After-Hours Tour of the Fraunces Tavern Museum: "Path to Liberty"

Explore a new exhibit inside the oldest building in Manhattan, a witness to history throughout the Revolutionary War Era!

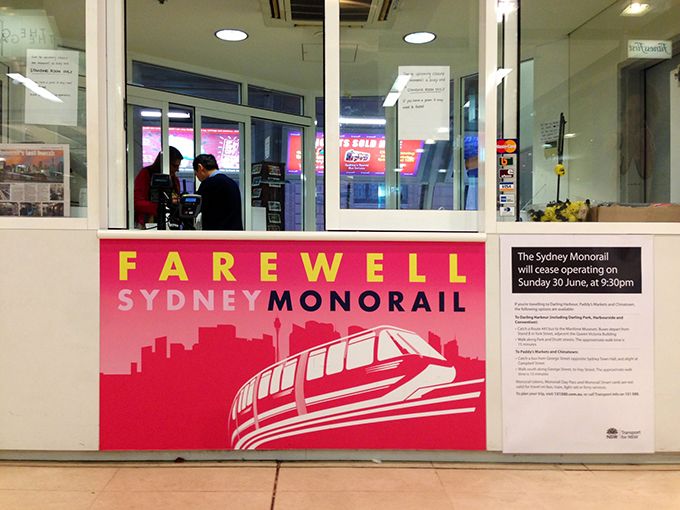

At first glance, the gleaming blue harbour with the view of the Sydney’s Harbour Bridge in the distance does not seem like an appropriate setting for a monorail, a form of public transportation reminiscent of Disneyland. But over time this odd piece of urban infrastructure grows on you, not for what it is or what does but the unique interfaces that it has with Sydney. But on June 30th, the Monorail will cease operation, begging the question: What will become of the infrastructure?

Since it was first proposed in 1984, the monorail has been a contentious piece of transport infrastructure. Its original incarnation was aimed to stitch together redevelopments in Darling Harbour with Chinatown and the Central Business District (CBD). However, after 24 years of operation, it has reached the end of its economically viable life. In March 2012, the New South Wales government purchased Metro Transport Sydney, consequently announcing that the Monorail would be removed. In a contrasting move, Sydney’s light rail line will revert to public ownership with what the state government is calling a “once-in-a-generation” opportunity to fix public transport in the CBD.

The current monorail network sits as a separated loop with no relationship to Sydney’s wider public transport network and therefore has become a glorified and expensive central Sydney tourist shuttle. The monorail was set to carry 12 million passengers a year, however within its first two years, usage numbers were half this prediction. More recent figures show a further 20 percent decline in the last four years, with almost four million users; a large percentage of which were tourists. As usage declined, maintenance costs kept increasing and became harder to justify. Costs were transferred onto the customer and regardless of trip length—one station or the entire loop—the cost of a ticket became a flat rate of $5.

The removal and decommission of Monorail infrastructure is being managed by Transport for NSW. From the steel tracks to the supporting columns, service wires and signage; all infrastructure associated with the Sydney Metro Monorail will be dismantled and removed from mid August 2013 to March 2014. Its removal will make way for the development of the new Sydney International Convention, Exhibition and Entertainment Precinct (SICEEP) in Darling Harbour, another controversial project. One contentious project making room for another. As previously demonstrated by the city’s once-extensive tram system and historical laneways, Sydney has built a reputation for the implementation and erasure of infrastructure. In this case there has been no interest by government bodies to develop this infrastructure into an integrated transport element.

So what happens now?

Before the plans to dismantle the monorail’s structure were announced, a handful of design proposals suggested a possible future for monorail in the city. David Vago’s ‘High-Lane’ (clumsily referring to Diller Scofidio + Renfro’s High Line in New York), sees a transformation of monorail tracks into an elevated boardwalk and cycleway.

However, this project raises many fundamental questions. The proposed path would only be around 3 meters wide for the greater part of its length and therefore form nothing more than just a walkway. Its functional capacity is nowhere near comparable to the High Line, which has gardens, programmable spaces and flexible seating and recreation areas. KI Studio has proposed a series of elevated hanging gardens at different places along the track which apparently suggest the potential of the space underneath to be used for recreation space, cafes and bars. While utopian in their visions, the proposals reflect the criticism originally faced by the monorail, that its route has no relevance to the urban fabric and does not connect integral parts of the city. Could hanging gardens ever have that agency? We will never know.

In a world where public expenditure is becoming more and more difficult to secure, the complete erasure of public infrastructure doesn’t seem like the smartest course of action. While the monorail’s elevated tracks will be removed, the shadow of the monorail will still be visible, revealed in the spaces where stations once stood and in the series of insertions that have been made into buildings, where the monorail once passed. The uniqueness of these spaces should not be overlooked in creating Sydney’s future above the ground.

William Feuerman is a New Yorker (via Los Angeles and San Francisco) who is currently living in Sydney, Australia. He is the principal of Office Feuerman, a Sydney based design office, and is a Senior Lecturer and the Course Director of the Bachelor of Design in Architetcure at the University of Technology Sydney (UTS). You can follow him on twitter @OfficeFeuerman.

Subscribe to our newsletter