A Salvaged Banksy Mural is Now on View in NYC

This unique Banksy mural goes up for auction on May 21st in NYC!

The architect who designed Lever House and Manhattan House, two of New York’s most highly regarded mid-twentieth century buildings, also designed the lesser-known Sedgwick Houses, a public housing project in the Bronx. The Sedgwick Houses development is also an example of innovative Modernist architecture, but as with Lever House and Manhattan House, it proved difficult to replicate successfully.

Gordon Bunshaft of Skidmore Owings & Merrill designed Lever House, at 390 Park Avenue in Midtown Manhattan, one of New York’s first International Style glass curtain wall “slab” office buildings with a public plaza. It was completed in 1952 and is credited with being one of the key catalysts for ushering in a new era of commercial architecture.

Lever House, built 1952.

Lever House, built 1952.

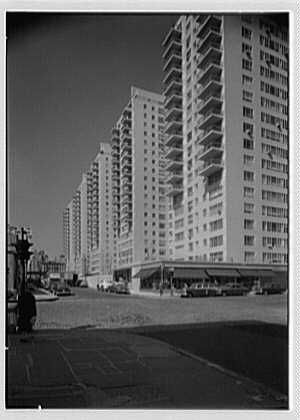

Similarly, Bunshaft’s Manhattan House, a luxury apartment building built in 1950 on the Upper East Side at 200 East 66th Street, is celebrated as one of the City’s first and best Modernist apartment houses with its unornamented facade of light color brick.

Manhattan House, built 1950. Photo (1952) via Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division by Gottscho-Schleisner, Inc.

However, as the Landmarks Preservation Commission designation report observed, “Lever House spawned a host of imitators but has been rarely equaled.” As for Manhattan House, the Wall Street Journal noted that it was “the mother of many lesser imitators.”

On the other hand, the Sedgwick Houses, a 7-building public housing complex in the Morris Heights section of the Bronx, is a mostly forgotten part of Bunshaft’s portfolio. Low income housing in the Bronx does not have the same cachet or visibility as trophy office buildings and luxury apartment houses in Manhattan.

The Sedgwick Houses project was one of the first Modern style public housing complexes of rectangular-shaped red brick buildings with a towers in the park layout. Bunshaft was inspired by the ideas of Le Corbusier, the Swiss-French architect and theorist.

Though taller and larger than the surrounding buildings, the Sedgwick Houses are part of the neighborhood and not an enclave entirely separated from it. Some of the buildings face onto the bounding streets, albeit at angles, creating a visual and physical connection to the City around it. Also, the site’s superblock is broken up by extending some roadways into it from the street grid.

In addition, the Sedgwick Houses complex relates well to its site. To their credit, Bunshaft and the New York City Housing Authority retained the sloping topography, which balances the sparse architecture. They also created a park that provides a buffer adjacent to the Cross-Bronx Expressway, which passed by in a cut to the south.

Sidewalk sheds are in place due to ongoing repair work

To be sure, good design does not solve all of the problems facing public housing and its residents; the Sedgwick Houses has had problems with crime and tenants have charged that neglect has created problems including leaky roofs.

Similar to the imitators of Lever House and Manhattan House, many of the public housing projects that followed the Sedgwick Houses’ example did not execute the concept nearly as well and in some cases were such abject failures that they were abandoned and demolished. Gordon Bunshaft left an impressive architectural legacy but it turned out to be more unique than universal.

NOT THE BIRTHPLACE OF HIP HOP: The Sedgwick Houses are sometime incorrectly described as the “birthplace of hip hop.” That honor goes to the similarly named General Sedgwick House located nearby at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue, where Clive Campbell, better known as DJ Kool Herc, created break-beats at a party in 1973.

Next, read about 5 urban planning projects that will change the Bronx and the Brutalist Orange County Government Center in Goshen, NY.

Subscribe to our newsletter