Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

The following article about New York during the horse era is being published posthumously. It was written circa 1952 by Lewis A. Coffin, who was a New York-based architect with Polhemus & Coffin until his death in 1963. Among many other New York City projects, he designed 232 Madison Avenue, the Geer Memorial Gateway at Barnard College, and the Columbia University Boathouse. His grandson Barclay T. Leib recently unearthed the following manuscript from Mr. Coffin’s papers.

I’ll likely be long dead before anyone ever reads these memories, but I have left these notes amidst my family papers. Perhaps some eagle-eyed grandson or granddaughter of mine will someday find them to be of interest.

My memories are of New York around 1899 — when I was just a boy of seven.

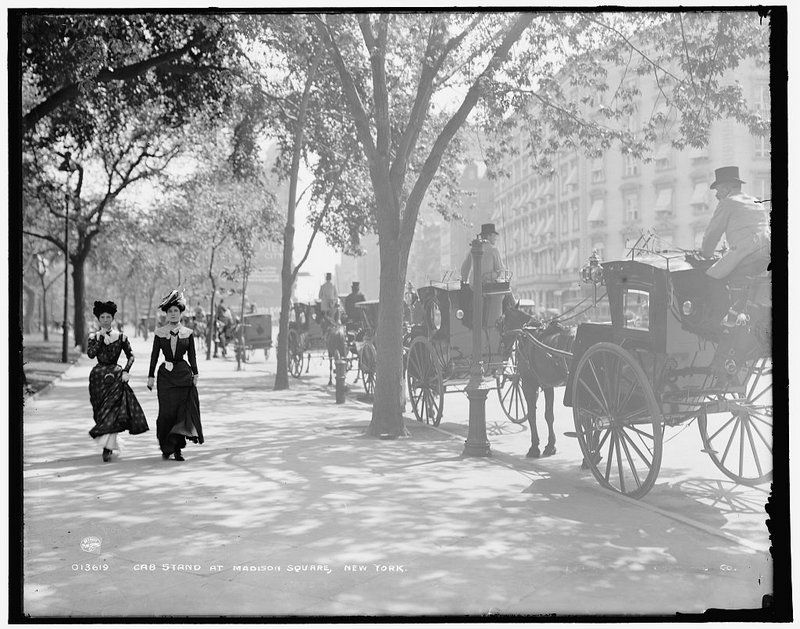

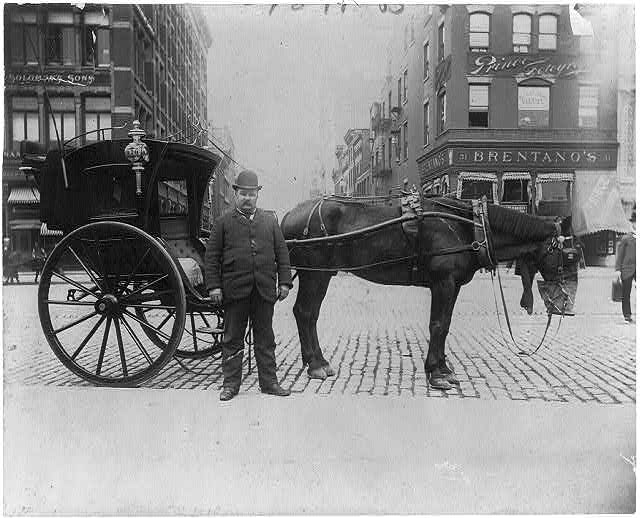

It was a New York before brakes screamed and horns honked. There were no car engine motors. It was a New York filled with a great many horses, carriage and harness shops, horse markets, stables, and street cleaners with scoops. It was a New York still filled with bustles, bonnets, and brownstones.

Our family in those days lived on Twelfth Street. On Sundays it was our custom to go to church way down at St. Paul’s Chapel on Vesey Street where my Reverend Uncle was the Pastor. This was a lengthy ride on the Sixth Avenue-West-Broadway horse cars. As a little boy I rode kneeling on the seat, looking out the horse car windows at the passing “fin de siècle,” while the driver urged on the bobbing horses, or turned the brass brake handle round and round to brake the car.

In the winter the little stove with a pipe through the roof threw out a pleasant warmth, while the horses clawed uncertainly at the slippery cobbles. Overhead steam locomotives — which seemed like giant toys to me — whirled the elevated trains downtown at dizzying speed. My family preferred the horse cars. They thought they were safer.

In those days my father, practicing medicine, kept a horse, and I went with him a great deal on his calls. He loved a good horse and always had one, but I have never gotten over the impression that a good horse can still be a trigger-brained animal. I used to have to hold the horse’s head while my father made his visits. The task irked me. It was better to roller skate or climb back-yard fences with my friends. The task bothered me too because the horse was sometimes too high strung and would start restlessly — often swishing his tail at flies. If the horse was nervous, I was more so. If the horse became really disturbed, my state of mind grew even more panicky.

One day the horse cuffed at a fly and came down on my sneakered foot. He did not notice it. I did. I remonstrated, but the horse paid no attention and leaned comfortably on the offending hoof. I pushed him, but he thought I was joking. The whole experience helped to turn me into an onlooker where horses were concerned.

It may be that another event had more to do with that. We used to roller skate on the uneven flag sidewalks until the cobbles in our street were taken up and the smooth asphalt rolled down. While the workmen were at it, we had a lovely time, with the steam roller clanking up and down, and many splendid barrels of tar. A piece of tar, properly warm, can be chewed, modelled, strung out into rope, compacted, and finally thrown. Parents, I remember, disliked tar.

At any rate, after the asphalt was laid, we used to roller skate in the street, hitching up and down the block on all possible carriages and wagons that passed. One day I swung off a fast express wagon, about to perform a rolling telemark to the curb, when I found myself under the wheels of a cart laden high with chickens in coops. I remember the driver scrambled to his feet, cursing. I had been generally run over. It spoilt my lingering faith in horse-flesh. I was down and the horse kicked me.

In the winter time there were many pitiable sights in the streets of horses trying to draw their loads when the pavements were like glass with ice or snow. The horses would fall in great numbers. Then they lay quiet, open-eyed, puzzling, until pulled up by the bit and lashed at by the barking drivers. The horses would then scramble up, steel hoofs dashing sparks. If, falling again the horse broke a leg, a policeman would draw his gun. On old Murray Hill there has certainly been frightful carnage.

Sometimes my father traded in his horse or bought a new one. Then I went with him to the Market which used to be near the Winter Garden, I believe where Roseland is now, at 52nd Street and Broadway. In the tan bark ring, horses were trotted around. A bell rang intermittently. The Auctioneer called the prices and pounded his gavel. He had black drooping mustaches, and of him I was really frightened. My father was friendly with the owners, and while he circulated, I used to sit in the stuffy little room laden with the finest horse and harness smells, looking at the pictures of hunters and steeplechasers, and wishing that I was instead playing follow-the-leader on the front stoops.

Those were the exciting days of run-a-ways; of shouting and scrambling as some horse — gone beserk — careened his cart crazily down the avenue, and of heroic pursuits and one-handed stops by New York’s Finest. Nowadays, we will get the occasional crash of a car, but not the same lovely suspense of a horse chase.

Back then, fine carriages drove forth, black gleaming, with two men on the box with shining toppers, quite as grand as any long-nosed limousine. And there were no service stations, gas stations, hot dog signs, no fast food “Eata-Bites” stands, or bad air.

The family went driving sometimes for pleasure. My father’s horse was smart, and with a new yellow buckboard, we felt proud driving up Seventh Avenue and through the Park. My father always carried his whip and kept the horse stepping up. One day we went as far as the Speedway which was just opened then. I remember the smart racing gigs and those two-wheeled carts, licking their way up the Speedway at a rapid clip. Coming down through the Park and Fifth Avenue there were myriads of cabs, victorias, handsomes, and the Old Fifth Avenue Coaches — everything being drawn by horses. It is obvious to say so, but somehow it seems so strange — not being that many years ago.

Out of the dingier side streets came the sound of hammer and anvil, loud and insistent. When we went to have our horse reshod, I watched the smithy beat out the flaming iron and pump the bellows, and I remember well the hiss and smell of the burning hoof which floated out into the street.

Any little boy gets excited when the first snow comes. I often leapt out of a warm bed to the window in the grey light of a winter morning, hearing the ringing scrape, scrape, scrape of the street cleaner’s scoop. And turned back to bed shaken in spirit. No snow, only the morning clean up.

Yet when a good snow did come it was with the muffled sound of the horses’ hooves and far-off tinkle of sleigh bells. Sleighs appeared in great numbers, sliding smoothly up the Avenue for a brisk turn in the Park, while the bells danced on the horses’ shoulders. There was something good about that Old New York winter time — a muting of all sounds in the snowy street, all but the ambitious shovel on the sidewalk, and the bells singing a steady song along the avenues.

No little description of the Horse Era in the city could be complete without a respectful mention of the spine-tingling thrill of the old horse-drawn fire engine and hook-and-ladder teams. Oh, but to hear the far-off scream of the steam siren, the ringing of the mad bell on the scarlet engine up the avenue, and to see the horses spread out in speed under the lash of the whip. The driver in his red helmet would lean far forward as he reigned the steeds safely through the traffic at furious speed. Those were men of fire, and so too, those wonderful horses, and no boy of that era will ever forget them.

Sounds at night are important too, and how different they used to be. No longer does one lie in bed thinking of this and that in the silence of the night, and hear the old clippity-clop, clippity-clop of the late cab, nor is one bestirred in the morning by the trot, trot of the milkman. Oh! I know there were horses on milk wagons until recently. But I hear the sound of horses no more — save on those horse-drawn wagons which still parade plants and flowers in the spring.

How New York has changed from the Horse Era – which now only lives in my memories.

Next, read about the Gilded Age Fifth Avenue Mansions of Millionaires Row!

Subscribe to our newsletter