Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

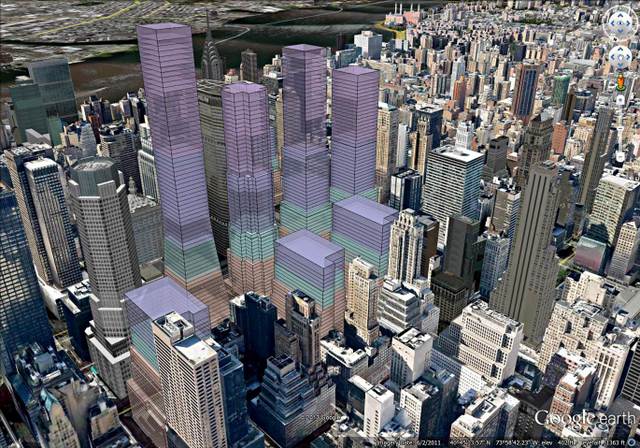

A transportation planner, a historic preservationist and an architecture critic walk into an auditorium. That’s not the start of a bad joke, but a recent attempt by Columbia University’s Center for Urban Real Estate to spark a spicy debate about the merits and demerits of the proposed Midtown East rezoning. Spearheaded by the Department of City Planning, the plan aims to upzone a 73-block area around Grand Central Terminal to accommodate more, larger office towers. If successful, the rezone will be the last of the Bloomberg administration’s long record of zoning changes; since 2002, 37% of the city’s 300 square miles have been rezoned.

But somewhat surprisingly, there wasn’t much to debate that night – those who weren’t outright opposed to the plan were quick to point out its flaws. Michael Bloomberg leaves office in December, and some accuse him of trying to push through this last rezone as a sort of half-baked cherry on top of a grand 12-year urban planning agenda. Others call the rezone a gift to the mayor’s big-wig developer friends. Whatever their gripe or their stripe, all the speakers seemed to agree that some things in this city are worth fighting for – rezone or not.

New York City business leaders often complain that the city’s strict preservation laws and the limited availability of land for development will inevitably hamper New York’s ability to compete with other established world cities like London or emerging ones like Shanghai. Defenders of the rezone see it as an attempt to encourage newer commercial space in the most important commercial center in New York, if it is to retain its place in the global economy.

But preservationists counter that is too simplistic an argument. Some midtown buildings are obsolete but not all. Owners have invested in upgrades of their own volition. What’s more, Midtown East and other New York neighborhoods are made great by the juxtaposition of old and new, brick and stone, glass and metal, big and small, they say. This is why people want to spend time outdoors here, not in car-centric Shanghai or London’s spit-shined Canary Wharf. Andrew Dolkart, director of Columbia’s historic preservation program, wants a plan that isn’t just trying to compete with Shanghai. “We need a new New York City,” he says, “not a recreation of the banal office districts of other cities.”

The needs of office users are changing however, and firms’ relationships with the city are changing, says David King, assistant professor of urban planning. Young tech firms – the kind Bloomberg and others are desperate to attract – are choosing to locate in refurbished old buildings surrounded by transit and amenities like cafes and bars. Google chose Chelsea for these things, and they form a big part of what makes New York appealing, not just for firms, but for the new generation of workers they rely on. There are of course firms that will always prefer big CBD office blocks, but preservationists and latte-sipping coders alike point to New York’s active street-life as an existing, enviable leg up over other world capitals.

Preservation advocates have been the most critical of the midtown rezone, but Dolkart asserts he is not opposed to new development. Publicity on the Midtown East rezone has set up a simplistic dichotomy – landmarks vs. new development. But it is a false dichotomy, he says. Preservationists are worried about losing those things that make New York so desirable. They also want new, quality architecture. There are architecturally significant buildings in the neighborhood that have not been landmarked but some supporters of the plan claim there is not one unprotected building worthy of landmark status. Meanwhile, major redevelopment and modernization are already occurring in the area without the rezoning. But Kate Ascher, a real estate consultant, author of The Works, and a professor at Columbia’s real estate development program, says the idea that all these buildings are just going to “mushroom up” is unrealistic and just not really the way real estate works. “They will come when they’re ready,” she thinks, and even Bloomberg expects only a few new buildings to result from the upzoning.

Ascher’s primary concern is that new buildings will arrive before the support infrastructure is ready to meet them. No infrastructure is proposed before these new skyscrapers come up. She thinks financing will be the principle hurdle for the rezone. New York City has in the past been good at finding new ways to finance capital improvements, and Ascher trusts the city’s planners to work to get those public realm amenities ready. Value capture, the capturing of the value of redevelopment to pay for infrastructure later, has become a popular method of financing large transit improvements. But property values, especially in New York City, are correlated to the value of existing infrastructure, so there is a risk that added value won’t be enough to afford sufficient upgrades. Furthermore, King laments that in many cases developers capture value and spend it elsewhere, not meeting the initially stated public goal.

Michael Kimmelman, architecture critic for the New York Times, thinks we should ask ‘what are the improvements we need?’ before hoping increased density generates them automatically. King, a transportation expert, believes the transit network in East Midtown is already at capacity so we shouldn’t build anything else there. What are the heights that our transit systems and streets can handle? It’s hard to say exactly. But people and firms are adaptable, capacity constraints are elastic. Firms have begun to respond by fragmenting their operations outside of central cores. So it may not be in the city’s best interest to concentrate all transportation investments in Midtown. Furthermore, the solution to our transportation problems is not all capital improvements, King argues; there are service improvements we can and should make too.

Meanwhile, nobody’s talking about what mobility will be 20 to 30 years from now, says Lise Anne Couture, an architect. Mercedes-Benz’s CEO thinks we will have driverless cars in ten years. What about using the waterfront and ferry transportation? What about rethinking the yellow cab? Most passengers are single riders so why does the “NYC cab of the future” need to be a big minivan? Who are the workers? Since the 1980s, the demographics have changed – it is now more desirable to raise a family in the city. We need to stand back and think about what this city will be even 50 or 100 years from now.

After the discussion, an audience member asked, if all of you were on the city council, how would you vote? Dolkart, Couture and Kimmelman each gave a concise no. King and Ascher offered careful, conditional support. Couture wishes the plan was more visionary. Dolkart wishes the plan involved more actual planning. But Ascher, in defense of City Planning, says there exists a genuine sense that the East Side has some problems and they have tools they can use to solve them. “I don’t ascribe any more sinister motives.”

“I don’t think this is an evil plan,” Kimmelman retorts, “I think it’s a half-baked plan.”

Subscribe to our newsletter