Fiber Arts Take Over a Former Seaport Warehouse in NYC

See waterfalls of fabric, intricate threadwork, massive tapestries, and more!

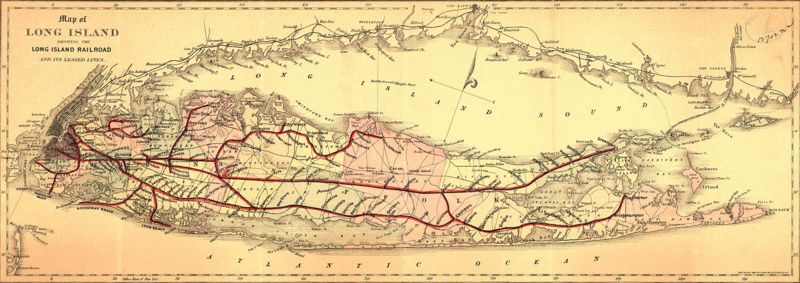

The Long Island Rail Road (LIRR) is one of the oldest railways in the United States. It began life as the Brooklyn and Jamaica Rail Road (B&J), which was incorporated in 1832 to serve a 10-mile stretch between the City of Brooklyn and the village of Jamaica. However, while the B&J was still just in the planning stages, the railroad’s developers had ambitious plans for a train that ran the entire length of Long Island and connected New York to Boston via a ferry from Greenport. It was thought that this route would out-compete the other obvious route through southern Connecticut because that path would have to cross too many wide streams. By contrast, the LIRR does not have to cross any major streams on its way to Greenport.

With the plans in place for an island-spanning railroad, the Long Island Rail Road was chartered in 1834, and the first section between the Brooklyn waterfront and Jamaica opened in 1836. From there, the train tracks expanded eastward, reaching Hicksville in 1837, Deer Park in 1842, and finally Greenport in 1844. Operation between Brooklyn and Greenport began on July 29th, 1844, and reduced the travel time between New York and Boston from nearly fifteen hours down to eleven.

Long Island’s relatively easy terrain and close connection to New York City meant that construction was fast and easy. Upon completion, the LIRR was one of the first major railroads in the United States. It started service only a few years after the country’s first railroad, the Baltimore and Ohio, commenced, and the system was virtually complete decades before the great railroad tycoons would amass their fortunes in the West. In fact, the name “Long Island Rail Road” is the oldest continually-used railway company name in the United States.

During the 1850s and 60s, the LIRR competed with other Long Island railways, such as the New York and Flushing (NY&F) and the Central Railroad of Long Island (CRRLI). The NY&F was the LIRR’s first competitor, beginning operation in 1854 with a route between Flushing and a ferry terminal in Long Island City. The two companies competed for 13 years until NY&F was bought by the LIRR in 1867, eventually becoming the modern-day Port Washington branch. The Central Railroad of Long Island served many of the local villages in Nassau County that the LIRR bypassed on its way to Greenport, but by 1876 the LIRR had bought this railroad as well.

As the 1870s came to a close, the Long Island Rail Road had eliminated all of its major competitors and formed monopoly control over rail service throughout the peninsula. However, the economic recession of 1893-1897 caused ridership to plummet, and by the end of the 19th century, the LIRR itself was bought by the giant Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR). The PRR owned thousands of miles of track from Chicago to New York and for a brief period even operated a special express service from Penn Station to Montauk, fully equipped with dining and lounge cars, for wealthy vacationers traveling to the Hamptons.

In 1905, the Pennsylvania Railroad used some of its mammoth fortune to modernize large portions of the Long Island Rail Road through electrification and grade-crossing elimination projects. The following three decades would be the LIRR’s high point both in terms of service quality and the extent of track miles. Not only did the Pennsylvania Railroad electrify large sections of the LIRR, with the New York City-area electrification project being completed in 1913, but PRR also completed major grade-crossing eliminations. For example, the Atlantic Branch of the LIRR, which runs between Downtown Brooklyn and Jamaica, had 50 grade crossings in 1897. By 1907 a combination of elevated viaducts and tunnels were built and the line became fully grade-separated.

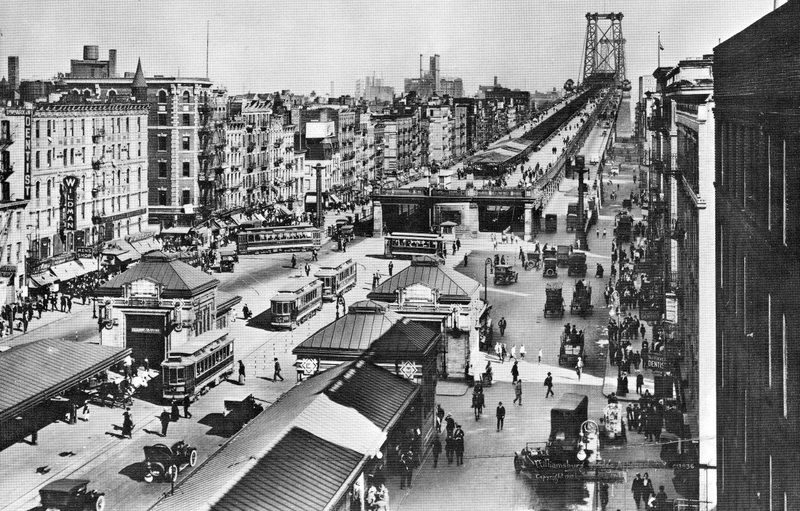

A surprising relic from this era of railroad expansion was the LIRR’s introduction of through-running service into Manhattan via the subway system. Between 1909 and 1917, Long Island Rail Road trains served the Financial District of Manhattan by traveling over the Williamsburg Bridge and into the J/Z subway tunnel to Broad Street. This highly modern level of railway integration exists today only in Tokyo, and it is one of the crowning achievements of their transit system, but an early version of it actually existed in New York almost 100 years earlier.

Unfortunately, beginning in the 1940s, the Long Island Rail Road began to face increasing competition from highways and the automobile, which created a downward spiral of declining ridership, decreasing revenue, and deteriorating service. During the postwar years, at least 22 different branches, spurs, and cutoffs of the LIRR were abandoned, sold off, or even burned down. Some of these branches, like parts of the Rockaway Beach Branch and the Manhattan Beach Branch, were incorporated into the New York City subway system as the A and B/Q trains respectively. However, other major rail corridors were abandoned altogether, like Whitestone Branch that served the Queens neighborhoods of College Point and Whitestone with passenger rail until 1938.

The rapid ascendency of the car after World War II caused cascading bankruptcies for rail companies across the United States. The New York region was not immune from this destruction, and in 1949, the Long Island Rail Road went bankrupt. Although it was still owned by the mighty Pennsylvania Railroad, after the LIRR’s bankruptcy the PRR stopped subsidizing the LIRR. This led to a series of deadly crashes, branch closures, and service reductions throughout the 1950s and ’60s. Even the LIRR’s majestic terminal station in Manhattan, the original Pennsylvania Station, was demolished to build Madison Square Garden. By 1970, the Penn Central Transportation Company, formerly the Pennsylvania Railroad, filed for bankruptcy. Prior to this, the LIRR was acquired by the MTA from the Pennsylvania Railroad in 1965 and incorporated into New York’s regional transportation network

In the decades following the LIRR’s incorporation into the MTA, the railroad has seen a gradual but steady resurgence. By and large, service stopped being cut by the 1970s and in some places even expanded. New electrification projects began in 1968, and by 1987 the Main Line had been electrified from Mineola to Ronkonkoma and the Port Jefferson Branch had been electrified from Hicksville to Huntington. Service slowly increased on the non-electric sections of rail too. For example, in 1963 there was one train running between Riverhead and Greenport per day; in 2018, there were four per day. Today the LIRR is the busiest commuter railroad in the country, serving almost 350,000 daily riders over 11 branches. And throughout its 188-year long history of mergers, expansions, and bankruptcies it has kept its original 1835 name: the Long Island Rail Road.

Curious about the history of the LIRR? Join us for the virtual talk, “When New York Was Long Island: The Past and Present of the Long Island Railroad” led by Gotham Center Writing Fellow and journalist Elizabeth Moore. The talk is free for Untapped New York Insiders (get your first month free with code JOINUS).

Subscribe to our newsletter