Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

Coney Island is one of New York City’s gems, appearing front and center on advertisements, brochures, and guides. For more than a century, the famed destination at the southern tip of Brooklyn has brought in tourists from all over the world to ride the Cyclone, take in views of Brooklyn from the Wonder Wheel, and have a bite of a Nathan’s Famous hot dog. Many of Coney Island’s historic structures still remain, some from the late 1800s when Coney Island developed as the nation’s foremost amusement destination. Coney’s Island Riegelmann Boardwalk, which may soon be changed from wood to plastic, was constructed in 1922 and 1923.

But over the years, Coney Island’s look has changed significantly, and lesser-known occurrences such as fires altered the landscape. There were over a dozen major fires throughout Coney Island’s history, including five in the 1890s when the three competing amusement parks—Luna Park, Dreamland, and Steeplechase Park—began being planned and constructed. Steeplechase Park was partially burned down in 1907, while Dreamland dealt with a major fire in 1911.

Perhaps the most destructive fire took place in 1932, when 40-mile-per-hour winds drove a fire that burned four square blocks and resulted in $5 million in damages. The wooden boardwalk also faced numerous fires shortly after it was constructed, and half of Luna Park was destroyed in 1944. Two such fires in 1939 took a major toll on Coney Island’s boardwalk and Steeplechase Park, and a series of photographs that NYC Parks shared with Untapped New York showcase some structures just days before their eradication.

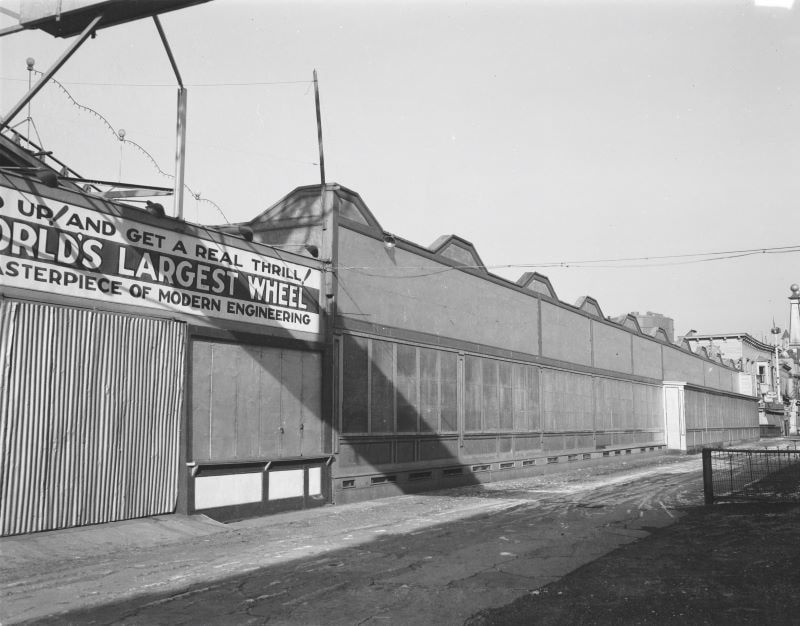

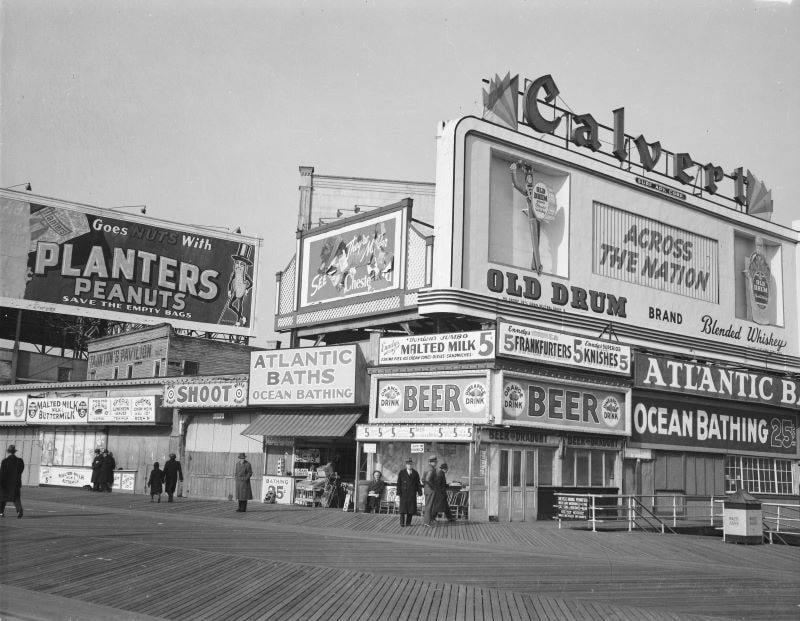

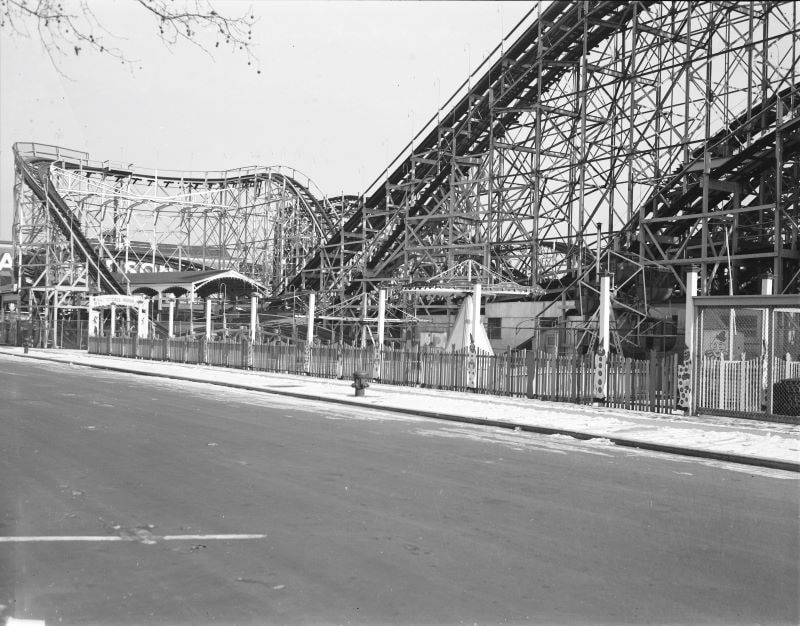

The Demolition Series consists of 223 images that were taken by the NYC Parks Department Photo Unit on January 6 and 7, 1940. According to Rebekah Burgess, Photo Archivist with NYC Parks, the images survey the damage from two consecutive fires in 1939 that damaged or destroyed much of Steeplechase, the surrounding boardwalk, and a number of bathhouses, concessions, and amusements.

According to the book Coney Island Lost and Found, “The amusement area boasted sixty bathhouses, thirteen carousels, eleven roller coasters, two hundred restaurants, and more than five hundred small businesses. Perhaps the most symbolic change during the 1930s was the rise of Nathan’s Famous and the decline of Feltman’s Restaurant. Nathan’s was a nickel ‘grab-joint’ and Feltman’s was a sit-down restaurant with tablecloths. Cheap thrills were replacing the refined entertainment proposals of the 1920s. Slideshows and strip joints became popular forms of entertainment.”

NYC Parks Commissioner Robert Moses was already pushing to expand the boardwalk and beach as part of a $3,200,000 Coney Island Improvement project that would open 24 acres of the new beach area, widen the narrow beach to 500 feet, straighten the wooden boardwalk, realign Surf Avenue, and get rid of the riff raffy establishments that had taken over in the 1930s. These fires were the perfect excuse for Moses to push many of these changes to go through. He ordered a survey organized geographically by Tax Lot to itemize and quantify the accrued damage. After this, on January 22, bulldozers began demolition on the Municipal Baths and the damaged boardwalk.

Moses’s takeover began with a November 30, 1937 report called The Improvement of Coney Island, Rockaway and South Beaches, in which he proposed radical changes that would fix much of Coney Island’s “sad commentary on the lack of foresight of the citizens.” Moses complained that the boardwalk was constructed too near the water, little land was in public ownership, it was way too crowded, and there was no strict enforcement of ordinances and rules.

As one of his first acts in 1938, he banned new advertising along the Boardwalk, banned loudspeakers near the beach, and put up very explicit signs with rules and regulations. He then tried to realign the Boardwalk between Stillwell Avenue and Ocean Parkway. The Boardwalk was relocated inland and extended to the border of Manhattan Beach, which proved damaging to the amusement area. He further intimidated property owners as a way of planning a playground and Parks Department headquarters, later announcing plans to move the New York Aquarium to Coney Island’s old Dreamland site after Mayor La Guardia vetoed his decision to move it to the Bronx Zoo. Years later, he set up the destruction of Coney Island’s West End as part of an urban renewal project.

These are the last extant views, both interior and exterior, of many older buildings and businesses along the boardwalk:

Next, check out 27 Secrets of Coney Island!

Subscribe to our newsletter