Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

Did you know that European immigration helped the flavor manufacturing industry flourish in New York City? Or that Chelsea Market used to be the factory complex for the National Biscuit Company, where the Oreo was created? Historian Nadia Berenstein discussed all of this during her lecture at Making It Here: A Local History of Flavor, hosted by the new Museum of Food and Drink‘s Mofad Lab yesterday evening.

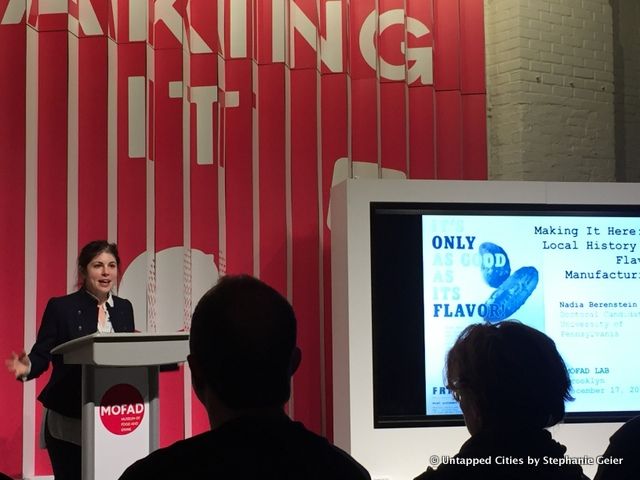

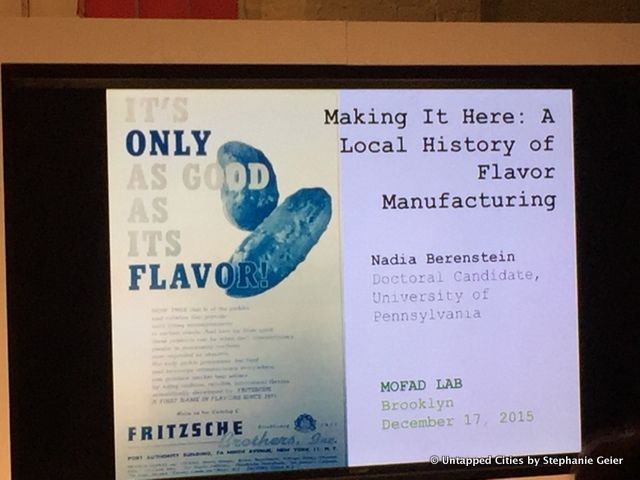

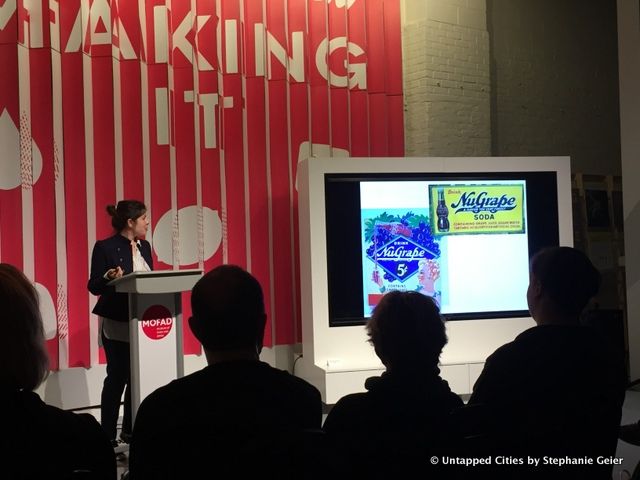

Nadia Berenstein starting her presentation

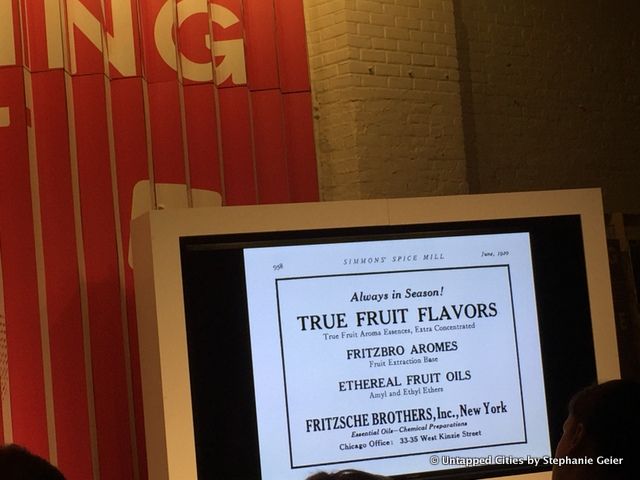

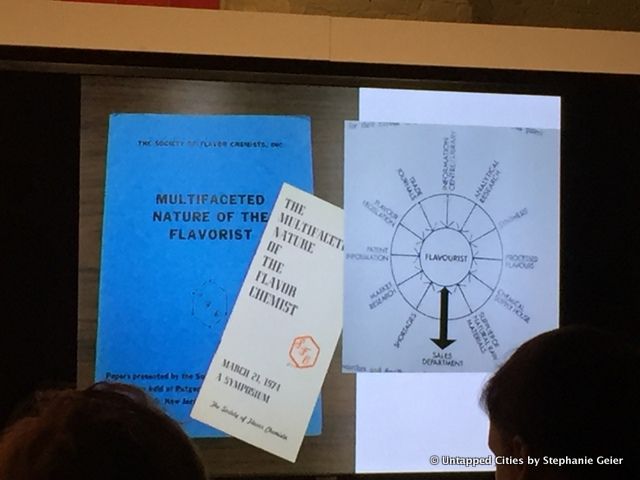

During the event, Ms. Berenstein discussed the local history of the flavor manufacturing industry, covering topics from the early essential oils firms in Lower Manhattan and showing the audience vintage menus and surprising food advertisements.

Ms. Berenstein started the talk with a story from the recent past: the mysterious maple syrup smell in New York City. The mysterious scent wafted along the streets of West Manhattan starting in 2005, intriguing pedestrians as to its origins and capturing news headlines. It turned out that the scent derived from a chemical associated with maple syrup and caramel that was being manufactured in the inconspicuous Frutarom Factory in North Bergen, New Jersey.

She then went on to discuss the factors that shaped such an industry, starting in Lower Manhattan in 1830. During this time, clustered firms caused the area to smell of cargo and other unappealing scent, and she showed the audience a map of the essential oils firms area near Pearl and Water streets.

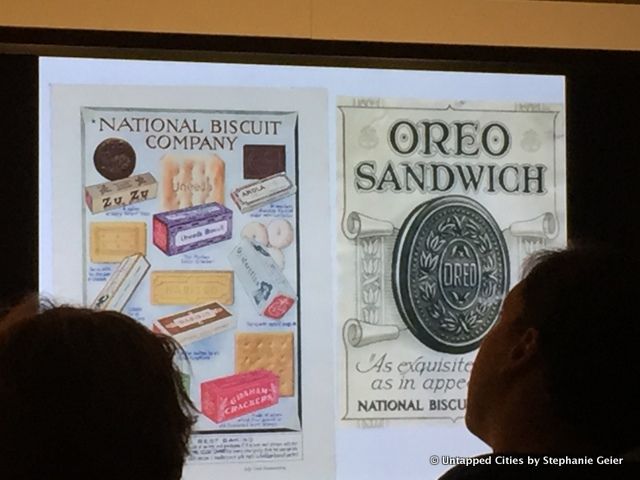

Thanks to a large European immigrant population with the necessary skills in New York City at the time, these businesses could run appropriately. The expansion of the sugar manufacturing company also led to new opportunities for flavor consumption, and New York City was a major food manufacturing company before World War I. Ms. Berenstein showed the audience images of gum ball and chocolate factories, advertisements for the National Biscuit Company (Nabisco) once headquartered in today’s Chelsea Market.

She also described relevant organizations like the Aroma Club and FEMA (no, not the FEMA you’re probably thinking of-it’s the Flavor and Extract Manufacturers Association). She then mentioned some companies with interesting backstories. For instance, the FCC once told the NuGrape Soda company that its product had too many additives to be called “grape.” The Virginia Dare company, which now produces flavoring, started out selling wine, but then came up with a way to de-alcoholize its wine and instead use the alcohol to make extracts.

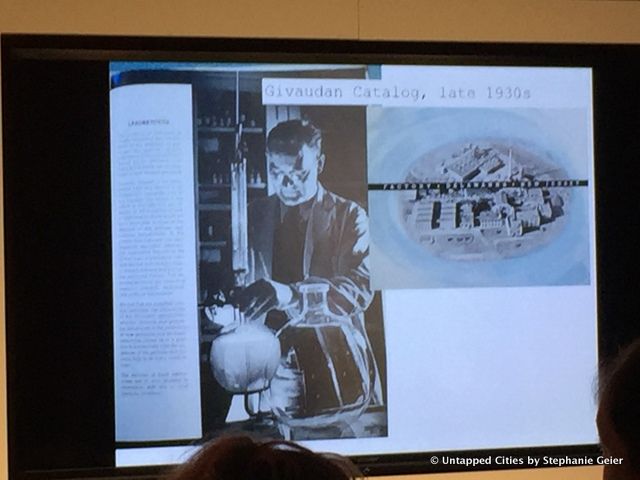

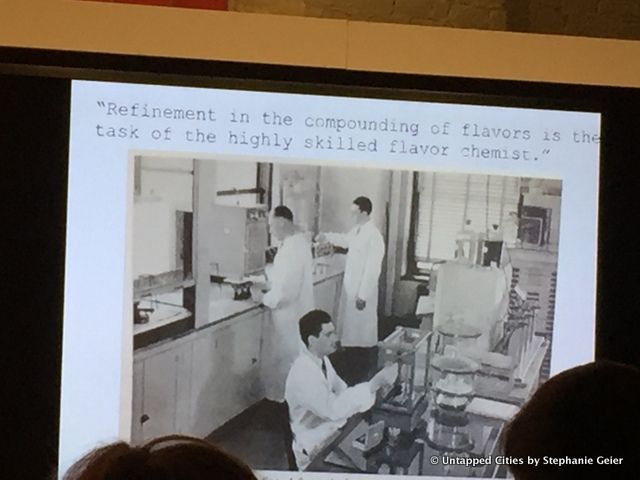

By the arrival of the 1930s, flavoring companies needed both a lab and factory to function well, and the mid-1900s ushered in what one historian called the Golden Age of processed food, which was a period of a boom in new technology and pre-packaged food fueled in part by WWII research.

On a quirkier note, Ms. Berenstein has actually interviewed flavor chemists from this period; one mentioned how he would sit at the front of the Long Island Railroad if he returned from work smelling fruity and delicious, and would sit at the back if he spent the day working with meat and sulfur-based scents.

She ended her lecture talking about the present-day flavor manufacturing industry, pointing out that New Jersey actually has the highest concentration of flavor companies today. A Q&A session followed, and Ms. Berenstein answered questions on topics like crossovers between the flavor and pharmaceutical industries, connections between chemical warfare research and chemical flavoring, and whether synthetic food coloring developments mirrored those of synthetic flavors.

When asked about her opinion of the future of the food flavoring business, she noted that people tend to divide food into those that are locally grown and those that are unhealthy and manufactured. However, she doesn’t think there needs to be such a divide for an improved food industry.

Ms. Berenstein also told us a few extra fun facts that New York City lovers might find interesting after the talk: Amyl Acetate, the flavor associated with fake bananas in candy, was discovered by a New Jersey flavor chemist right outside of New York and is actually found in real bananas. In addition, Post’s Alpha-Bits cereal was inspired by an Italian-American food scientist’s memories of alphabet pasta he ate as a child.

The exterior of the Mofad lab in Williamsburg

The talk took place at the Museum of Food and Drink’s (Mofad) new, 5000-square foot Mofad Lab in Williamsburg. Because of the small space, it can only host one exhibition at a time (its current one, Flavor: Making It and Faking It runs until February). The museum’s executive director, Peter Kim, compared the venue to a “test kitchen” and the future full-fledged museum, which the Mofad team hopes will be about 30,000 square feet, to a restaurant.

Though small, the venue is nicely set up and well-managed. Capturing the museum’s sprit, staff members served flavored soda before and after the talk. There was also some pretty eccentric merchandise on display, such as edible chemistry sets, black pepper scented oil, and “Miracle Berry.” Scroll down for more images of the lab:

Dave Arnold actually conceived the idea for Mofad in the early 2000s, but the museum itself started to become a reality in 2013 with its pop-up exhibition “Boom! The Puffing Gun and the Rise of Cereal” at the Summer Streets Festival. Mofad, as a certified nonprofit, thus relies heavily on volunteers and donations to continue expanding.

Next, check out The Top 10 Hidden Restaurants in NYC: 2015 Edition and Inside Brooklyn’s Former Pfizer Plant and Its Transformation into Manufacturing Hub. Get in touch with the author @sgeier97

Subscribe to our newsletter