to the IRT in 1908, so it’s no surprise that the Brooklyn subway system holds its fair share of secrets. Read on for the top ten secrets of the Brooklyn subway, from the location of the MTA’s former money room to a tribute to Aretha Franklin and other artworks hidden in plain sight.

Uncover more secrets, and visit some of the sites mentioned in this list on Untapped New York’s upcoming Underground Brooklyn Subway Walking Tour!

1. Secret Tunnels to the Former MTA Money Room

From 1951 to 2006, the New York City transit system ran an armored train that moved all the subway and bus fares collected to a secret room, the Department of Revenue’s Money Room, inside a 13-story building at 370 Jay Street in Brooklyn. 370 Jay Street was strategically located atop a subway station where, according to information from a previous New York Transit Museum exhibit, “tunnels could be built to connect the building to IND, BMT and IRT lines.”

A crashgate along the Jay Street southbound F line subway track allowed the fares to be unloaded directly into the basement of the building that looks like a uniform government building, but has secret tunnels inside.. In the photo above, you can see the crashgate as seen from the Jay Street F line. There was also a crashgate on the northbound R train track at the Lawrence Street station (now Jay Street Metro-Tech).

After the money was collected from the train, and taken through one of the crashgates, it was brought down an empty tunnel to one of two revenue-only elevators that carried it up to the money room on the second floor. The money room contained a vault within a fortified cage and many security cameras that tracked the movements of employees (who all wore special pocketless clothes). The Money Room closed January 2006.

2. A Fake Townhouse Hides Brooklyn Subway Infrastructure

Strolling past the row of houses on Joralemon Street in beautiful Brooklyn Heights, you might notice that something is a little off. Take a close look at the red brick brownstone at number 58; the windows, you’ll see, are completely black. Suspicious, isn’t it? As it turns out, building number 58 is not what it seems; it is a fake brownstone, behind which lies a hidden subway ventilator. It may also function as an emergency exit, but the MTA does not release those locations for safety reasons. Read more about this and other fake townhouses here.

What would it be like to live next to an active subway ventilator, you might wonder? Judy Scofield Miller, who lives next door to the fake brownstone at number 58 with her husband and two kids, says they have grown accustomed to the buzz and hum of whirling ventilator blades that disrupt their quiet living room every few weeks (Daily News). The fake brownstone on Joralemon Street is also rumored to serve as a secret passageway to the 4/5 trains running in the tunnel below.

3. MassTransitScope in the Abandoned Myrtle Ave Subway Station

This art installation by MTA Arts for Transit is one of our favorite reuses of an abandoned station. Closed in 1956, Myrtle Ave subway station used to run on the Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit line between Manhattan Bridge and DeKalb Avenue. The DeKalb Ave section ran into a lot of problems as it was the chokepoint for the entire BMT Broadway subway operation, “with a lot of merges and some routings crossing others at grade in the switches on both sides of the station,” writes Joseph Brennan.

The entire area was rebuilt in 1956, and this caused Myrtle Ave to lose its southbound platform. The northbound platform still exists but has been closed ever since. An artwork called Masstransitscope by Bill Brand is located in the abandoned Myrtle Ave station. Installed in 1980, the piece works like a giant zoetrope. The piece was restored in 2008 and 2013.

4. The Underbelly Project’s Secret Brooklyn Subway Art Exhibit

Underneath Williamsburg at South 4th Street there’s a 6-track station of the IND line that was never opened. In 2009, over the course of a year, street artists PAC and Workhorse invited 100 street artists create art inside and outside of the station overnight. Dubbed The Underbelly Project, the idea was to create an underground gallery, but as PAC describes, apart from recruiting artists they could trust from pre-existing relationships, everything “happened organically along the way.”

The project went on to be replicated in Paris. Whether the art still exists in the Brooklyn subway station remains a mystery, but most we’ve spoken to feel that the MTA sealed off the station and it has remained relatively untouched. Second Avenue Sagas has a great explanation of the unused subway station.

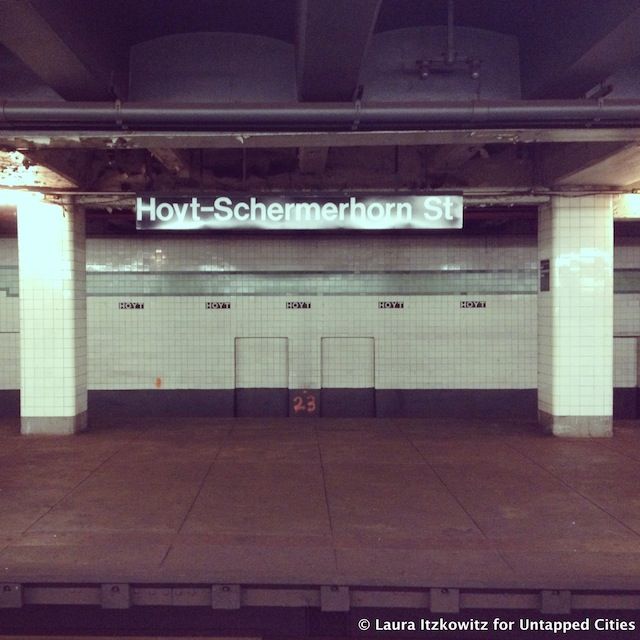

5. Michael Jackson Filmed “Bad” at Hoyt-Schermerhorn

There are few identifying details in the 1987 music video for Michael Jackson’s song “Bad,” but it’s a little-known fact that it was shot in the mezzanine of the Hoyt-Schermerhorn subway station in Brooklyn. The full-length video is 18 minutes long and was directed by Martin Scorsese, whose picture appears in a Wanted poster in the subway station.

According to IMDB, the choreography is inspired by the dance sequence for the song “Cool” in West Side Story. Jackson was apparently a huge fan of the movie version of the Broadway musical by Stephen Sondheim, Leonard Bernstein, and Arthur Laurents. The story behind the video was inspired by Edmund Perry, a Black honors student shot by a plainclothes police officer after allegedly trying to mug him in Morningside Heights. The 1985 tragedy caused a media sensation.

6. Commuter Banking at Borough Hall

Most straphangers who pass through the Brooklyn Borough Hall subway station barely notice the two darkened windows that are set within the blue tiling on the upper level of the station. But look carefully and you will see the faded words “COMMUTER BANKING” at the top. On the lower part of the window, the hours are still visible: “MONDAY THROUGH THURSDAY 8 A.M. TO 6 P.M.” as well as a small yellowed button that would have summoned the teller.

These commuter banking windows, made by Diebold Incorporated out in Ohio, were once run by the Brooklyn Savings Bank, at least through the late 1960s and likely through the 1980s until the bank closed. The Brooklyn Savings Bank was founded in 1827, operating in multiple headquarters over time in Brooklyn Heights. Its most architecturally notable and longest standing headquarters was at Clinton and Pierrepoint Streets, designed in a Neoclassical revival style around the time of the World’s Colombian Exhibition in Chicago. The granite for the building was quarried from Maine.

The Brooklyn Savings Bank would be located here from 1894 to 1961, when it moved to Montague and Fulton Streets. Based on the design and architecture of the banking windows and surrounding tiling, it is likely that the subterranean initiative was installed around the same time the bank moved to its new location in the new “Brooklyn Civic Center” area.

7. The Abandoned Platform at the Nevins Street Brooklyn Subway Station

As the New York City subway system expanded and changed, some stations and platforms were rendered obsolete or combined into new forms. If you look closely enough, you’ll start to see the patchwork updates that close off the former structures from view.

There’s the famous City Hall subway station that was decommissioned because its curved track could no longer accommodate new, longer trains. Then there are the abandoned platforms underneath 42nd Street A/C/E that once accommodated the special Aqueduct Racetrack train, Nevins Street and Bergen Street in Brooklyn.

8. The World’s Highest Rapid Transit Station is in Brooklyn

The highest subway station is at Smith and 9th Street in Brooklyn, located 88 feet above street level, according to the MTA. It’s not just the highest subway station in New York City, but it also holds the distinction of being the highest rapid transit station in the world. It’s a stop for the F and G trains.

The station was originally built as part of the IND network in 1933. According to Atlas Obscura, “The original plan was to tunnel under the Gowanus Canal, but that proved too expensive so a viaduct was constructed instead. The station needed to be high enough to fit over the Ninth Street Bridge, a vertical lift bridge that had to be elevated enough to allow tall-masted ships to pass underneath when raised.” Smith and 9th Street also has some fun nautical chart art on all of its windows.

9. Artwork Hidden in Plain Sight at the Atlantic Avenue-Barclays Center Station

The subway entrance above Brooklyn’s Atlantic Avenue-Barclays Center station has a secret wellspring of life inside: an installation called Line (Sea House) by the artist George Trakas, commissioned by MTA Arts & Design, and created in collaboration with diDomenico and Partners in 2004 that takes up the entire original Beaux-arts fare control center. The project used artistic vision, architectural experience, and the space’s unique potential in order to create a more pleasurable and aesthetically pleasing transit experience. Trakas and the architects worked together to create a a plaza, skylight, staircase, and corridor made of limestone, brushed steel, and granite, and Trakas designed a massive steel boat-like structure that sways high above the ocean of travelers beneath.

From inside the above-ground kiosk, visitors can look through a peephole equipped with a lens to see the boat-shaped contraption made of stainless steel hanging just underneath the glass, as well as a granite wave that crests at the meeting place between the passageways that link Atlantic Avenue and Pacific Street.

10. There’s a Tribute to Aretha Franklin at Franklin Ave

In response to Aretha Franklin’s passing in August of 2018, a bunch of New Yorkers took it upon themselves to create tributes to her at Franklin Avenue subway stations in Manhattan and Brooklyn. The DIY memorials, which included signs that read “Respect,” the name “Aretha” spray painted next to “FRANKLIN,” and signs with lyrics from her songs, were removed by the MTA within a day. In their place, the MTA installed black signs with the word “Respect” above every FRANKLIN AVE. tiling inside the station at Fulton Street along the Bedford-Stuyvesant/Crown Heights border in Brooklyn. With a “Respect” sign over every station identifier on both platforms, there are about twelve of the tributes total. There are also large “Respect” signs inside the Franklin Street Station in Manhattan. These signs created a permanent memorial for the legendary singer.

The signs were designed as a partnership between MTA Arts & Design and LeRoy McCarthy of Heterodoxx INC. McCarthy was responsible for the first spray painted tributes at this same station when Franklin’s death was announced. The MTA, via a spokesperson, said in a statement that “We wanted to memorialize the outpouring of love from the community for Aretha Franklin and in consultation with local leaders, we agreed that ‘respect’ was a beautiful tribute and worthy message.”

Extra secret: The particular colored tiling at the Franklin Ave station is specific to the IND line and part of a color-coded system devised by chief architect of the New York City subway system, Squire J. Vickers.

Brooklyn Subway Tour

Ride through some of the Brooklyn subway system’s abandoned stations and uncover more secrets on our upcoming Underground Brooklyn Subway Walking Tour!

Michelle Young, Laura Itzkowitz, Justin Rivers, and Matt Litwack contributed reporting for this article.

Next, read about the top 20 secrets of the NYC subway!