How to See the Liberty Bell...in Queens

A copy of the famous American bell can be found inside a bank, which itself is modeled after Independence Hall!

Philip Johnson with Gregory Ain in the house Ain designed for the Museum of Modern Art, 1950. Photo courtesy of The MoMA

Philip Johnson with Gregory Ain in the house Ain designed for the Museum of Modern Art, 1950. Photo courtesy of The MoMA

Back in the first half of the 20th century, when giants in art and architecture walked the earth, architect Gregory Ain joined the ranks of the architectural elite, including Buckminster Fuller, Marcel Breuer, and Frank Lloyd Wright, when the Museum of Modern Art invited him to design an exhibition house.

The house was designed—exhibited in MoMA’s garden to great acclaim—and then lost. That loss is the subject of a tiny but riveting exhibition, This Future Has a Past, mounted by Anyspace at the Center for Architecture in New York after being shown at the Venice Architecture Biennale in 2016.

Image courtesy of The MoMA

Other MoMA houses were carefully dismantled and moved (Marcel Breuer’s 1949 House in the Garden, for example, was bought by the Rockefellers and rebuilt on Laurence Rockefeller’s estate in Pocantico), but Ain’s house ended in oblivion. MoMA’s extensive archives are silent on its fate.

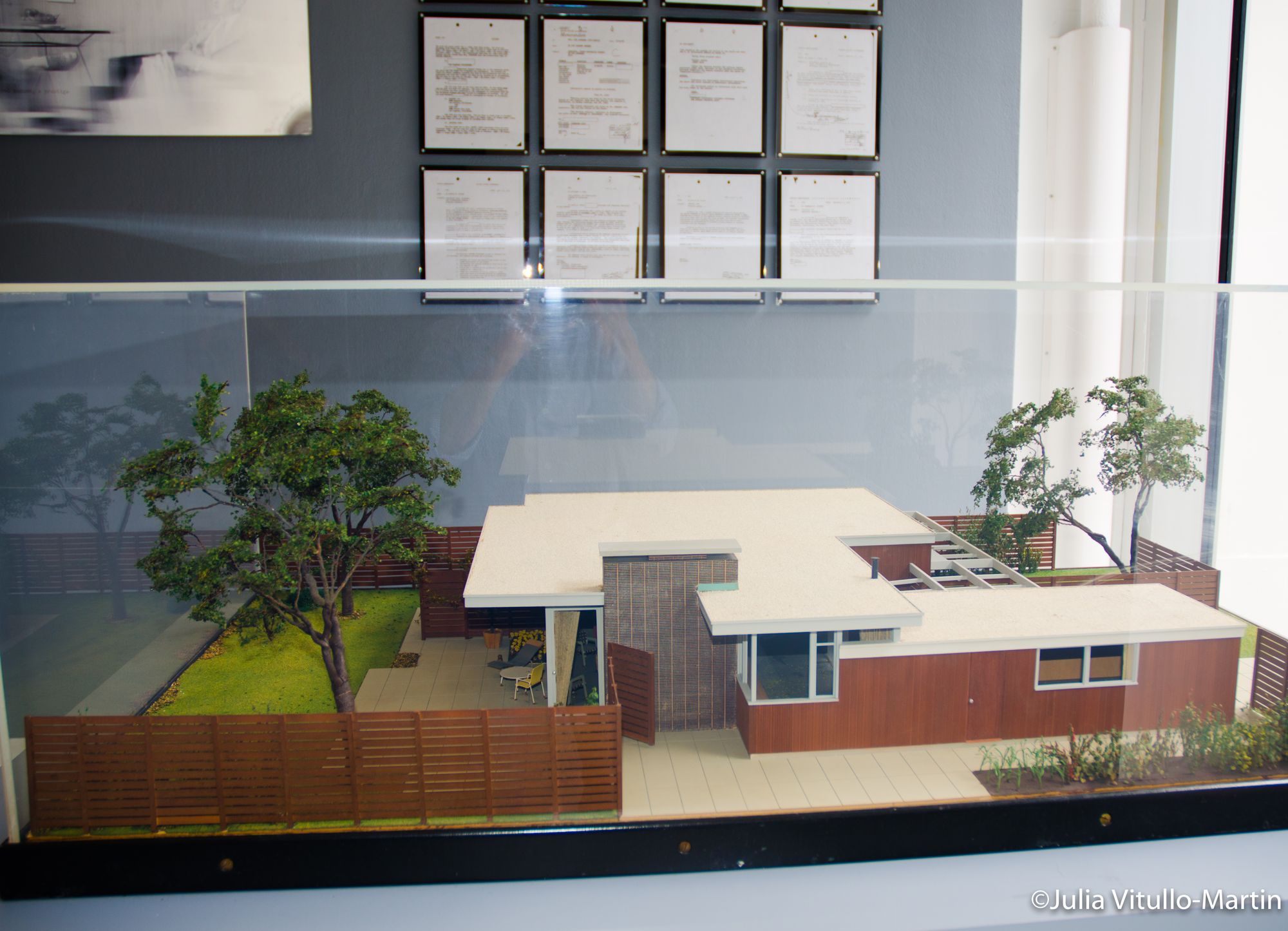

Gregory Ain’s exhibition house for MoMA, 1950, at the Center for Architecture

Gregory Ain’s exhibition house for MoMA, 1950, at the Center for Architecture

The Ain story is a sad one: great promise, high ideals, technical brilliance, renowned friends and students (Frank Gehry studied with him), followed by a mixture of the Red Scare (headlined the New York Times), mental and physical illness, and death in obscurity. The exhibit helps bring Ain’s work back to life and reminds urbanists of the principled ideals that were once fundamental to the public conversation about architecture.

MoMA commissioned eminent architects to build simple, modernist houses suitable for moderate-income families, a mission to which Ain had long been devoted to. He believed in constructing a “social landscape” says Anthony Fontenot, a professor of architecture who wrote his doctoral dissertation on Ain, integrating architecture, landscape, and planning. Ain’s new approach to shared urban space included day care facilities, parks, and health clinics, addressing “the common architectural problems of common people,” wrote his biographer, Anthony Denzer.

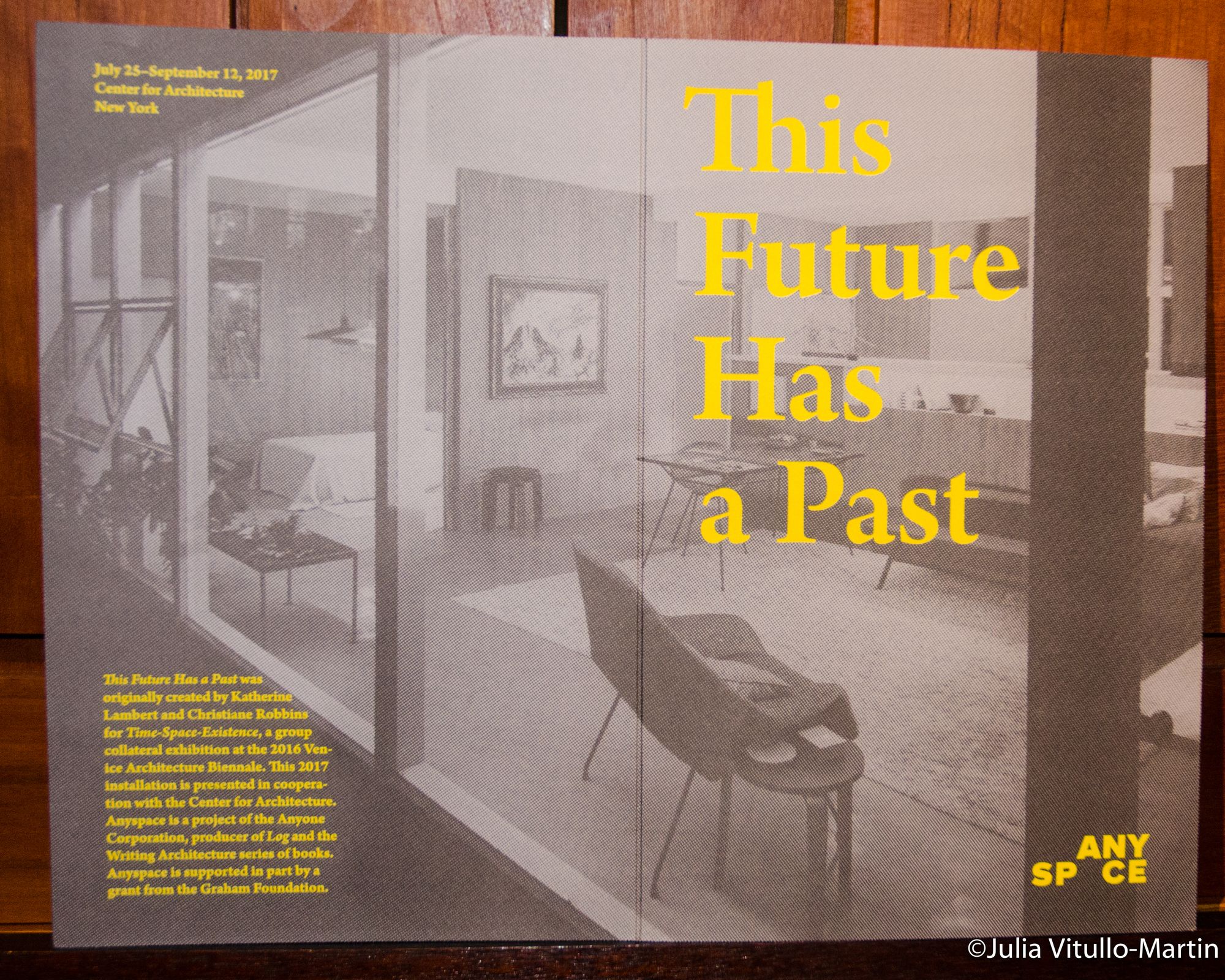

This Future Has a Past brochure

This Future Has a Past brochure

His work, says the exhibit brochure, “offered a promising model of democratic planning for the postwar American city,” but a plan that was essentially blackballed by the Federal Housing Administration, which preferred to support typical suburban tracts. Ain, meanwhile, adapted new prefabrication techniques and home-building practices that kept costs down on his innovative designs, such as the Community Homes Cooperative of the late 1940s, which the FHA refused to support in part because the plan called for racial integration.

FBI director J. Edgar Hoover said he was “the most dangerous architect in America.” His radical ideas are now mainstream.

“This Future Has a Past” is now on display at the Center for Architecture (536 LaGuardia Place). Upcoming Event at Center for Architecture: Who Was Gregory Ain? on September 7th.

Next, check out Discover the Historic Role of the 7 Train at the New York Transit Museum in NYC and 10 Frank Lloyd Wright Buildings in and Around NYC.

Julia Vitullo-Martin is a Senior Fellow at the Regional Plan Association. Get in touch with her @JuliaManhattan.

Subscribe to our newsletter