Fiber Arts Take Over a Former Seaport Warehouse in NYC

See waterfalls of fabric, intricate threadwork, massive tapestries, and more!

Before New York City became a modern cityscape, much of the land was farmland. But early in New York’s history, slavery was practiced throughout what would become the five boroughs, as well as on Long Island and in the upstate regions. Slavery was introduced to the city as early as 1626, just shortly after the first Dutch settlers arrived. When the English took over the city in 1664, the Black population was approximately 9%. This would only grow as slavery became significantly more widespread, with about 40% of white households owning slaves. Minor slave uprisings were prevalent, including a particularly large one in 1741, and around 7,000 slaves were legally admitted between 1700 and 1774. However, there were free Black communities in and around New York City too.

By 1799, children of slaves were declared free, and it was not until 1827 that New York State Governor Tompkins abolished slavery. Following abolition (and in some cases, prior to abolition), many free African Americans established small communities, many of which were fully economically self-sufficient. While some like, Seneca Village, are known to many New York history buffs, others still remain unknown to most. Here is our guide to 12 free Black settlements in and around New York City, with a bonus one in the Adirondacks.

Seneca Village was settled in 1825 and flourished through 1857, consisting predominantly of African Americans, many of whom owned property. By 1855, the community included 52 homes, a school, and three churches for its approximately 225 residents. Tanner’s Spring was likely a water source for the community, named for Dr. Henry S. Tanner, who fasted for 40 days and only drank water from Central Park’s springs. African Americans began buying property between 82nd and 83rd Streets and Seventh and Eighth Avenues in the mid-1820s, accelerated by the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, which acquired land for a burial ground. Most of the homes were two stories, and most residents were employed as chefs, sailors, coopers, and preachers. St. Michael’s Church established a Sunday School in Seneca Village in 1833, serving as an important community center.

Along with African American residents, there were also Irish and German immigrants living there. Unlike the shantytowns of what would become southern Central Park, Seneca Village was a safe and stable community; owning a home in mid-19th century New York gave many African American residents the right to vote, as well as a refuge from racism, which plagued other parts of the city. However, in 1853, the City of New York acquired the land by eminent domain. Residents were compensated for their land, though many argued that it was insufficient. Construction of Central Park began just a year after the community dissolved in 1858, and by the 1860s, essentially none of the property remained. Residents relocated to other sections of the city.

Though Central Park’s construction erased much of the history of Seneca Village, scholars and archeologists have worked to learn more about this historic community, one of the most famous free Black communities in New York. Historians Roy Rosenzweig and Elizabeth Blackmar were the first to study Seneca Village in detail in the early 1990s, after which the New-York Historical Society organized an exhibit curated by Grady Turner and Cynthia Copeland titled Before Central Park: The Life and Death of Seneca Village. In 2011, the Institute for the Exploration of Seneca Village History conducted an archaeological excavation at the site, which uncovered stone foundation walls and thousands of artifacts from residents, including an iron tea kettle, a roasting pan, and a stoneware beer bottle. However, the foundation bricks, which are commonly considered a foundation of Seneca Village, are actually the remains of a 1930s sandbox.

Weeksville was one of the largest free Black communities in the U.S. prior to the Civil War, located near present-day Crown Heights in Brooklyn. The Weeksville Heritage Center has worked to preserve the settlement’s history and teach the city about its significance. Free Black professionals first purchased land in the area shortly after the abolition of slavery in New York, growing into the second-largest Antebellum-era free Black community nationwide; over 520 residents called Weeksville home by 1855, more than double Seneca Village.

Henry C. Thompson, a leading Black community leader, purchased 32 lots from grocer Edward Copeland (who purchased the land from John Lefferts, whose family names Prospect Lefferts Gardens in Flatbush). Weeksville was officially founded in 1838 when an African American longshoreman named James Weeks bought two plots of land and built a home near what is now Schenectady Avenue and Dean Street. Weeks founded the community with others, including Sylvanus Smith near Bedford Hills, a rather secluded area that would allow Weeksville to flourish as well as be safe from racial prejudice. Quickly, the community grew, and sites such as Zion Home for the Aged, Howard Colored Orphan Asylum, and Bethel A.M.E. Church opened in Weeksville. About one-third of the men over 21 owned land, and the community included many outspoken abolitionists and equal rights activists. The community had one of the nation’s first African American newspapers, The Freedman’s Torchlight, and included Colored School No. 2, which after the Civil War would become the first integrated school in the country.

Weeksville became the national headquarters of the African Civilization Society, which worked to establish a free Black community in Liberia. Residents included Junius C. Morel, an accomplished journalist who collaborated with Frederick Douglass and other leading Black authors of the time. Susan Smith McKinney Steward was the first Black female doctor in New York, while Sarah Smith Tompkins Garnet was Brooklyn’s first female school principal who founded the Equal Suffrage League of Brooklyn. Some residents even moved to Liberia, though most practiced activism in their home community, about 40% of which was southern-born. It was a safe haven for Black New Yorkers during the 1863 draft riots as well. The community declined in the 1880s with the development of neighboring communities and the construction of the Eastern Parkway.

Today, a row of historic homes known as the Hunterfly Road Houses are the only four structures that fully remain from the community, as discovered in 1968 by James Hurley and Joseph Hays. Weeksville Heritage Center was opened in 2005, expanding in 2014 with a modern building. The Weeksville Heritage Center holds exhibitions, events, performances, and a Resource Center dedicated to the “histories of post-emancipation, freedom, and its promise” and historic understanding of 19th century and 20th century African American, Caribbean, and African history. In a quote in the Landmarks Preservation Commission designation report, Lorren McMillen, an authority on the 19th-century wooden architecture of New York City, stated that the Hunterfly Road Houses “are the last buildings in Brooklyn and in the rest of the city with the exception of Staten Island which as a group face on an old original undeveloped highway and retain all the charm of their rustic setting.”

Sandy Ground was a community in Rossville, Staten Island founded by free African Americans around 1828. It was one of the largest free Black communities in New York City, founded after an African American man named Captain John Jackson purchased land in the area. Jackson captained a ship that traveled from Rossville to Manhattan, the only direct mode of transportation at that time. The land quickly became a center of oyster trading, and many residents would harvest and sell oysters at nearby Prince’s Bay. Harsher laws in the South led many residents involved in the oyster industry to move here from the Chesapeake Bay region of Maryland.

Sandy Ground was not as large as Weeksville, but it contained over 50 homes, including the Reverend Isaac Coleman and Rebecca Gray Coleman House. The Baymen’s Cottages, another landmark, were built between 1887 and 1898 for oyster workers at the height of Sandy Ground. It was also an important stop on the Underground Railroad. Rossville AME Zion Church was perhaps the most significant structure within the community, erected in 1854 and led by notable abolitionist Reverend Thomas James. A newer church was built in 1897 and remains today with much of its original form. However, the decline of the oyster trading industry due to overfishing and pollution led to the area’s partial decline, paired with two major mid-20th century fires.

The settlement is also currently considered one of the oldest continuously settled free Black communities in the U.S. A church, a cemetery, and three homes from the settlement are today designated as New York City landmarks, Today, the Sandy Ground Historical Museum is home to the largest collection of documents detailing Staten Island’s African American culture, history, and freedom.

Newtown, Queens, is often considered New York’s first free Black community, located in present-day Elmhurst. Newtown was originally a one-block town surrounded by farmland, and in 1828, the community developed a church and parsonage. It would later become St. Mark African Methodist Episcopal Church, becoming a community center. Pastor and abolitionist James Pennington, who escaped slavery in Maryland, becoming the first African American to study at Yale (though not formally admitted), was a prominent leader of Newtown. Other residents of Newtown are recorded helping fugitives reach the North safely. At an 1862 meeting, residents denounced President Abraham Lincoln’s proposal for resettling freed slaves in other countries. Compared to Seneca Village or Weeksville, though, little was known about the community, at least until 2011.

A little over a decade ago, construction on a lot near the church uncovered the remains of a 26-year-old African American woman who was preserved in an iron coffin. Scott Warnasch, who was the forensic anthropologist/archaeologist for the New York City Office of Chief Medical Examiner from 2005 to 2015, worked with members of the local community in New York to provide both a backstory to the woman’s life and a physical and sociological picture of who she was. Development, though, continues to threaten the burial ground, which might house the remains of about 300 former Newtown residents.

The Green, also referred to as the Douglaston Community, was one of New York City’s oldest free Black communities, located in what is now Jamaica, Queens. The Green began sometime around 1830, though there is little information about the community’s shift from primarily Caucasian to racially diverse. the Green, which had a population of at least 100, was located most likely around Douglass St. and what is now Liberty Ave., between 168th Street and 175th Street. Census data suggests that the Green transitioned from white-owned properties rented out to Black residents to Black-owned homes. The Green had a handful of shops and appeared to have a rather separate economy from the rest of Jamaica.

Though those who lived in the Green developed a sustainable and close-knit community, as many faced regular hostility from the area’s white residents. One of the most prominent voices advocating for abolition was Rufus King, a New York Senator who lived at and names the King Manor Museum in Jamaica. Churches became centers for the African American population to feel welcome and supported, and just a few towns over, Newtown was a similar community of freed African Americans. Much of the Black population in Jamaica banded together since the threat of discrimination and slavery was still very real, even though slavery was abolished two decades prior. Most of the property on the grounds of the Green has been industrialized, although there is one lot that may have the remains of a structural foundation of a building from the era.

Wilson Rantus purchased a plot of land on “the Green” for $120, suggesting he was a person of interest in the community. Rantus signed a petition of Long Island African Americans to receive voting rights and helped to organize a conference in Jamaica “for cooperating with our disenfranchised brethren throughout the State, in petitioning for the right of suffrage.” In 1822, the Presbyterian Church in Jamaica set up a free school, and in the 1840s the church offered a more select academy for students of both races, but Rantus unsuccessfully fought to get a new Black school for Jamaica. Rantus, who at one point owned six properties in the Green, financially backed a monthly magazine by Thomas Hamilton, a pioneering Black journalist who founded and contributed to papers such as The Colored American and The Anglo-African Magazine.

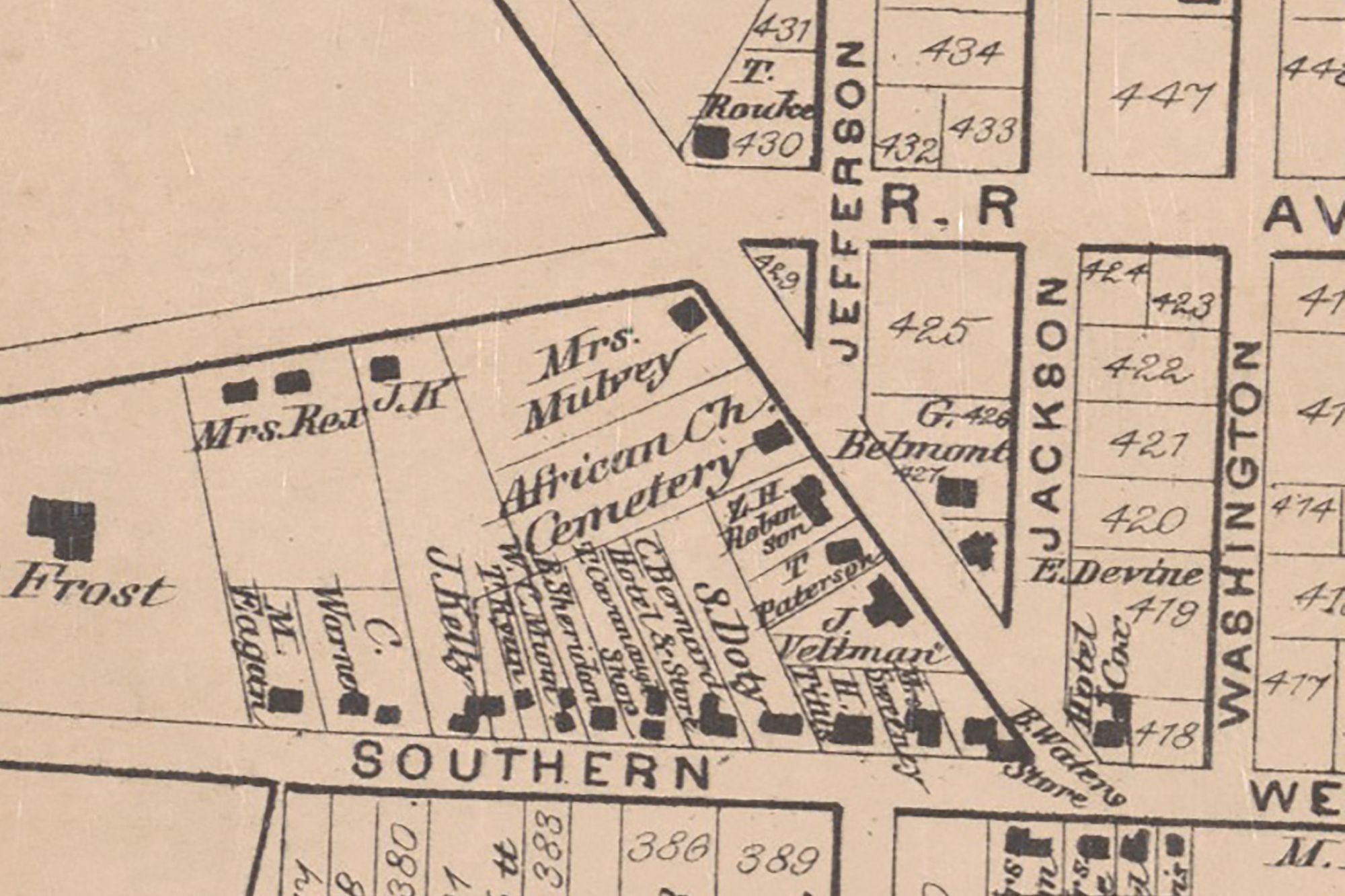

It is believed that there was a small free Black community in the Bronx, located along Unionport Road. The community likely developed around Centerville AME Church, which was founded in 1849 and was the first church to accept Black clergy. A map from the time points out a burial ground by the church for the community’s residents, as well as craftsmen workshops and employers of laborers. The burial ground was perhaps the only independent one known to have existed in the Bronx. The Hunts Point Slave Burial Ground, which was brought to light after the discovery of a 1910 photograph depicting gravestones, is located right by the East River, while this burial ground was located further northeast.

At the time, the community was located in the Town of Westchester, which later became part of the East Bronx. 187 African Americans lived in the town according to the 1840 census. It is estimated that at least 58 individuals were interred in the Bethel AME Church (which would become Centerville) cemetery between 1850 and 1894.

Between 1810 and 1834, years before other Free Black settlements began, a sizeable African American community was established in lower Manhattan around the notorious Five Points neighborhood. Though the nearby African Burial Ground received much attention in the 1990s when it was unearthed, the Five Points community still remains relatively unknown. In Five Points, the African Mutual Relief Society offered aid and occasional housing to African Americans, and nearby churches were community centers for the population. These included the A.M.E. Zion Church, located near slaughterhouses and potteries where free Black laborers worked.

The community got its water supply from the Fresh Water Pond. Some residents of the community also lived in white-owned homes through domestic arrangements. Many African American residents also participated in elections and were taxed, and a handful worked as skilled tradesmen or business owners. On what was then called Block 160, about 30% of residents were African American, many of whom rented homes from white landlords. A number of African American churches were opened in the 1810s and 1820s to cater to the area’s growing population. Many laborer positions in lower Manhattan were occupied by free Blacks, which led to conflict with immigrant Irish populations, Anti-abolitionist sentiment was fierce, and a series of 1834 riots destroyed much of Five Points. Rising rents and a competitive job market led to the decline in the Black population around Five Points.

Skunk Hollow was one of the free Black communities on the New York/New Jersey state line located about a mile south of the Palisades. New Jersey officially abolished slavery in 1846, but free Black residents inhabited Skunk Hollow for decades prior, starting with Jack Earnest in 1806. The community was relatively isolated due to its undesirable terrain for farming. Though residents were not financially well-off, they were still wealthier than other African American families in the region, most of whom owned homes. The Olivers and the Whiteheads, two leading families in Skunk Hollow, established burial grounds on their property.

William Thompson, a minister and community leader, was likely the richest man in Skunk Hollow in the 1860s. Thompson led the Old Swamp Church, which would later become the St. Charles A.M.E. Zion Church after relocating. 75 people lived in Skunk Hollow around 1880, though the community would shortly after decline and be abandoned by the early 1900s, perhaps due to Thompson’s death. However, some families nearby lived in their homes until the Great Depression.

Nassau County was the site of a number of free Black communities, though records for most of them are sparse. After emancipation, many newly freed Blacks established communities across Long Island, including in modern-day Roslyn Heights, Glen Cove, and New Cassel. Roslyn’s African American history is quite well-documented, and it is believed that many free Blacks from the South moved to Roslyn to work on farms, take up skilled labor, and establish churches and community organizations. Some African Americans worked in the shipping and whaling industries as sailors.

One of the most successful free Black communities was established in Spinney Hill located near Lakeville African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church in Manhasset, founded by free Blacks in the 1820s. Spinney Hill is located just a few miles from Lake Success, where a little-known free Black community called Success was located, using the lake as a water source. It is named for Joseph Spinney, a wealthy merchant who built a church on two acres of land he purchased in 1872. Movement to the area picked up in the early 1900s, nearly a century after the church was founded, and many descendants of the original community worked at homes on the Gold Coast of the North Shore.

Sag Harbor Hills, Azurest, and Ninevah Beach Subdivisions Historic District (SANS) is a historic African American beachfront community in Sag Harbor founded following World War II. Some of the residents of SANS are descendants of free Black communities in East Hampton and Sag Harbor. From the early 1800s, the section of Sag Harbor known as Eastville was a community for free Blacks, many of whom attended St. David AME Zion Church built in 1839. Reverend J.P. Thompson was a friend of Frederick Douglass, and it is believed that the church was a stop along the Underground Railroad. Many Sag Harbor whalers are buried in an adjacent cemetery. The community consisted also of Native Americans and European immigrants, many of whom worked in nearby factories. Wives were often property owners so they could preserve their home and family in case a ship didn’t make it back.

SANS became a popular destination for African American families in the 1940s, starting with Azurest. Some built summer cottages on large lots, including major civil rights leaders. Maude Terry and her sister and architect Amaza Lee Meredith came up with the idea for a private community for Black families. The area attracted the likes of Lena Horne and Harry Belafonte, and eventually over 300 Black families bought homes in Azurest and the surrounding municipalities. SANS is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and many historic homes have been preserved for the last few decades.

The Hills was one of the free Black communities in Westchester County, the home of the largest concentration of African Americans in the county through 1870. The Hills was located in modern-day Harrison, North Castle, and White Plains. Many settlers were emancipated by religious groups such as the Quakers and the African Methodist Episcopal Zionists, and the community developed a church, school, and cemetery. The first documents date the Hills back to 1790, and many letters and census data survive (since much of the population was literate).

Stoney Hill Cemetery is all that remains of the Hills today. The cemetery was part of a Quaker land grant to enslaved people who were voluntarily freed, and approximately 200 residents were buried there. As many as 36 residents are recorded fighting in the Civil War, 13 of whom are buried in the cemetery. The burial sites are marked with stone. markers and more recently, with American flags. The cemetery is one of the most significant Black history sites in Westchester, alongside the African American Cemetery in Rye. The Hills survived until around 1925, significantly longer than many New York City communities. Additionally, some free Blacks lived at other Westchester locations such as the Jay Estate in Rye, the home of Founding Father John Jay.

Guinea Town was located in modern-day Hyde Park in the Hudson Valley. It was established in the 1790s and survived until 1850, built by free Blacks. Guinea Town was particularly significant as a key location along the Underground Railroad to Nova Scotia. At its peak, Guinea Town had over 60 families, and it was led by Eliakim Levi. He was a conductor on the Underground Railroad alongside followers of abolitionist Elias Hicks.

Another leader, Primus Martin, had a home in Guinea Town that remains today; ceramic fragments reveal communal dining was prevalent, suggesting he was of higher status. Many in the community owned small farms but worked for elites who had large properties along the Hudson River. The community gradually dissolved after a man named John Hackett purchased much of the land. Nearly two dozen properties were recommended as state and national historic places by the New York State Board of Historic Preservation in December 2017.

Timbuctoo was an African American farming colony in the town of North Elba, just a few miles from Lake Placid in the Adirondacks. It was one of the northernmost free Black communities in New York State, but it was also one of the most significant. In 1846, New York enacted a law stating that Black homeowners could vote only if their real estate was valued at $250. Abolitionist Gerrit Smith gave away 120,000 acres of land to 3,000 Black New Yorkers, creating communities including Negro Brook and Blackville in the North Country. Many moved here to escape slave catchers, who would capture fugitives and sell them back into slavery.

Many residents of Timbuctoo were recruited by Frederick Douglass himself alongside Smith. Residents were expected to have high moral character and high self-restraint. John Brown, who would lead the famous raid on Harper’s Ferry, moved to the area to support Timbuctoo’s development. However, the community struggled since many residents were inexperienced farmers and could not handle rural living. By 1871, just two families remained in the settlement. Notable residents included Lyman and Anne Epps, whose family lived in the area for over a century, and William Appo, who fought at the Second Battle of Bull Run.

Next, check out 33 Black Historic Sites in NYC!

Subscribe to our newsletter