After-Hours Tour of the Fraunces Tavern Museum: "Path to Liberty"

Explore a new exhibit inside the oldest building in Manhattan, a witness to history throughout the Revolutionary War Era!

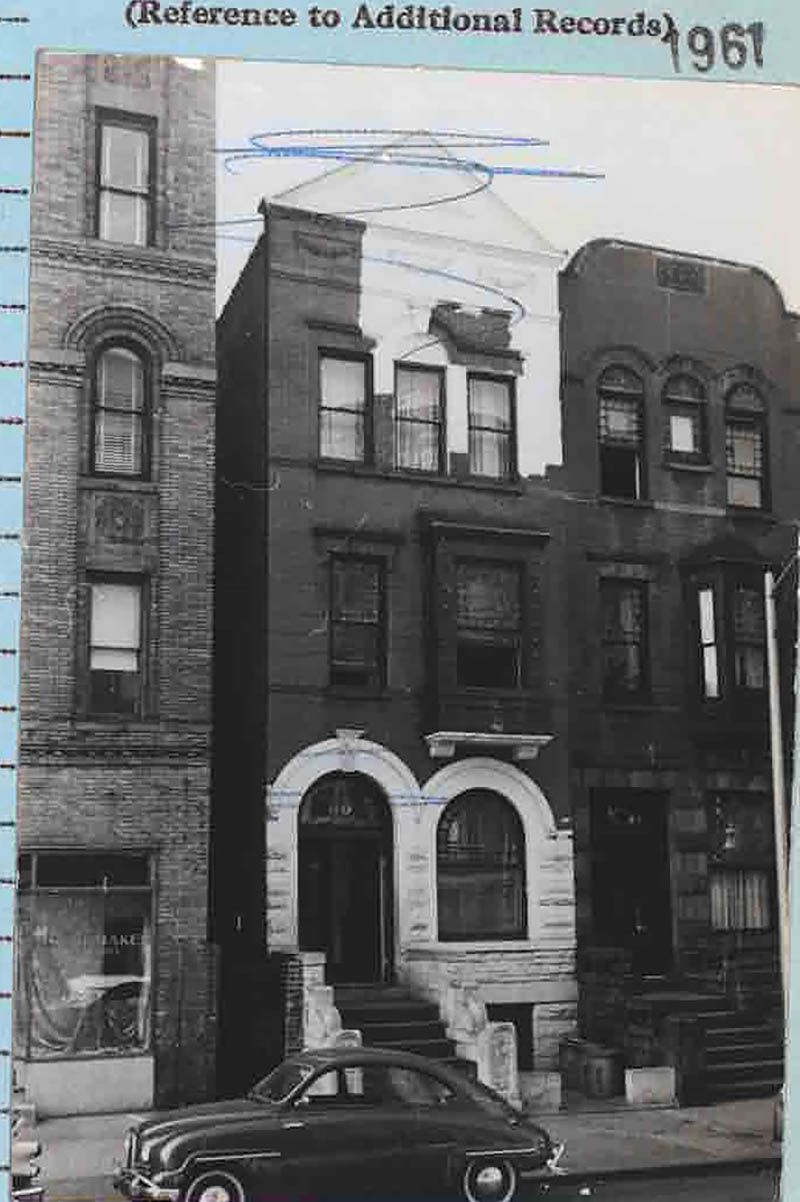

On February 28, 2021, the New York Landmark Preservation Commission approved the design and construction of a five-story family townhouse at 110 West 88th Street in the Central Park West Historical District on Manhattan’s Upper West Side.

Perhaps neither the Landmarks Commission, DXA Studio of architects, nor real estate agent Leslie J. Garfield are aware of the extraordinary historical significance of the only building ever erected on the lot, a four-story brownstone designed by Samuel B. Reed and completed in 1888. In the first week of April 1917, the building became the epicenter of what would subsequently be mythologized into the most important event in 20th-century art.

For it was from this address that a urinal, signed R Mutt, was sent to the Grand Central Palace on Lexington Avenue. It arrived on the 9th, where it was summarily rejected because Mutt was not a member of the exhibiting Society of Independent Artists putting on the show. The 2,150 works were still being hung by Marcel Duchamp but were scheduled to open the next day.

Whilst Mutt didn’t exist at all, his urinal would eventually be attributed to Marcel Duchamp and hailed as a seminal creation in modern art—the first of the “readymades,” or art created from found objects. Until 1932, nobody suspected or accused Duchamp of having been behind the work. Not a soul mentioned it, and no evidence survived to prove it—and he did not claim authorship until the 1960s when the key figures involved had already died.

Moreover, on both April 11 and 14, 1917, Duchamp would disclose to two different individuals that not he but a female friend had been responsible for the urinal. A letter from Duchamp himself to his sister states, “One of my female friends who had adopted the masculine pseudonym Richard Mutt sent in a porcelain urinal as a sculpture.” This is confirmed by the fact that his handwriting appears neither on the attached label nor the urinal itself. But his female friend’s does.

The answer to the question of who had been responsible for Mutt’s urinal’s journey from Philadelphia to the Grand Central Palace via 110 West 88th Street lies in the printing and the handwriting. The first in one hand, the second in another. They were in fact from the hands of two women. The first woman has been marginalized in art history, while the second has remained completely anonymous.

One of the women who may have actually created the artwork was Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. She was a resident at the time in Philadelphia, when according to the two leading critics of modern art in New York—Gustav Kobbé of the Herald and Henry McBride of the Sun—the fictitious hoaxer Mutt had sent the urinal to the exhibition venue via 110 West 88th street. This explains the two different hands: the first done in Philadelphia by Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, and the second in New York by somebody else.

The address on the label, 110 West 88th Street, was the residence of a certain Louise Norton, friend of both Elsa and Duchamp. All three were part the avant-garde milieu that regularly met at the apartment of Walter and Louise Arensberg at 33 West 67th Street, where Duchamp also lived.

In her biography of her second husband, Edgard Varèse, Louise Norton Varèse remarked that in 1917, she employed a housekeeper at 110 West 88th Street named Mrs. Kiernan. The only person of that name working as a housekeeper in Manhattan in 1917 was Jennie Kiernan, as recorded the year before in 1916—the same year that Louise Norton moved into 110 West 88th St. There is only one Jennie Kiernan from 1916 listed in the New York City Directory, then living at 148 West 125th Street. By 1917, Mrs, Kiernan was living in the rear section (r201) of West 142nd Street, with Mr. Henry Kiernan, a steamfitter. A Robert Kiernan, a Post Office carrier, lived in the front half of the building (h201).

According to Norton, in April 1917, one floor of 110 W 88th—owned by her mother—was occupied by Norton herself. She rented the top floor to Juliette Roche and Albert Gleizes from France. Unlike Duchamp, Gleizes was exhibiting in the show. Upon leaving New York for her summer vacation ‘out West’ on May 22nd, Norton rented out her apartment to Francis Picabia, also in the show, and Gabrielle Buffet-Picabia, who had arrived in New York in the first week of April from Barcelona.

At this time, when 75% of domestic servants in New York were of Irish descent, it was quite common for a housekeeper of what was quite a modest family row house not to “live in.” In the Varese biography, Norton records an encounter she enjoyed with her housekeeper on her return to New York in the autumn about Picabia and Varese:

With my apartment the Picabias had taken over Mrs Kiernan my housekeeper, so-called because of her extreme respectability, dignity, and grey hairs, though she did all the work. When I returned in the fall, Mrs Kiernan gave me an outraged account of the behavior of the two young men. “Mrs Norton,” she said, in a dramatically shocked tone, “I am an old woman but I have seen such carryings-on as I never dreamed of.”

If Mrs Kiernan considered herself old in 1917, then she must have been born early in the second half of the 19th century. That being so, she would have learned at school to write in the round hand visible on the label attached to Mutt’s urinal in Stieglitz’s photograph: the script betrays a hand formed some fifty years before 1917. A round hand was not being taught in either commercial or common schools in the late 1890s or early 1900s when Louise Norton was being taught her penmanship.

Life expectancy for women in the U.S. in 1917 was age 54. Since, according to the Census of New York of 1900, Jennie Kiernan had been born in 1852, she was in 1917 of an age that could justifiably be characterized as ‘old” at 65. She would have received her basic instruction in handwriting in the 1860s.

As confirmed by her observation that her housekeeper, Mrs Kiernan, “did all the work,” the comfortably well-off “New Woman” Louise Norton was clearly enjoying a fulfilling social life in the period following her separation from Allen Norton in 1916.

This hectic bohemian lifestyle demanded her almost constant presence in Greenwich Village, so it would seem reasonable to suppose that, imposed on by the routinely demanding Elsa by phone from Philadelphia, Louise might have outsourced a task. She may have informed her maid that, on reception of a crated urinal from Penn Station, Mrs. Kiernan should perform the following task: Firstly, complete, in her highly legible, venerable hand, the official label with the name Richard Mutt, the address of the house and a title for the work since there was none on the urinal itself. Then, attach the label to the urinal and arrange its transport to the Grand Central Palace, post-haste. Even though Louise was not a member of the Society, she could fall back on her and Elsa’s mutual friend, Mina Loy, who had a spare label since she had submitted only one work,

Elsa was not renowned for her social graces. Habitually uncompromising, forceful and even violent in her demands on strangers and friends alike such as William Carlos Williams, she seemed to have been congenitally incapable of accepting “yes” for an answer and not biting every hand that tried to feed her. One can easily imagine that on receiving a phone call from Elsa instructing her in her duties, Louise would have acted expeditiously for fear of Elsa’s probable retribution if she declined. She was quick to agree and move the thing on, assuring Elsa that she would protect her anonymity as securely as would the pseudonym on the urinal and the address on the label, and as would Mrs Kiernan’s handwriting.

Had Elsa been able to procure a label in Philadelphia, then she would have been able to send the urinal directly to the Grand Central Palace. The fact that she didn’t, though, implies that she couldn’t have. She was not a member and thus needed assistance from a friend in New York—one who was also not a member of the Society of Independent Artists, ensuring that her identity would not be revealed to the directors who might otherwise confirm their prejudices and assume her entry was a hoax. They did reject it anyway, but not until after they had judged it, which was how Elsa skewered them: the directors had democratically dispensed with selection by jury, but she gave them no choice but to judge.

It would have taken much less than a day for the urinal to travel to New York, and a matter of hours in congested Manhattan to travel the 46 streets down and four avenues across to the Grand Central Palace on Lexington Avenue. If in the unlikely event that the highly competent and reliable Mrs, Kiernan might have been unsure how to manage this task, she could of course have consulted Robert Kiernan, the Post Office carrier who shared her roof at h201 West 142nd street.

The Manhattan and the Bronx Directory for 1916 lists more than 429 delivery, removals, and drayage companies operating in New York, one of which was Wells Fargo, which in 1917 offered an intercity collect and delivery door-to-door parcel service. But the easiest way to assure swift delivery to the Grand Central Palace would be to take a taxi, since the urinal weighed 28 pounds.

The most striking feature of the handwriting on the urinal’s label is the exaggerated forward slant of characters typical of common round hand, most pronounced in the almost sinuous ascenders and descenders of the capital “M.” Through diligent research, an almost identical example of a majuscule M has been found on a marriage certificate issued in Rathburn, Ireland, in 1862. In the signature of the Registrar was Samuel Manning who, according to Thom’s Irish Almanac and Official Directory of the United Kingdom of Britain and Ireland of 1878. was the Clerk and Returning Officer of Union in Celbridge, Kildare County, a Kiernan stronghold. This hint of a calligraphic genealogy suggests that the future Mrs. Kiernan might have learned some of her letters from her immigrant Irish parents or grandparents.

And Mrs, Kiernan’s origins would appear to account for the choice of the title “Fountain,” To a respectable housekeeper of Irish descent, what arrived without a label at 110 West 88th Street was quite unmentionable in polite society and inarguably a fualän—a urinal. What left that same address in the same crate, attached to a label completed in Mrs Kiernan’s round hand, was, a fuarán—a fountain, because it said so on the label. Ironically, fualän also means low fellow or blockhead, a synonym in 1917 for “mutt.”

Elsa had good reason to send Marcel a urinal, since in January 1917 he had appeared as a witness for the plaintiff in a divorce trial in which Elsa had been named as co-respondent. In French slang, to send a urinal to somebody is “envoyer un pisser à quelqu’un” which, if stated in rage from the gutters from which Elsa sourced her art materials, defaults into “envoyer pisser quelqu’un,” meaning to reprimand someone, to tear them off a strip–to piss all over them. She referred to Duchamp in one of her poems as “Marcel Dushit.” The inaugural exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists provided Elsa with the perfect opportunity for revenge, since Marcel was the director of the society put in charge of the hanging.

Duchamp did not begin to take credit for the urinal until 1950, 23 years after Elsa died. Perhaps it was an act of revenge, appropriating not only Elsa’s urinal but also her discourse—a challenge to the Independents to show a urinal as a work of art. By that time, Alfred Stieglitz, who had photographed the original “Fountain” in his studio following the exhibition, had also died. As Siri Hustvedt writes in The Guardian, “Duchamp said he had purchased the urinal from JL Mott Ironworks Company, adapting Mutt from Mott, but the company did not manufacture the model in the photograph, so his story cannot be true.”

Yet, Hustvedt continues the art history world has refused to acknowledge an alternative origin for the famous urinal: “The museums, including the Tate, have not budged. The standard Fountain narrative with Duchamp as hero goes on. I am convinced that if the urinal had been attributed to the baroness from the beginning, it would never have soared into the stratosphere as a work of consummate genius. Women are rarely granted such status, but the present reputation of Fountain, one that was hardly instantaneous but grew slowly over the course of many decades, has made the truth embarrassing, not to speak of the money involved and the urgent need to rewrite history. The evidence is there. They can’t or won’t see it. Why?”

110 West 88th Street was demolished in about 1965, which we confirmed through contacting the NYC Municipal Archives. Ken Cobbs, Assistant Commissioner from the NYC Department of Records shared with us the tax assessment record for the years 1965-66 which notes a “demo” (demolition) took place. The lot at 110 West 88th Street has been empty since then. If you’re also curious as to what the Grand Central Palace was where the exhibition was held in 1917, it was built as part of Terminal City, a development around Grand Central Terminal. Grand Central Palace was demolished in 1964 and became 264 Park Avenue.

Next, check out Eight Homes of Famous Writers and Artists in NYC, Including Marcel Duchamp!

Subscribe to our newsletter