Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

The United Nations was created to replace war and bloodshed with dialogue and compromise. But the five avenues west of the UN’s East River location have been home to over 350 years of war history. From decapitations to anti-war rioting, these five avenues are a reminder of the violence that the UN was established to prevent.

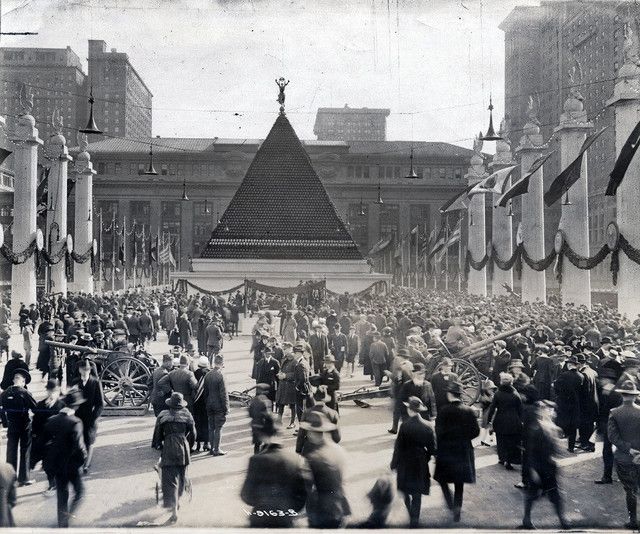

A pyramid of 85,000 German army helmets from WWI. Photo via Smithsonian Institution.

Five avenues west of the United Nations is Park Avenue, today the home of Grand Central Terminal and a slew of corporate headquarters. In 1919, it was the home of two enormous pyramids made of German army helmets. 85,000 German army helmets, to be exact. After the Allies won the First World War, American soldiers captured the helmets in a supply depot in Europe and brought them back to the States. Then the American government displayed them outside Grand Central Terminal to convince New Yorkers flush with pride to buy war bonds. German helmets were also awarded as prizes to government workers who successfully sold the bonds.

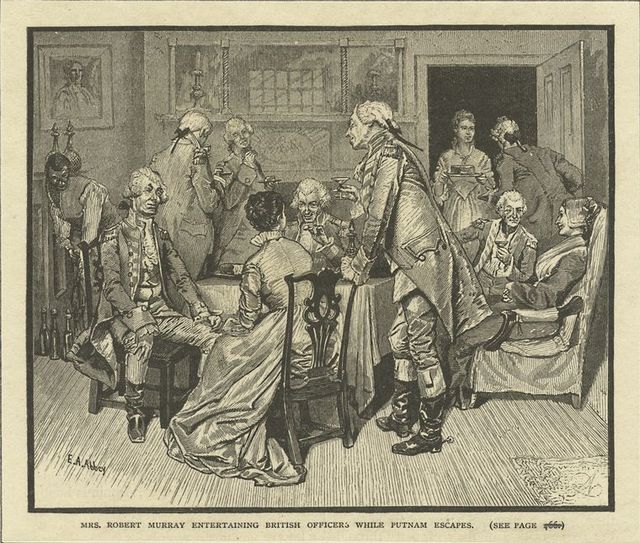

Photo via NYPL Collections

One avenue east of Park is Lexington, where legend has it wealthy New Yorker Mary Murray helped George Washington escape British domination in 1776. Washington had just had his hat handed to him in the Revolution’s first major battle in Brooklyn, known as the Battle of Brooklyn or the Battle of Long Island. The continental army barely made it out of Brooklyn alive, and was hurrying to leave Manhattan in September of 1776. Historians have written that Mary Murray (of Murray Hill fame) decided to invite key British officers over for tea at her Lexington Avenue estate just as Washington retreated, buying him valuable time to escape.

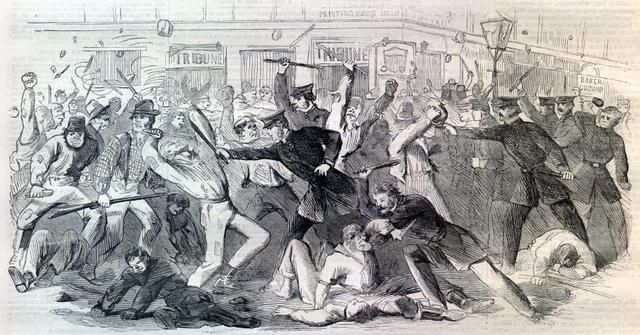

Image via Harper’s Weekly via Wikimedia Commons

On 3rd Avenue and 46th street, just an 8-minute walk from the United Nations, New Yorkers started one of the bloodiest urban riots in American history. The year was 1863, and the Civil War was in full swing, much to the chagrin of prominent New Yorkers. Mayor Fernando Wood, for one, publicly called for the city to secede from America and form a trade partnership with the southern states, and many working class residents strongly opposed ending slavery. So when the government tried to draft New Yorkers, all hell broke loose. On July 13, 1863, 500 New Yorkers converged on the draft office at 3rd Avenue and burned it to ground. Thus began a 3-day citywide rampage, the Draft Office Riots, that left over 100 dead, including 11 African-Americans that rioters lynched in the streets.

Check out 8 urban battlefields from the Draft Office Riots.

Image via NYPL

Image via NYPL

In 1641, the Wickquasgeck trail, which became modern-day Broadway, connected Native American villages to the Dutch settlement at the southern tip of Manhattan. Colonist Claes Swits ran an inn along the trail, at today’s 2nd Avenue and 47th Street. One night in 1641, a Native American man came to the inn with an axe and decapitated Claes Swits. He did so in retaliation for an earlier settler attack that had wiped out his entire family. New Amsterdam’s Director General Willem Kieft demanded that the man be captured and punished, but Native Americans leaders shielded him. Kieft then used the decapitation as a pretext to slaughter the Native population.

In 1965, devout Catholic and pacifist Roger Allan Laporte sat outside the Dag Hammarskjold Library at the United Nations building and burned himself alive to protest the United States’ involvement in Vietnam. LaPorte’s suicide was the third such anti-war immolation that took place in America in 1965. Before he died, the 22-year-old told reporters, “I’m a Catholic Worker. I’m against war, all wars. I did this as a religious action.”

Next, check out the Top 10 Secrets of the United Nations or the Secrets of Grand Central Terminal

The author, Avram Billig, is the creator of the website and mobile app Pastport, which explores New York City’s fascinating history. Avram is also a researcher and writer with work published in The Atlantic and The Huffington Post.

Subscribe to our newsletter