100th Anniversary Great Nave Tour at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine

Celebrate the 1925 construction of the stunning nave inside the world's largest Gothic cathedral!

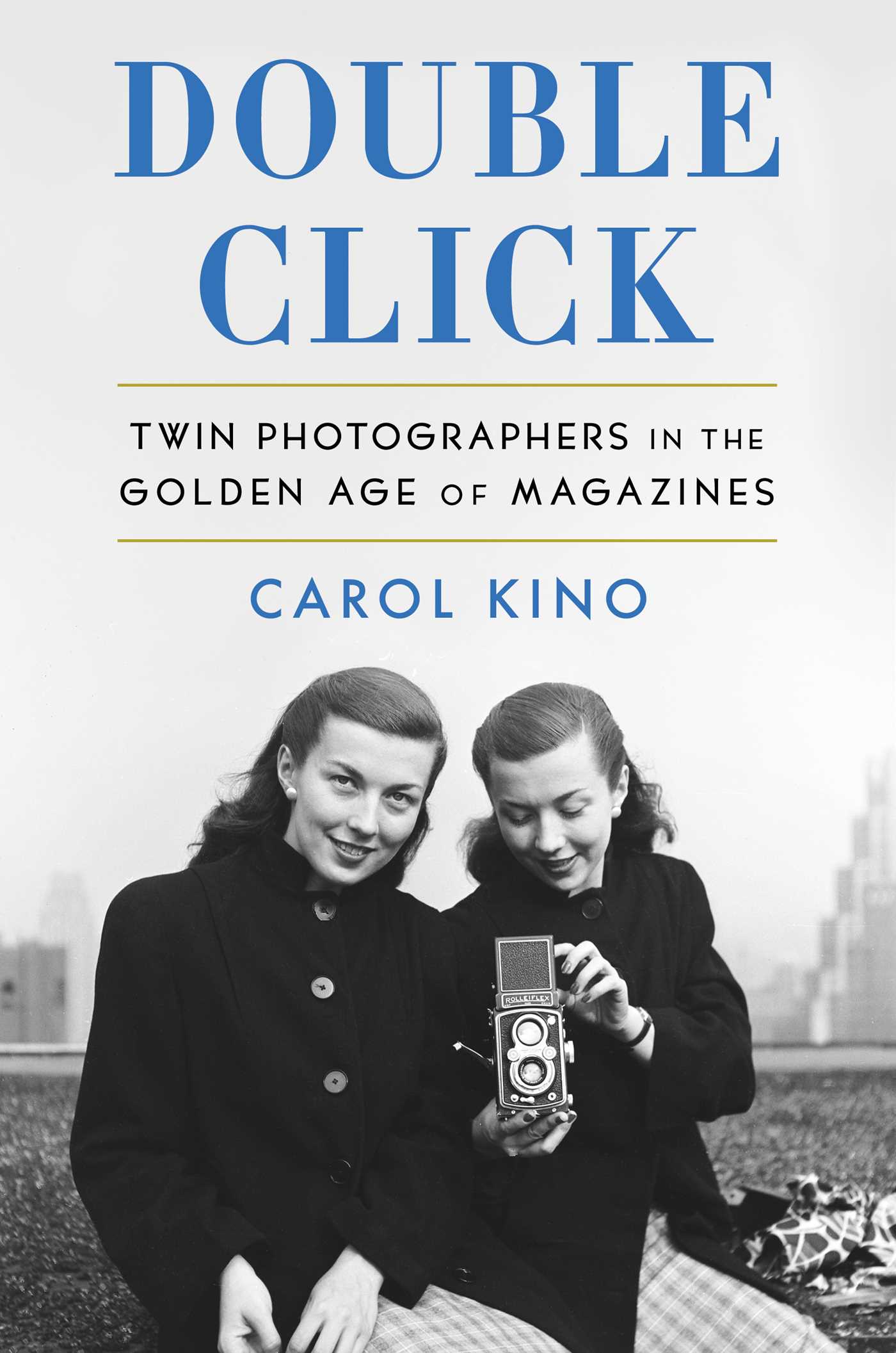

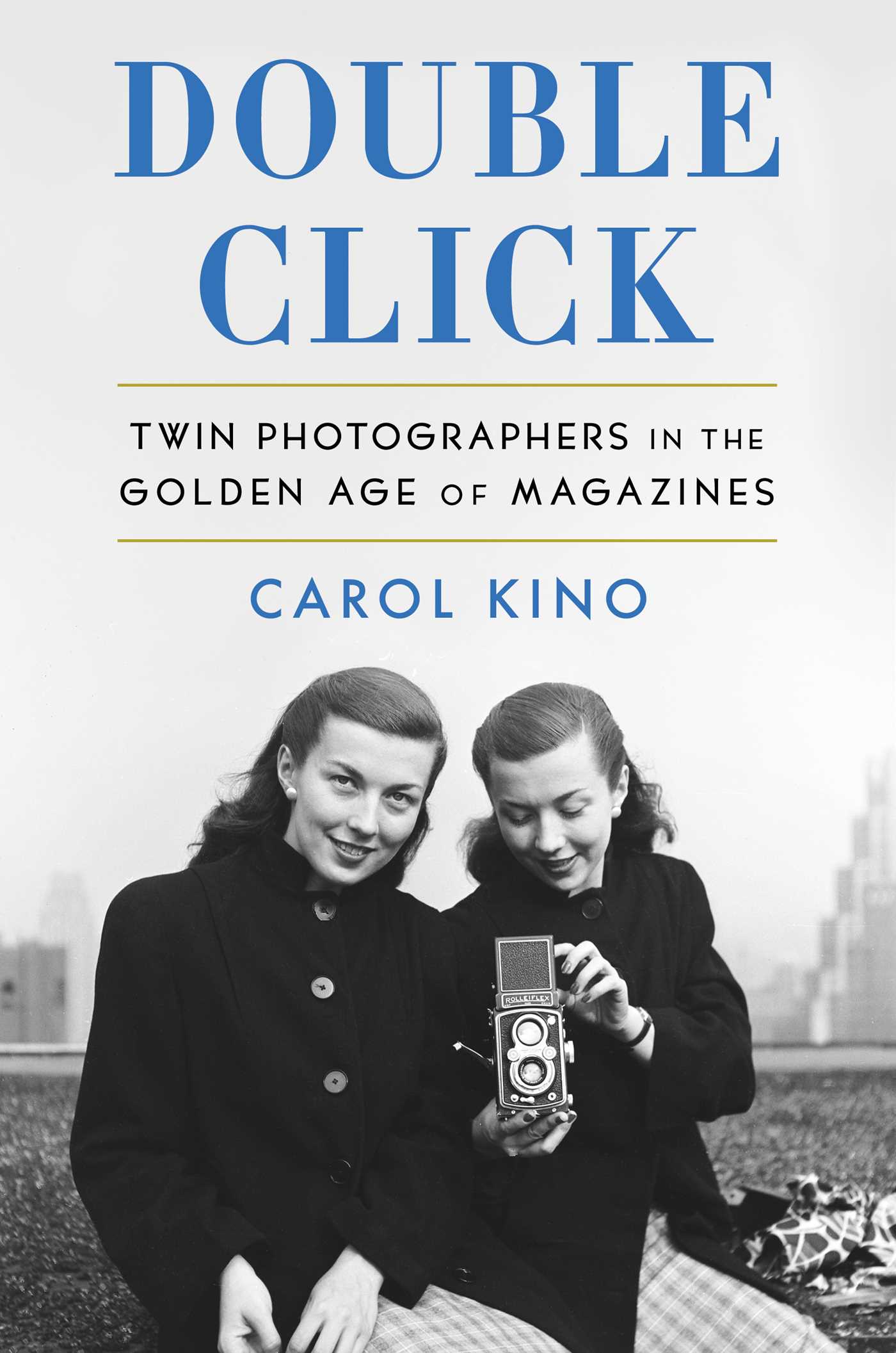

The book Double Click is about the McLaughlin twins, two pioneering female fashion photographers who came of age in Brooklyn.

Carol Kino’s new book Double Click is like a fine wine that reveals itself and opens up the more you go. Ostensibly about two twin female photographers who came of age in Brooklyn and became pioneering fashion photographers in the era around the Second World War (premise enough for me to dive into this book), Double Click is actually about far more. Kino presents a lost world of glamour and opportunity, particularly for plucky young women like the McLaughlin sisters Franny and Fuffy, as they navigate a brave, exciting new world in the magazine industry.

Join us for a candlelit literary salon on March 19 with the author of Double Click, Carol Kino, in conversation with Untapped New York founder Michelle Young:

Lit Salon: Double Click

Can’t join in person? Get a virtual ticket here!

Fatherless at a young age, the twins were shepherded through life by a stylish, persevering mother and photography-fanatic spinster aunt, who gave the twins their first camera—a Voigtländer Brilliant that cost about $730 in today’s dollars. And with that, fate was literally handed to them in the form of a small black box.

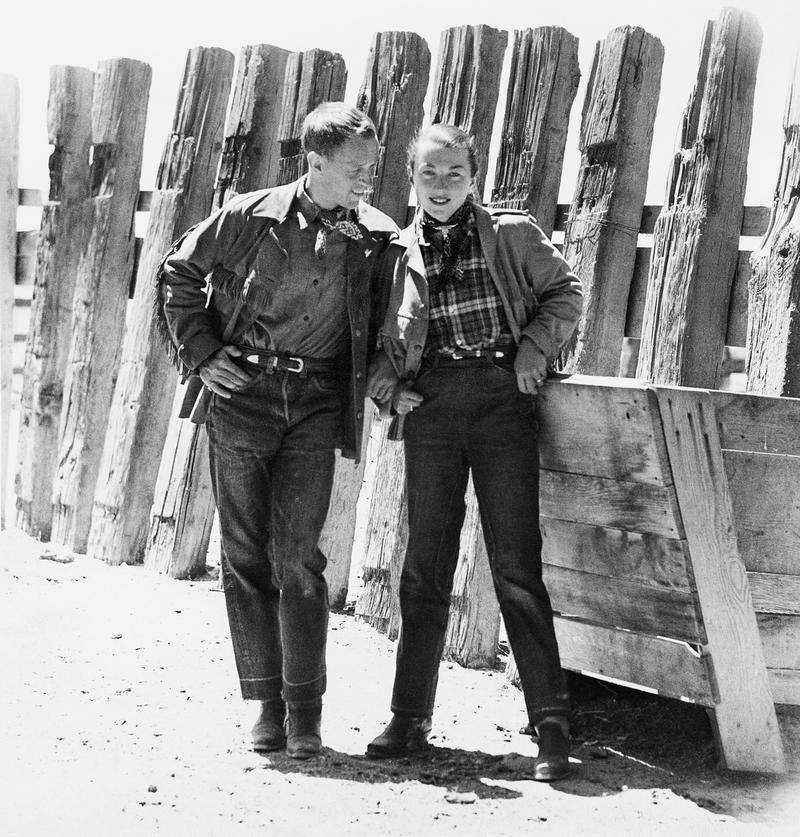

The twins did everything together. They spent their free time during college at Pratt in Brooklyn in the new darkroom and getting their photographs into publications aimed at a new coveted segment of the American market: college-going women. With their beauty and style, they were also getting written about in gossip columns and magazines, and their upbringing in Connecticut in proximity to Choate put them in a rarified social circle. John F. Kennedy was an early beau, of both, of course. As written in Prattler magazine,

“Double dates are their usual rule, but occasionally they’ll go out singly, or both with the same man—who usually recovers.”

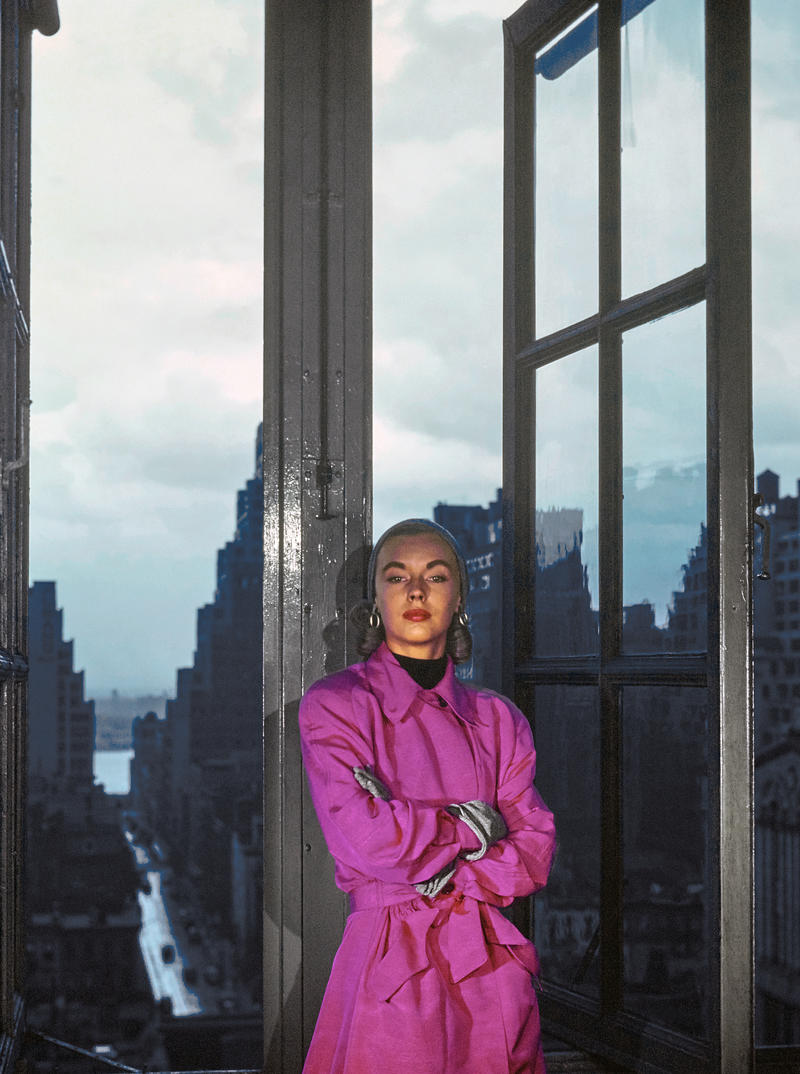

Pratt had an astounding job placement rate due to its focus on training students with actual, applicable trade skills. The twins entered the magazine world with a uniquely American style of photography that emphasized movement and shots in nature, which included the concrete jungle of New York City. The subways, the streets, the sidewalk book stalls, the twins’ apartment: everything around them became their inspiration.

During the war, Franny photographed stories for Glamour on American women factory workers. She also discovered some of the horrors of war in a convalescent home for blind soldiers, although the magazines did not print almost any of her images. Some of twins’ photographic female counterparts, like Lee Miller and Toni Frissell, headed over to Europe to document the ravages overseas. After the war, American photography became a freeing antidote to the formality of French fashion and imagery. In Franny’s own words at the time,

“The new-look American girl is the girl on the move with her feet on the ground. The girl who is going places & knows where she is going.”

Double Click was initially planned as a book about women in photography in the 1940s and ’50s, and it still is, which makes it all the better. The figures whom the twins came in contact with and often worked directly with or for, read like a who’s who of New York society: Cecil Beaton, Edward Steichen, Margaret Bourke-White, Condé Nast himself, Richard Avedon, Irving Penn who dated Franny, Georgia O’Keefe, Alfred Stieglitz, and many more. It is a book that in many ways uses the twins to reveal the forgotten yet immensely talented women in media and photography pre and post-war, and tracks how their role shifted and evolved.

The book also reveals how New York City itself reacted to war, through the lens of its women, bringing to life the energy and enthusiasm with which women took to volunteering and working in fields previously closed to them. And the imperative of the fashion industry cannot be understated—even Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia weighed in. LaGuardia was the brainchild behind a line of fashion-forward uniforms sold in department stores around the country during the war, which also helped to promote numerous young, female designers. Eleanor Roosevelt served as LaGuardia’s deputy in this fashion endeavor. Kino writes:

By the time the tiny, personality-packed cigar-chomping mayor had dreamed up the idea of fashion-conscious uniforms, he had already taken the New York fashion world under his wing as a pet project, perhaps because of his previous life as a lawyer, when he’d worked with the garment industry.

Kino shows us a golden age of publishing when a photographer like Franny, the only female in-house Condé Nast photographer, made $450,000 a year in today’s dollars. Fuffy held her own as well, working for Mademoiselle, Harper’s Bazaar, Junior Bazaar, and Charm, before starting a lucrative business photographing children unposed for magazines. It marks a sharp contrast to the media industry today, in dire financial straits, with rounds of layoffs the new norm. The idea that a magazine could hire artists like Marc Chagall and Jacob Lawrence to do the visuals in an issue seems so foreign to readers today.

Kino also begins to address, although perhaps leaves this subject for another time, the problems in the fashion industry that will explode in later decades: underage models (like Carmen Dell’Orefice who was injected with hormones to speed up her puberty). Just as Kino shows how today’s fashion trends all began so many decades ago in the war and postwar period—ballet flats, leotards, and tights as day wear for example—she also shows how women’s freedoms were strategically eroded post-war by the very magazines that once celebrated the new female. “These Bright Young Men” was the headline of one Junior Bazaar story which showcased five eligible single men including Gore Vidal, Vernon Hughes, and Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr.

Where women were once lauded for their skilled work in the factory, they were now taught how to be good entertainers and good flirts to get a good husband. Wedding coverage and motherhood stories were now core parts of the editorial strategy. A popular book, Modern Woman: The Lost Sex based on a regular column in Glamour by a female psychiatrist Marynia F. Farnham, encouraged women to be content with what they had, avoid premarital sex, and look for a husband. As Glamour wrote, Dr. Farnham showed that “a great part of the world’s ills are profoundly traceable to the fact that modern woman is unconditioned to fulfill her destiny” and that destiny was to raise men who could then shape the world.

Double Click is a reminder that gender relations in America have been cyclical, despite periodic large leaps forward. Women today will identify with the story of the McLaughlin twins, and perhaps be surprised how much they were able to achieve so many decades ago.

Join us for a candlelit literary salon on March 19 with the author of Double Click, Carol Kino, in conversation with Untapped New York founder Michelle Young:

Lit Salon: Double Click

Can’t join in person? Get a virtual ticket here

Subscribe to our newsletter