Fiber Arts Take Over a Former Seaport Warehouse in NYC

See waterfalls of fabric, intricate threadwork, massive tapestries, and more!

In celebration of the 100th anniversary of Grand Central Terminal, we will be exploring all aspects of the terminal, from its most famous attributes to its hidden treasures. Last week, we showed you what Grand Central could have been if other architects had built it. Now, we will explore the City that was created alongside Grand Central Terminal

For the past century, New York City has been graced by Warren & Wetmore’s Beaux Arts masterpiece. However, most people are unaware that Grand Central Terminal does not stand on its own. The original plans by Reed & Stem, along with William John Wilgus, called for an entire city to accompany their train station.

Terminal City was to include a new home for the Metropolitan Opera and the National Academy of Design, as well as a 20 story post office building, office space, and hotels. While this vision was not realized, Terminal City did become a reality after many revisions. One of the most important aspects of the complex was its grand hotels, which complemented Grand Central both in design and purpose. We explore those hotels designed by Warren & Wetmore below.

Bowman Room in the Biltmore Hotel. Photo via Library of Congress, Gottscho-Schleisner Collection

The Biltmore was the brainchild of Gustav Baumann and was the fourth grand New York City hotel to be designed by Warren & Wetmore. It was described as being sumptuous and magnificent and its design ensured that at twenty-six stories it still maintained a harmonious relationship with the rest of Terminal City. A palm court, grand ballroom, Italian garden, and private arrival station at Grand Central ensured that the Biltmore would be in a class of its own. Its name lured the likes of Zelda and F. Scott Fitzgerald to honeymoon there and F. Scott Fitzgerald and J.D. Salinger to incorporate it hotel into their stories.

The hotel had its own arrival station within the terminal, nicknamed “The Kissing Room,” with elevator access to the lobby, a private elevator served only the presidential suite, and a palm court, which echoed the design of the main concourse at the Terminal. The grand ballroom occupied the hotel’s 22nd floor. Called the Cascades, it was the home of the conductor Bert Lown in its early years. An Italian garden was situated between the north and south towers. In the winter months, it was transformed into an ice skating rink.

The hotel was also historically important. Henry Ford tried to broker an end to the First World War there in 1915. On August 4, 1916, the Treaty of the Danish West Indies was signed there by Danish Minister Constantin Brun and Secretary of State Robert Lansing, giving the Danish West Indies (now U.S. Virgin Islands) to the United States for $25,000,000 in gold. Also, from May 6 to May 11, 1942, 600 delegates and Zionist leaders from 18 countries attended the Biltmore Conference, which resolved that British Mandate Palestine be established as a Jewish Commonwealth.

In August 1981, the Biltmore was gutted and from its steel frame was transformed into Bank of America Plaza, or 335 Madison Avenue. A small reminder of the building’s past is still present at 335 Madison Avenue. The clock that once hung at the entrance to the Biltmore’s palm court, where people famously would meet and its piano can still be found in the lobby of 335 Madison Avenue.

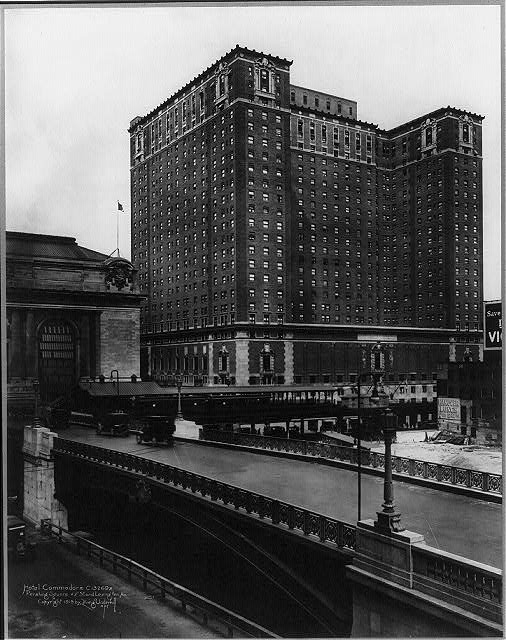

Photo via Library of Congress by Irving Underhill

The Commodore Hotel opened on January 28, 1919 and it was named after the eponymous Commodore, Cornelius Vanderbilt. The hotel had 2,000 rooms when it was built, and boasted that it was not only the world’s largest but also possessed the world’s most spacious lobby as well. A never realized expansion would have enshrined the hotel’s claims by doubling its size to 4,000 rooms.

The Grand Hyatt New York Hotel at Grand Central in Manhattan.

Through the 1960s, the hotel was very successful. Unfortunately, the 1970s brought bankruptcy to the railroad company and the hotel was sold off. Donald Trump purchased the hotel but its terminal city history proved no match for Trump. In 1980, Gruzen & Partners and DerScutt and were brought in to redesign the building. The Commodore was gutted, reclad in glass, and re-inaugurated as the Grand Hyatt New York. The hotel’s original masonry smokestack is still visible in its new state.

Photo via Library of Congress by Detroit Publishing Co.

In 1912, Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt I commissioned Warren and Wetmore to construct a hotel at 34th Street and Park Avenue. Alfred Vanderbilt was the son of third son of Cornelius Vanderbilt II and grandson of Commodore Vanderbilt and he grew up in this stately mansion (whose remnants still abound). While the facade was restrained, with terra cotta flourishes, its interior was full of amenities and state of the art technologies, including pneumatic tubes. The Della Robbia Room was located in the hotel’s basement and was architecturally noted for its Gustavino ceiling.

Dela Robbia Room

Vanderbilt had the top two floors of the hotel transformed into a private house for his family. He lived there until 1915 when he tragically died on the Lusitania after giving up his life jacket. Howard Hughes, Ring Lardner, and the famed Italian opera singer Enrico Caruso (who took over Vanderbilt’s suite) all took up residency in the hotel over the years.

In 1925, the Vanderbilts sold the hotel and in 1967, the hotel was converted into a mixed-use building (upper floors apartments and lower floors offices). In 1966, the hotel’s new owners began to remove its fanciful terra cotta and the architects Schuman, Lichtenstein & Claman reclad the lower portion of the building. All was not lost. In 1994, the Della Robbia Bar was designated an interior landmark by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. Some of the terra cotta ended up in the sculpture garden at the Brooklyn Museum, and the majority of the hotel’s facade is still in its original state (originally the plans called for its entire facade to be redesigned).

Photo via Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Co.

Warren & Wetmore designed this hotel at 120 Park Avenue for August Belmont, in 1906. Belmont was responsible for the creation of the Belmont Park Racetrack and in 1902, founded the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT). The hotel was 292 feet high and possessed a private subway entrance for Belmont’s personal subway car, the Mineola. In 1928, the hotel closed its doors and the building was remodeled as an office building and was connected to Grand Central Terminal. The building was demolished shortly thereafter and essentially forgotten. A number of interesting buildings have since been located at 120 Park Avenue, including the Philip Morris Building.

Terminal City was an integral aspect of Reed & Stem’s winning design for Grand Central Terminal. They envisioned a terminal that would be the focal point for a new neighborhood. While some of their proposed tenants never relocated, a new neighborhood was born. It was influenced by the City Beautiful movement and was a city planner’s dream. Hotels and office buildings were constructed to complement one another and Grand Central. Even though little is left of the original Terminal City, what was begun with these hotels and their accompanying office buildings would inspire future architects and planners including those who worked on Rockefeller Center. That is why Terminal City deserves at least some of the spotlight flooded upon its namesake terminal.

Join us for an upcoming tour of the secrets of Grand Central Terminal:

Tour of the Secrets of Grand Central Terminal

Next, read about the Top 10 Secrets of Grand Central Terminal.

Subscribe to our newsletter