Fiber Arts Take Over a Former Seaport Warehouse in NYC

See waterfalls of fabric, intricate threadwork, massive tapestries, and more!

Long before the world at large recognized the brilliance of African art, the Brooklyn Museum—that McKim, Mead and White masterpiece dominating Prospect Park’s northeast corner—presented African sculpture, fabric, and jewelry as art rather than ethnographic material, noted Holland Cotter in the New York Times. In 1923 it produced the largest exhibition of African art ever held anywhere, one that was superior in every way to the Museum of Modern Art’s more celebrated show of 1935. The museum’s permanent African collection is extraordinary, as is the ongoing African Innovations, which builds on the Akan proverb, “One must turn to the past to move forward.”

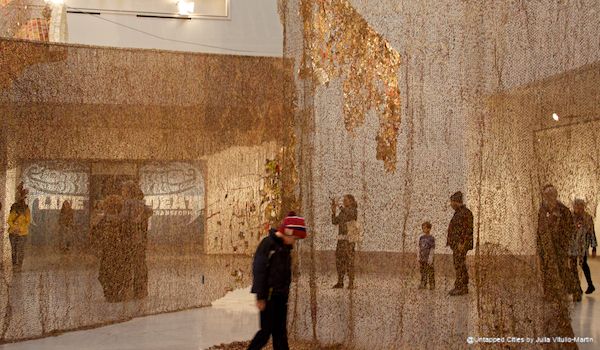

Now the museum has mounted an exhibition—Gravity and Grace: Monumental Works by El Anatsui—that is so spectacular on its own terms that people nonchalantly emerging from the elevator gasp in wonder when they first encounter the huge draped sculptures. Born in Ghana but living in Nigeria since 1975, El Anatsui is the “first and only black African artist to achieve global recognition at the highest levels while living and working continuously in Africa,” says Susan Vogel, author of the definitive El Anatsui: Art & Life.

In describing Gravity and Grace (2010) for Vogue Magazine, Leslie Camhi called it a “giant shimmering tapestry in colors of pale pewter and lustrous gold.” Constructed from thousands of crushed, twisted, and joined liquor bottle caps, Gravity and Grace is “both entrancingly beautiful and historically complex, transforming the refuse of an impoverished continent into something uniquely luxurious.” You might object to some of this language but Camhi is making a legitimate point about El Anatsui’s gorgeous, almost sumptuous works of art—such as Gli above or Drifting Continents below—in which gold, hoarded as the world’s most precious metal for much of human history, seems to dominate. But the tapestries aren’t made of gold—they’re made of bottle caps, aluminum, and copper wire, commodities as valueless as anyone could imagine. This forces the viewer to think about our idea of inherent value. The tapestries look rich enough to provoke war, or to be made into ceremonial robes for a Versailles king or an African chief. Yet their value is entirely in the art, not in the materials.

Surely El Anatsui’s ongoing display of gold as a falsely valuable commodity is no accident. When he was growing up in Ghana his country was a British colony called the Gold Coast, a remnant of centuries of brutal exploitation of African riches by Western nations. Further, the screw-top liquor bottle caps used in Drifting Continents and many other pieces highlights his point that the historical international trade, including the slave trade, linking Africa, Europe, and the Americas had alcohol as an important element. He calls the bottle caps as well as the tin milk cans he uses in Peak “commercial flotsam,” asserting Africans’ participation—for better or worse—in the global consumer trade.

El Anatsui’s art stops people in their tracks, says Dumouchelle, the Brooklyn Museum curator. “People look at it closely and think about it,” he says. “There’s a deep symbolic, metaphorical language beneath the visually stunning surface. His work challenges our expectations of what sculpture can do.” This is true of El Anatsui’s work in the Brooklyn Museum, but may be even more profoundly true of Broken Bridge II on the High Line. Every city lover will want to see it, for it captures and reflects back at us both Anatsui’s urban vision and the reality of New York City itself. Anatsui told Art21, “I come from a place where you have a lot of sky. The sky starts from almost ground level and goes up. But over here you have to really look up to realize that there is eventually sky somewhere. That’s almost the experience of most people who live in open country and they come to New York—sky is not a common commodity.” New York’s sky is both vivid and beautiful, as Broken Bridge II shows, and New Yorkers treasure it as the scarce, inherently valuable commodity that it is.

GETTING THERE: The Brooklyn Museum is located at 200 Eastern Parkway, accessible by the IRT 2/3. When you emerge from the Eastern Parkway/Brooklyn Museum stop you’ll be at the museum’s front steps.

Hours: 11:00 am-6:00 pm, Wed; 11:00 am-10:00 pm, Thurs;11:00 am-6:00 pm, Fri-Sun.

The Brooklyn Museum’s Target First Saturdays offer visitors free programs of art and entertainment from 5 to 7 pm. This month’s First Saturday on March 2 will be devoted to El Anatsui and will include music, films, and a curator’s talk by Kevin Dumouchelle.

Subscribe to our newsletter