After-Hours Tour of the Fraunces Tavern Museum: "Path to Liberty"

Explore a new exhibit inside the oldest building in Manhattan, a witness to history throughout the Revolutionary War Era!

Oysters are working tirelessly for the benefit of New York Harbor after years of over-harvesting and sewage-induced turmoil.

Oysters are one of New York Harbor’s best shots at clean water, as well as one of its best chances at protection from future storm surges. These are the same oysters New Yorkers have done their best to decimate with centuries of pollution and overconsumption. The oysters hold no grudges, however, and have returned to help restore the harbor, even if New York probably doesn’t deserve it.

When Henry Hudson sailed into New York City in 1609, he happened upon one of the world’s most impressive natural harbors. There, Hudson saw whales, otters, turtles, and countless fish. What he could not have seen, however, were the 220,000 acres of oyster beds below the surface on the harbor floor, constituting nearly half of the oysters in the entire world.

The local Lenape, who would open the oyster shells by wrapping the entire oyster in seaweed before tossing them in fire, introduced the ensuing wave of European visitors to Manhattan to the pleasures of oyster consumption. The Dutch, like the English and others who subsequently made their way to New York, loved the tasty bivalves. Oysters quickly became synonymous with New York City, as Mark Kurlansky’s book, The Big Oyster: History on the Half Shell, skillfully outlines. Long before hot dog carts could be found everywhere, oysters were the ubiquitous food items of New York City; the original street meat.

It seemed everywhere an enterprising fisherman looked, they found abundant oyster beds, from outer Long Island to Raritan Bay to Norwalk, Connecticut. In fact, oysters routinely grew to the size of dinner plates in the present-day Gowanus Canal. (And that’s a sentence that gets more disgusting the longer you read it). A first-person account by a Dutch missionary named Jasper Danckaerts recounted in the book Gowanus: Brooklyn’s Curious Canal, describes Gowanus oysters in 1679 as “large and full, some of them not less than a foot long, and they grow sometimes ten, twelve and sixteen together, and are then like a piece of rock.”

Everyone in New York ate oysters. The rich saw them as a delicacy, and the poor enjoyed how cheap they were and not to mention, how easy they were to collect. Oyster taverns popped up all over the city to feed the seemingly insatiable appetite. But, of course, this pace could not endure, and soon the oyster populations faced a multi-pronged threat to their existence.

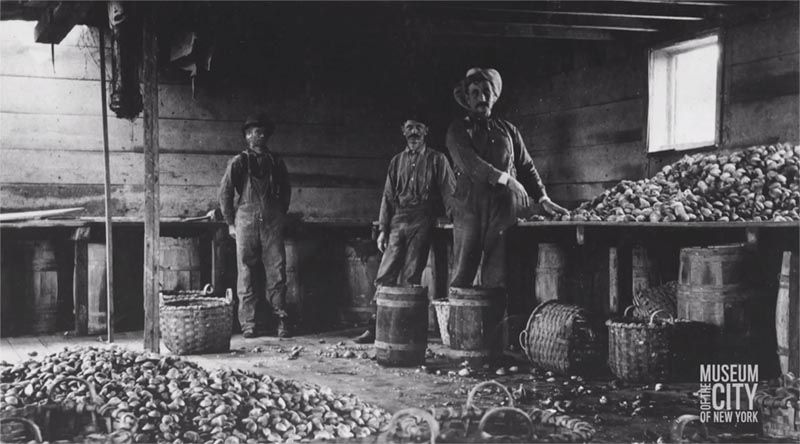

Firstly, they were over-harvested. Too many people were eating too many oysters. When the oyster beds around Staten Island became depleted in 1820, the status of oysters around New York took a turn for the worse. Undeterred by this harbinger of things to come, New York continued to harvest oysters at an even greater pace. By the early 1900s, over 1 billion oysters a year were being pulled out of the area’s waterways.

Another major threat to the oyster beds was the city’s ever-expanding shoreline. Between 1609 and 2010, Manhattan grew by roughly 20%. What was once a shoreline of marshy, rocky shallows — an ideal environment for oyster beds — had been replaced with a nearly unbroken string of bulkheads, piers, and landfill. It was good for trade and commerce, but bad for marine biodiversity.

Lastly, waste management, or the lack thereof, contributed to the oyster’s demise. Until circa the 1970s, New York was dumping millions of gallons of raw, untreated sewage into the harbor on a daily basis. (Today, the city’s combined sewer system still ejects sewage with stormwater during peak flow). Not surprisingly, the oyster beds could not survive. Due to fears of food-borne illness, including typhoid, the New York City Health Department closed the Jamaica Bay oyster beds in 1921, which were responsible for 80 million oysters a year. From there, oyster bed closures spread across the city quickly: six years later, in 1927, the last New York City oyster bed was closed in Raritan Bay.

With the passage of the Clean Water Act fifty years later in 1972, the harbor was given minor respite, but it was too little and too late. New York City oysters would survive as a species, but they would not be fit to eat again any time soon. And just like that, New York City had squandered one of its greatest natural resources, by imposing upon their habitat, over-harvesting their population, and dumping sewage on all that remained.

It’s said that oysters are a perfect real-time reflection of their surroundings. So it follows that if the people living near oyster beds are reckless and poisonous to their environment, then it will show in the oysters. Oysters were some of the first victims of gentrification in New York City (the first of course being, tragically, the Lenape people).

Today, New York would do well to make amends with the oyster, given all the oyster can do for New York. For one, oysters clean the waters in which they live. They are tiny beasts of burden in this way, designed to withstand troubled water and capable of filtering up to 50 gallons of it per oyster, per day. Oysters also act as keystone species, attracting other marine life to live around them, from microscopic organisms to crabs and fish.

Of course, there is also the legend of their aphrodisiac powers. According to a 2005 New York Times article, oysters are high in zinc, and a zinc deficiency has been shown to lead to sexual impotence. So, sure, maybe there’s a link. Though scientifically speaking, there is no such thing as an aphrodisiac, so probably not.

Still, there is something vaguely romantic about eating oysters. They are an occasion, and eating them requires a certain amount of ceremony. Furthermore, few things could elicit one’s mortality — and one’s joy for being alive — more than eating a living thing: the raw oyster. From the violent cracking open of their shell to the risk of foodborne illness, eating oysters, like love, can be messy, expensive, and potentially harmful to one’s well-being. So, even if eating these tasty bivalves doesn’t lead to romance, it certainly can resemble it.

In New York specifically, oysters were once unsung local heroes — yet they promise to play a role in its success once more. Figuratively, New York City was made with oysters insofar as they provided a cheap and abundant food source and generations of employment. But even literally, a fair amount of New York City is made with oysters, most notably the lime used in Trinity Church is comprised of ground-up oyster shells. Nearby, Pearl Street is named for the piles of oysters left there by the Lenape.

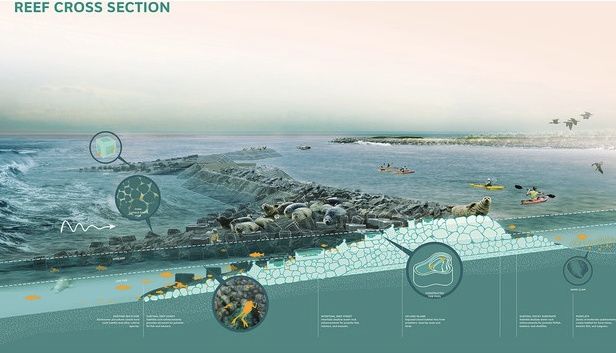

In Tottenville, Staten Island, a different kind of oyster structure is under construction. SCAPE/Landscape Architecture has introduced Living Breakwaters, a series of oyster walls reinforced with concrete just past Staten Island’s southern shore, an area particularly beat up during Hurricane Sandy. This 13,000-foot reef which began construction in 2021 has already started to attract marine life. It also serves to clean the surrounding water and, most importantly, protect against future storm surges. Gina Wirth of SCAPE/Landscape Architecture told DNAinfo in a 2014 interview that the oyster walls would “reduce water velocity, reduce erosion of the shoreline, and reduce the height and intensity of waves.” Tottenville, once known as “the town oysters built,” is now wagering that oysters are its best shot at survival.

Tottenville is just one area where oysters are staging a comeback around New York City. Leading this revival is Billion Oyster Project. As the name suggests, Billion Oyster Project hopes to restore one billion oysters to New York Harbor. They began in 2012, and so far have returned around 122 million live oysters to the harbor, primarily around Governor’s Island and at the mouth of the Bronx River.

Affiliated with the New York Harbor School, Billion Oyster Project educates New York City teenagers on maritime vocations and ecology by way of oyster restoration. To do this, Billion Oyster Project collects oyster shells from restaurants around New York City, such as Grand Central Oyster Bar and Gramercy Tavern, to help seed the new oyster beds. Oyster spats, aka baby oysters, float around oyster beds until they find a good surface to call home, and an old oyster shell from a fancy New York restaurant will do just fine. The students tend to the spat and recycled shells at floating cages that serve as breeding grounds for the oysters before they are returned to the harbor.

Sam Janis of Billion Oyster Project says they are going to need trillions of oysters to get the job done, not just a billion. ”In some ways, New York Harbor is unrestorable,” says Janis. “I mean, not restorable by our own hand. Nature has its own course. But I don’t think it’s fair to say the oyster is going to save the harbor.”

However, the benefits of breeding oysters and better sewage disposal practices have already changed the course of New York Harbor: “Compared to 50 years ago there is a lot of life in the harbor. Many magnitudes more biodiversity and bioproductivity,” says Janis. “No longer dumping millions of gallons of raw sewage into the harbor every day can do that.”

In 2018, workers restoring a pile at the southeast corner of Pier 40 noticed an unusually large oyster. After turning it over to The River Project, they learned it was the largest oyster found in the Hudson River in over a century. It is rare to find an oyster in New York’s waters that has survived long enough, an estimated ten to fifteen years, to get to that size. It measured almost nine inches long, about the size of a women’s size seven shoe. Though not the largest on record, this big find is evidence of the oyster population making its comeback.

Even though it remains a long shot, the oysters are down there below the surface working tirelessly for the benefit of New York Harbor. They are greatly outnumbered, sure, yet still determined to leave the water a lot cleaner than they found it, and certainly a lot cleaner than we left it.

Next, uncover mythical sewer alligators: fact or fiction? Author Tom Hynes writes a series on Untapped New York about the quirky history of NYC’s wildlife.

Editor’s Note: originally published in 2016, updated August 2024

Subscribe to our newsletter