How to See the Liberty Bell...in Queens

A copy of the famous American bell can be found inside a bank, which itself is modeled after Independence Hall!

Get a first look at new spaces and restored galleries in the museum set to reopen this April!

The Frick Collection is famously a house museum—the actual residence of American industrialist and businessman Henry Clay Frick. But as such, it’s also a neighborhood museum, one that fits serenely into the elegant Upper East Side area that it calls home. “The Met is admired, but the Frick is beloved,” says architecture critic Paul Goldberger, comparing the Frick to New York City’s largest and wealthiest museum. The Frick is New York's only world-renowned neighborhood museum.

For nearly five long years, the Frick closed for a $330 million renovation, its grounds torn up, its buildings covered in scaffolding and netting, and its treasures moved a few blocks uptown to the Brutalist Breuer Building. Many Frick admirers were appalled. But Xavier F. Salomon, the Frick's Deputy Director and Peter Jay Sharp Chief Curator, said at the time that “re-presenting the collection in Breuer’s concrete shrine is an unparalleled opportunity to see the Frick’s holdings in a new light.” How right he was! The austerity of Breuer’s concrete shrine somehow let the opulent beauty of the Frick holdings dazzle individually. We all saw them in a new light.

Now the treasures have been returned home, the magnolia trees on the front lawn are set to bloom, and all seems right with this small part of the world. The Frick Collection opens to the public on April 17th.

Saturday, May 17th at 10AM ET: Gain access to the newly renovated Frick Collection on an exclusive guided tour before opening hours, including a first look at new galleries!

Open to Untapped New York Members at the Insider tier and higher. Join today for access to exclusive experiences and discounts!

If you approach the Frick from the North, walking down Fifth Avenue, you’ll glimpse Jean-Antoine Houdon's six-foot Diana the Huntress, restored to her rightful corner overlooking Central Park. She stands almost immediately across from the memorial designed by Bruce Price, with sculptures by Daniel Chester French, designed to honor eminent architect Richard Morris Hunt, whose Lenox Library, a neo-classical beauty, was demolished to build the Frick mansion.

Stroll past the block-long welcoming banner, featuring Frick stars like Sir Thomas More and Vermeer's Mistress, and turn the corner onto 70th Street. The lovingly restored entrance awaits.

(Left) 70th Street entrance to Frick Villa, pediment sculpted by Sherry Edmundson Fry and carved into stone by Attilio Piccirilli

Lounging above the Frick pediment is Audrey Marie Munson, the country's most successful early 20th-century model, sculpted by Sherry Edmundson Fry and carved into stone by Attilio Piccirilli. Said to have had a perfect form, Munson is the golden woman protecting the Maine monument on Columbus Circle, fertile Pomona at Grand Army Plaza, Beauty at the New York Public Library, Civic Fame topping the Manhattan Municipal Building, and the Spirit of Commerce on the approach to the Manhattan Bridge.

The front door opens to a well-lit, almost palatial entrance hall, startlingly different from the dim, somewhat claustrophobic space of old. The Frick's comprehensive renovation and expansion project was led by Selldorf Architects, joined by Beyer Blinder Belle as executive architect. The museum-wide enhancements encompass 27,000 square feet of new construction and 60,000 square feet of renovated or repurposed space and promise “unprecedented access” to the landmarked 1914 building.

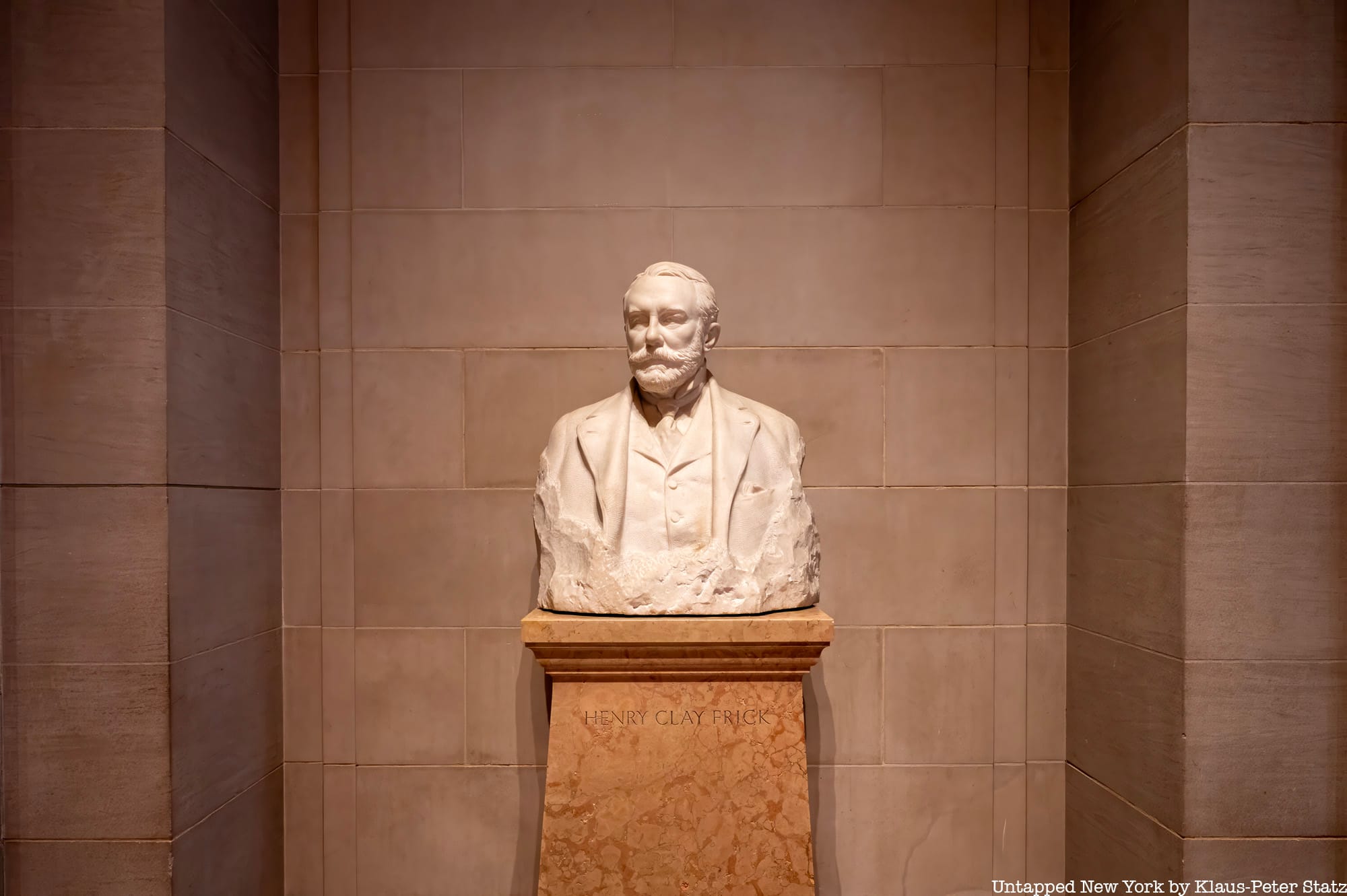

Meanwhile a bust of Henry Clay Frick keeps an eye on things to the right.

Visitors spread out in different directions, many heading for the grand staircase with the magnificent organ. The staircase’s ornate wrought-iron balustrade was inspired, appropriately, by the dean’s staircase, designed by Jean Tijou, in St. Paul’s Cathedral in London.

Instead, I head for my favorite room, the Living Hall, which Salomon calls “the holy of holies." Holbein the Younger's portraits of Sir Thomas More on the left and Sir Thomas Cromwell on the right, on opposite sides of the mantel, are re-hung precisely as Henry Clay Frick had hung them. Between them, El Greco's St. Jerome presides from above the fireplace.

At Frick Madison, More and Cromwell also faced each other, but on much nearer terms. Getting very close to these two portraits was one of the thrills of the uptown location. Of the two, Holbein’s More is considered the superior painting, probably the greatest Holbein in America, says Salomon.

On the opposite wall of the Living Hall is Giovanni Bellini’s “St. Francis in Ecstasy,” which many regard as the finest painting at the Frick. It may also be the most viewed painting at the Frick, a conclusion officials reached because of the frequency with which they must replace the carpet. (The violet carpet is new, of course.)

In honor of Helen Clay Frick’s practice of placing fresh flowers in the galleries, the Frick commissioned contemporary artist Vladimir Kanevsky to create suitable porcelain flowers and botanicals. These artichokes, which thrive in a Mediterranean climate, are probably a fitting tribute to Bellini, whose own plants in that austere landscape are so detailed and accurately drawn that modern botanists can identify nearly all of them, however obscure.

Although Henry Frick had originally disliked Bellini's St. Francis he grew to admire it so much that he habitually sat before it to read, perhaps also pondering his life which had involved substantial violence and tragedy.

Some of the most architecturally admired sections of the Frick Mansion were built after Frick's death. The Garden Court, for example, had been created by classicist John Russell Pope, the architect chosen by Helen Clay Frick to convert the house to a museum, as her father had instructed. Pope proposed clearing the former courtyard and enclosing it under glass, adding palms, plants, and a sunken pool and fountain. The result is the sublime Garden Court.

Despite being one of the most distinguished architects of the early 20th century, Pope was harshly criticized for his classicism, which was out of fashion. His design, for example, for the Jefferson Memorial (beloved today) was called a servile sham, decadent stylism, and, grimly, a cadaver. He was even contemptuously called the last of the Romans, intended as a profound insult.

But Helen Clay Frick stood by him.

Upstairs on the second floor, ten rooms and five additional passages are open to the public for the very first time. These spaces, previously used for museum offices, were part of the original Frick residence. Now converted into galleries and two period rooms, these additions have increased exhibition space by 25 percent.

The second-floor galleries focus on the special collecting interests of Frick family members and significant gifts that have been made to the museum. In Henry Clay Frick's original bedroom, now called the Walnut Room, a selection of portraits are on view. In his daughter Helen's bedroom, her contributions to the institution and her love for early Italian Renaissance paintings are acknowledged by the display of works by Cimabue, Piero della Francesca, and Paolo Veneziano. Additional collections now on permanent display include gifts of rare portrait medals, French faience ceramics, porcelain, and clocks and watches.

Two second-floor rooms have been restored to reflect their original uses. These include the Frick family’s Breakfast Room and the Boucher Room. The Boucher Room, so named for the artist (François Boucher) who painted the decorative panels on the walls, was orignally the private sitting room of Adelaide Childs Frick, Henry's wife. Frick acquired the room from a dealer in 1916 for half a million dollars.

When the home became a museum in the 1930s, Mrs. Frick's boudoir was dismantled and moved downstairs into a butler's pantry while the second floor room was converted into a director's office. In the most recent renovation, the room has been restored to its original second-floor location, where its windows overlook Fifth Avenue and Central Park.

The Frick's extraordinary renovation will serve New Yorkers well for decades to come. As Salomon said at the crowded March 25th press presentation, referencing Lampedusa's Il Gattopardo: You have to change everything so that everything stays the same—a principle worth pondering in this city of constant change.

And perhaps nothing at the Frick exemplifies this more than Russell Page's now beautifully restored viewing garden, the object of such bitter battles in 2014, when the Frick proposed its demolition. Charles Birnbaum, president of the Washington D.C.-based Cultural Landscape Foundation, called Page’s design a “master class in restrained minimalism,” a model of precision and beauty, giving an illusion of size to a postage-stamp-sized garden. Designed as a temporary space in 1977, the garden has established itself as a crucial component of the Frick's evolving essence.

And also as a survivor.

The Frick Collection opens to the public on April 17th! You can book tickets to visit online.

On May 17th, Untapped New York Members are invited on a special private tour of the museum before it opens for the day! This exclusive tour is open to members at the Insider tier or higher, and tickets go on sale May 3rd at 12 pm ET. Not a member yet? Join today for access to exclusive experiences, tour discounts, an on-demand video archive of 300+ webinars, and more!

Saturday, May 17th at 10AM ET: Gain access to the newly renovated Frick Collection on an exclusive guided tour before opening hours, including a first look at new galleries!

Enjoy a sneak peek in the gallery below!

Next, check out 10 Gilded Age Mansions You Can Visit in NYC

Subscribe to our newsletter