Last Chance: The Annual Orchid Show Soars at the New York Botanical Garden

The vibrant colors of Mexico come to NYC for a unique Orchid Show at NYBG!

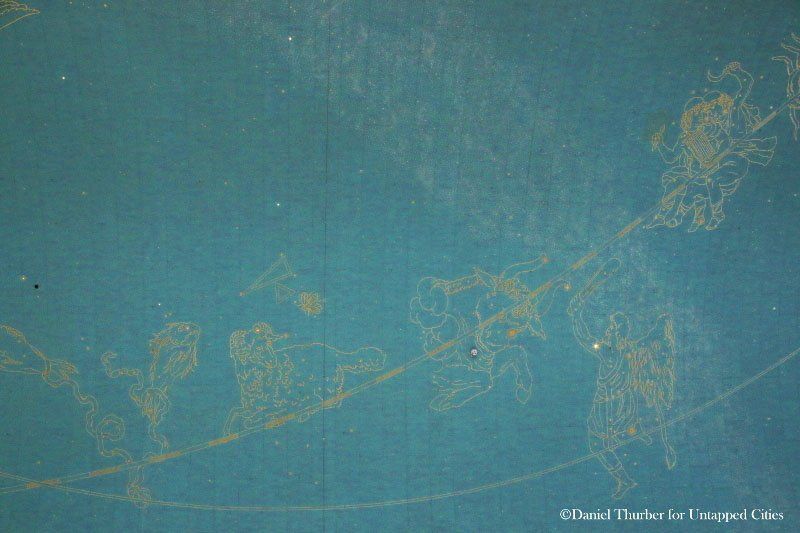

Arguably one of the most famous ceilings in the world, the mural high above Grand Central Terminal’s main concourse is as fascinating as it is awe-inspiring. While much has been written about it, one detail that seems to be overlooked is hidden in plain sight, the proverbial fly-on-the-wall. Or in this case, a fly on the ceiling.

The mural depicts a section of the sky visible to the Northern horizon during the wintertime. As one of the busiest, brightest, and most recognizable areas of the celestial sphere, it’s no wonder why this particular area was chosen for the mural. The major constellations it depicts (Pegasus, Aquarius, Pisces, Aries, Taurus, Orion, Gemini, and Cancer) are familiar to almost everyone whether through an interest in astronomy, history, mythology, or astrology.

A quick glance at a star atlas will tell you much about these constellations. You’ll even find details about the triangles over Aries’ head (a constellation called Triangulum), but what you won’t find much about is the small insect hovering just over Aries’ rump. It’s not in any modern star guides, and it wasn’t in any back in 1912 when the mural was painted. So where did it come from?

Detail from ‘Atlas Maritimus & Commercialis’ by Nathaniel Cutler and Sir Edmond Halley (1728)

The constellation is typically called “Musca Borealis” or “the Northern Fly”. Considered a ‘modern’ constellation (that is, it wasn’t one of the 48 constellations laid out by Ptolemy in the Second Century AD), Musca Borealis first appeared in 1613 on a celestial globe designed by Flemish astronomer Petrus Plancius, who referred to it as “Apes” or “the Bee.” The four stars that made up Apes were familiar to astronomers prior to this but were generally considered part of the Aries grouping and had never been specifically set aside on their own.

It’s not surprising that Plancius used them to make a new constellation as this was something of a hobby of his. Over his lifetime, Plancius introduced 21 new constellations, many of which are still recognized by the International Astronomical Union (IAU).

In 1624, in a work called “Usus Astronomicus,” German astronomer Jakob Bartsch included the Fly (although he changed the name to “Vespa”, or “Wasp”). By the end of the 1600s this small constellation had become common in star charts, now typically referred to as “Musca,” Latin for “Fly.”

The name “Musca” led to some confusion with another constellation of the same name, this one in the southern hemisphere near the celestial South Pole. Just to add to the confusion, the southern Fly, also introduced by Plancius, was initially called “Apis.” To clear this up the northern insect became “Musca Borealis,” with its southerly counterpart known as simply as “Musca.”

The Northern Fly would fall out of favor with astronomers, perhaps owing to all the confusion. By the end of the nineteenth century it had essentially disappeared from the charts. So how did it end up on the ceiling at Grand Central?

To try and answer that we have to piece together the design of Grand Central’s mural. To construct the mural an astronomer at Columbia University, Dr. Harold Jacoby, was consulted. The artist in charge of the actual design was Paul Helleu, a French artist and engraver, with the actual painting being done by Charles Basing, of the Brooklyn-based Hewlett-Basing Studio.

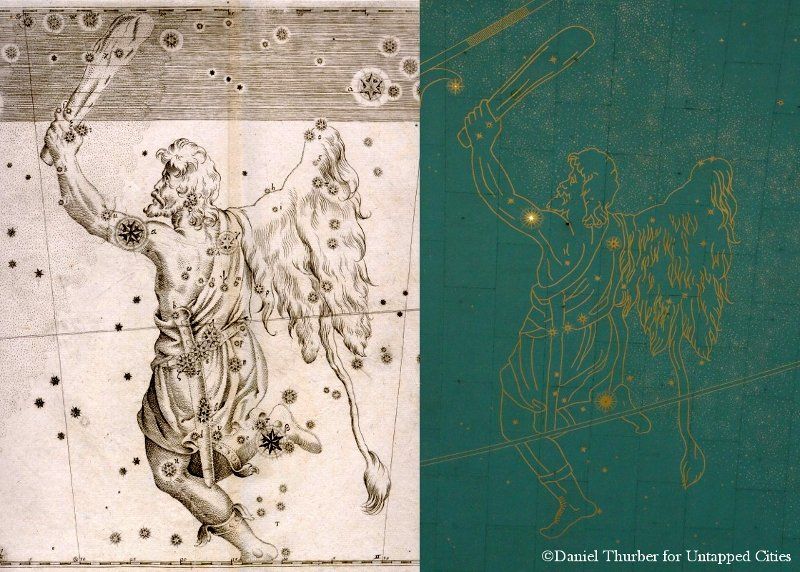

All of the individual constellations (with the exception of the “Fly”) were taken, almost line for line, from the 1603 celestial atlas Uranometria (literally “Measuring the Sky”) by German astronomer Johann Bayer. Also referred to as the “Bayer Atlas, the Uranometria is significant for two reasons; first: it introduced the labeling of stars with Greek letters, a practice still in place today, and second: it was the first celestial atlas to use such detailed and artistic designs for the constellations.

Orion as he appears in the ‘Uranometria’ versus the Grand Central mural. ‘Uranometria’ image from Wikicommons, courtesy of the United States Naval Observatory Library

The Bayer Atlas does depict the stars that would make up Musca on the same page as Aries, but doesn’t label them at all, much less form a constellation from them. Appearing in 1603, the Bayer was 10 years too early to depict the stars as their own constellation and put them with Aries, as had been done for centuries. If Musca wasn’t in the Bayer, like all the others on the ceiling, how did it end up in the mural?

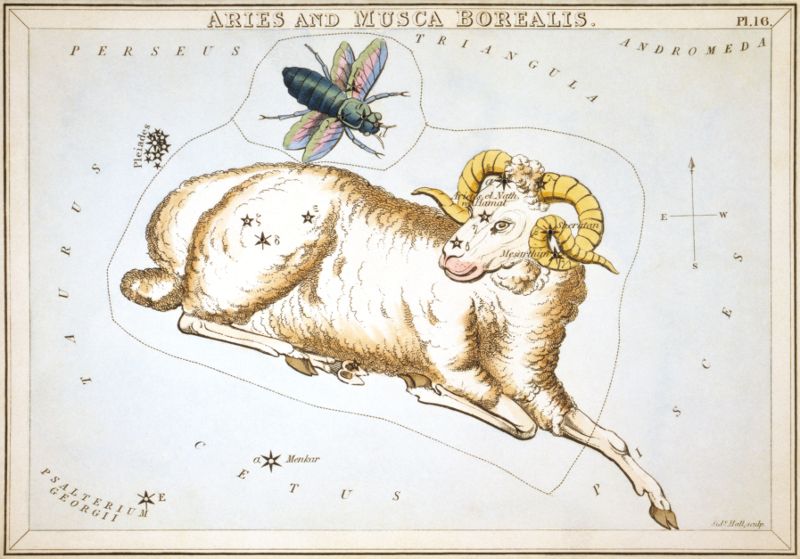

Taking a bit of a logical leap, it appears that the mural design might have also referenced a later celestial atlas for the design of the Fly: either the 1820 Celestial Atlas by Scottish professor Alexander Jamieson or the 1824 Urania’s Mirror which is a more colorful version of Jamieson’s work printed as a set of constellation cards. The reason for this conclusion is that Jamieson was the first person to depict the Fly as having two sets of wings. Previous versions only showed one. The version on the ceiling has two.

Musca Borealis as it appears in Urania’s Mirror. Note the two sets of wings. Image from Wikimedia Commons

While Jamieson’s book came first, the Mirror is much more famous, so it is likely the Fly on the ceiling was influenced by the card. But why this single, small figure would be added to a design otherwise entirely sourced from Bayer is unknown.

By the latter part of the nineteenth century, Musca Borealis had fallen out of favor with the astronomical community. Writing in 1899, Richard Hinckley Allen said that while “the constellation has been retained in some popular astronomical works” it is “not figured by the scientific Argelander, Heis, nor Klein, nor recognized in the British Association Catalogue.” When the IAU met at their first General Assembly in 1922, they declined to declare Musca an official constellation, officially returning the stars to Aries.

Uncover more secrets of Grand Central Terminal on one of our upcoming walking tours!

Tour of the Secrets of Grand Central Terminal

Next, check out the Top 10 Secrets of Grand Central Terminal. Get in touch with the author at Bookworm History.

Subscribe to our newsletter