Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

In 2015, artist Ingrid Burrington released a handy illustrated pocket guide to the cryptic symbols you see spray painted on the city’s streets. She raised money for its publication on Kickstarter (our team eagerly bought a copy) and the attention over the project led to a new edition under Melville House Publishing, titled Networks of New York: An Illustrated Field Guide to Urban Internet Infrastructure which was just released on August 30th.

Most people ignore these practical markers, written in a language unintended for the general public. But Burrington started unpacking the code by beginning with a much larger question: “What does the Internet look like?” She shows that you don’t need hacker computer skills or fancy devices to reveal the hidden infrastructure of the online world – you just need to look down at the ground, up at buildings and sometimes, right in front of you. She calls this “practicing the everyday magic if seeing the Internet as part of the city’s landscape and every day life.”

Just before the book was released, we took a walk with Burrington in Manhattan to really get a sense of how her viewpoint of the city works. Here are some of the fun things we discovered, starting at the Google headquarters at 111 8th Avenue – the super block of a building between 8th and 9th Avenue and 15th and 16th Street.

The building was first constructed in 1932 as the Port Authority Commerce/Union Inland #1 Building, which had quite a bit of business connected to the waterfront shipping industry along the West side, and was later used as a carrier hotel by Taconic Investment Partners, which bought the building in in 1998. Google bought the building for $1.8 billion in 2010.

Burrington likes to start her walks at the Google headquarters because of its history in telecommunications and its subsequent relationship to the buildings around it– which means the symbols are literally “coming out of the building,” says Burrington excitedly on our walk. She’s the type that will get a “weird delight out of nice samples” of the symbols, she says as we peer into a sidewalk grate and and begin to get curious looks from bystanders.

Indeed, on the sidewalk, extending from the building walls, you can see fresh symbols that denote the telecommunication lines for AT&T, Sprint, RCN and Time Warner. FOC means fiber optic cable. Shallow cover means quite literally that quite close to the surface there are a bunch of lines – a warning to those doing roadwork to beware.

Burrington checking out new some symbols

Burrington points out the long attachment atop the light post at the intersection of 16th Street and 8th Avenue, which is part of what’s known as a “Distributive Antenna System.” These devices are akin to cell repeaters and address the urban canyon effect– when telecommunication signals can’t reach certain areas because of the density or height of the buildings nearby.

The antenna and a rectangular box attached to this light post help “bounce” or reroute a lower level signal. Sometimes, a spray painted marking will come out of a light post to denote the wiring related to this system. The company Crown Castle operates the antenna system, having bought up two other companies that previously were in operation. As we’ll come to see on the walk, this is a typical acquisition story in the telecommunications world.

We then hopped into the subway to head down to the AT&T Long Distance Building and the Western Union Buildings, two architectural landmarks of the telecommunications industry. The AT&T building, built in 1932, features a lobby which stands as a testament to the technology of the telephone. There are grand symbols on the ceiling laid out in mosaics and a tiled map of the world proclaiming that “Telephone Wires and Radio Unite to Make Neighbors of Nations.” The map is a throwback to an earlier geopolitical era – Africa and Eastern Europe have far different internal borders. There’s also a solo trans Atlantic ocean liner pictured, nowhere near scale. AT&T still operates in this building and it’s another hotspot for street symbols.

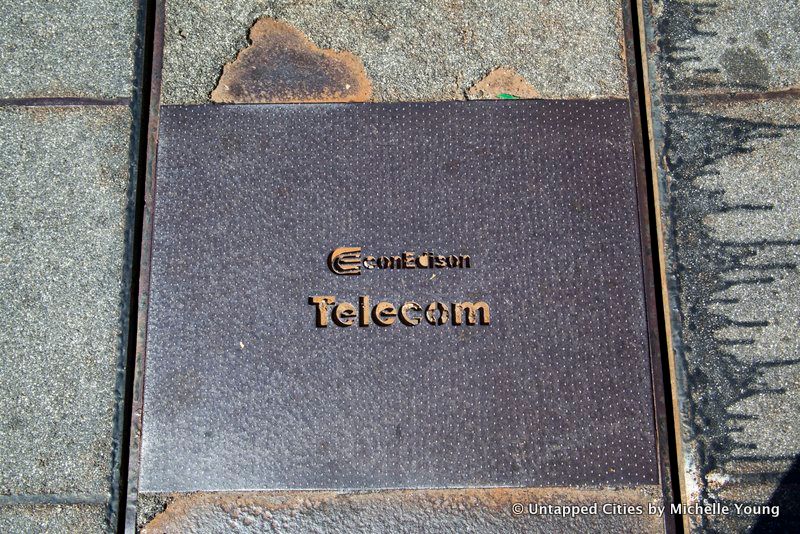

Manhole covers also abound nearby, which are another subject of Burrington’s book. Manhole covers often remain long after companies are swallowed up by other ones or go out of business. The ConEd Telecom manholes just outside the AT&T building are remnants of a parallel fiber network built by ConEd that “didn’t really work,” she says, “ConEd resold the network to RCN Metro Network division, which eventually became Lighttower [Fiber Networks].” Another example of the mergers and acquisitions within the industry.

Sometimes you’ll see a cluster of certain types of manhole covers, which we came across along Hudson Street, which are giveaways for potentially deep and complex telecommunications operations below ground. The manholes here contain the letters ECS, Empire City Subway, formed after the Great Blizzard of 1888 which took down much of the city’s overhead electrical infrastructure. ECS was created with a mandate to build underground ducts for telecommunication services in Manhattan and the Bronx and later became majority owned by Bell. The New York Telephone Company was responsible for the other boroughs.

Today, Empire City Subway exists as a subsidiary under Verizon and the New York Telephone Company became a company called Verizon New York – “so technically you have to go through Verizon to put any new fiberoptic cable underground in New York City,” says Burrington. Underground, the ducts get pretty crowded and there’s a battle between operators for space – just like there is above ground in the world of real estate. In fact, dead wires are often left there to prevent other companies from taking the space.

An ECS Subway manhole on Hudson Street

The Western Union Telegraph Building at 60 Hudson Street is within eyesight distance of the AT&T Building. Built around the same time as the AT&T Building,60 Hudson Street has conduits that connect the two buildings underground because there was once a significant amount of shared business between the two companies. The connections here have influenced the more recent transformation of 60 Hudson Street into a carrier hotel.

Companies rent space at 60 Hudson Street, run their cables underground, and access the network in the AT&T Building – a “convenient hack,” describes Burrington, “without having to negotiate anything with AT&T.” There’s a rumor that the first location that overseas signals travel after arriving in the New York City region is 60 Hudson Street, making it a major switching point. There’s also clearly some kind of project going on that requires a significant amount of resources, as there are two mobile generators parked alongside 60 Hudson Street and cables running literally into and out of openings in the building.

Here at 60 Hudson Street, all the overlap in companies somewhat but not fully explains the fact that AT&T has conveniently taken ConEd and Hugh Okane traffic cones and spray painted AT&T on them!

Burrington also points out other objects on the streets we ordinarily just walk by. Atop the green traffic control boxes that are attached to lamp posts, you may see a small semi-spherical attachment. This is a wireless router which was part of the NYCWiN (New York City Wireless Network), funded by Department of Homeland Security money to build out a city-wide emergency services broadband wireless network.

In theory, all the city agencies would communicate within this network. It launched in 2009, and was built out by Northrup Grumman, but by 2011 the initiative was determined to be a flop. The funds needed for maintenance and upkeep were simply not in line with the actual use. The network is still in operation, primarily used Department of Environmental Protection for monitoring water meters and the Department of Transportation for traffic studies.

Within the Canal Street A/C/E stop, we come across the box where the radio frequency symbols of the subway’s wireless network hangs – Burrington notes the “X” and orange spray painted that denoted to workers where the box should be installed. We also come across the a manhole on the subway platform at 14th Street which stumps us both – but now we’re seeing them everywhere in the subway system, just like the spray painted symbols on the street.

Get the book Networks of New York: An Illustrated Field Guide to Urban Internet Infrastructure on Amazon.

Apprpriately, we actually uploaded the photographs for this article in the New York City subway this morning using TransitWirelessWifi. It was pretty speedy, when in the stations.

Subscribe to our newsletter