Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

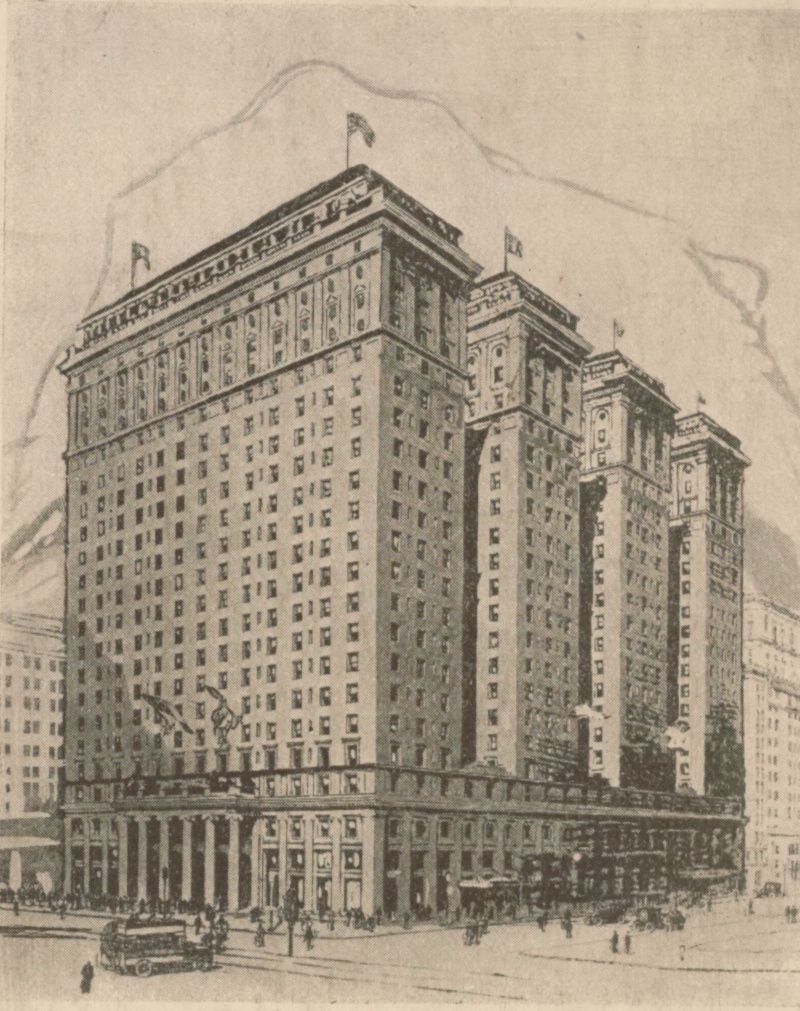

The Hotel Pennsylvania is quietly disappearing and will soon be gone forever. Despite efforts to preserve the historic building, and previous hopeful announcements of renovation, demolition of the Hotel Pennsylvania is now more than halfway complete. Interior demolition began in 2022. Designed by the illustrious firm of McKim, Mead, and White as a companion to the original Penn Station, the hotel opened in 1919 on Seventh Avenue between 32nd and 33rd Streets. Here, we uncover the secrets of the Hotel Pennsylvania, soon to be another New York City building relegated to the history books:

When the Hotel Pennsylvania closed permanently in April 2020, it was the fourth largest hotel in New York City, a pretty impressive stat. But when it opened on January 25th, 1919, it was the largest hotel in the world. Rising 22 stories, the hotel boasted 2,200 rooms, each which its own private bath as an ad in the Chicago Tribune noted. It cost $10 million to build. A crowd of 3,000 visitors flocked to the hotel on opening day.

The second-largest hotel was also a New York City building, according to the New York Times. The Hotel Commodore near Grand Central Terminal had 200 fewer rooms. Hotel Pennsylvania was surpassed in size by the New Yorker Hotel in 1930. The New Yorker soared 43 stories and had over 2,500 rooms.

The two elderly hecklers featured sitting in the balcony of many Muppets shows and movies are named Statler and Waldorf after two famous New York City hotels, The Statler and The Waldrof-Astoria. The Statler was one of a handful of names Hotel Pennsylvania has gone by in its 100+ year history. When the hotel first opened it was run by Ellsworth M. Statler of the Statler Hotels chain. It was later purchased by Statler in 1948 and renamed. The chain had locations across the country in cities like Detroit, Saint Louis, and Buffalo.

Hotel Pennsylvania has also been named The Statler Hilton, New York Statler, and New York Penta, as its ownership changed hands. The curmudgeonly Muppet characters made their first appearance in 1975. Statler is the character with darker grey hair, a long face, and a cleft chin. He was originally played by Richard Hunt.

In 1921, Hotel Pennsylvania established its very own newspaper, the only hotel to do so at that point. The paper was called The Pennsylvania Register. In a newspaper interview in 1921 with the paper’s editor, Mrs. Grace Crawley Oakley, the reporter describes the contents of the 4-page journal: “interviews with distinguished guests, news of what is going on in the hotel and in the city, what to see at the theater, interesting excursions about town, special varieties of service offered by the hotel, a page devoted to prominent guests in the house and various other news of interest including a humorous column, whose title. Pen Points, was contributed by a hotel employee.”

The paper was delivered to every room every day except for Sundays and holidays. It was left in the servidor, a unique attraction of Hotel Pennsylvania that set it apart from other hotels. Servidors, now often called valet doors, were cabinets near the hotel room doors that could be opened from both inside the room and from the hallway outside. Guests could leave shoes to be shined and clothes to be pressed inside and they would be inconspicuously picked up by hotel workers on the other side. Other deliveries could be left there as well without disturbing the guests.

Hotel Pennsylvania’s phone number was allegedly the oldest continuing phone number in New York City. That number was Pennsylvania 6-5000. Even after names and letter codes became obsolete, the number maintained the numerical version of PE 6-500. This number has been immortalized in a song by The Glenn Miller Orchestra. The orchestra, and other famous acts of the time such as Duke Ellington and Count Basie, often played at the hotel’s Café Rouge.

“Pennsylvania 6-5000” became more than just a number in 1940 when a song of the same name was released by RCA Victor. The music was written by Jerry Gray with lyrics by Carl Sigman and it was performed by Glen Miller and his band. The song, which is a swinging big band tune, became a hit and advertised the band’s performances at the hotel. Later, the song was used as background music for the hotel’s phone answering machine for many years.

In September 1935, a furry creature caused quite a stir in the hotel lobby. On a Saturday night, a monkey bounded into the lobby of the Hotel Pennsylvania. “Through the entrance the monkey scurried, bouncing along the gleaming corridor rimming the hotel’s telephone booths,” The New York Times reported. As two nearby taxi drivers chased after it, “the monkey leaped from table to lamp and showed no interest whatever in being captured.”

Eventually, the creature was caught and driven to a police station. One of the drivers surmised that the monkey had come from Frank Buck’s jungle camp in Massapequa, Long Island, while others thought it might have been one of the escaped monkeys from the Willard Parker Hospital where the animals were used for medical experiments and drug tests. Four escapees were on the loose at the time.

On November 28th, 1953, Frank Olson died after a fall from the window of room 1018a at the Hotel Pennsylvania, then the Hotel Statler. Olson worked as a bacteriologist for the Department of Defense. His death was initially deemed a suicide, but later reports would tie the incident to the CIA’s top secret mind control project MK-Ultra and illicit an apology from President Gerald Ford himself

Olson worked for the Special Operations Division of the Army’s Biological Laboratory at Fort Detrick and was part of the MK-Ultra project, a research operation started in the 1950s. Nine days before his death, Olson attended a Special Operations conference with other members of the CIA at Deep Creek Lake in Garrett County. There, CIA chemist Sidney Gottlieb and his deputy Robert Lashbrook served attendees drinks laced with LSD. The subjects were drugged without consent.

When Olson returned home from the conference, he was changed. He attempted to resign from his position at the CIA. In response to this request, the CIA sent Olson to New York with Gottlieb and Lashbrook to seek care from a doctor with experience in the effects of LSD. The doctor recommended that Olson be sent home for psychiatric treatment. That night, Olson called his wife to say he would be coming back. The next morning was the fateful fall.

Olson’s family was told that the fall was an accident or an intentional jump, but didn’t mention that Olson had been the unwitting participant in a drug experiment. That part of the story came out in 1975 when the Church Committee report released findings from an investigation into the practices of the CIA. That is when Olson’s family received an invitation to the White House where President Ford offered an apology in the oval office. The family also received a $750,000 settlement. Still, Olson’s sons weren’t satisfied with the narrative they were given by the CIA. Frank’s son Eric alleges that his father was murdered. The mysterious case is the subject of the 2017 Netflix documentary series, Wormwood, directed by award-winning filmmaker Errol Morris and starring Peter Sarsgaard, and the book A Terrible Mistake: The Murder of Frank Olson and the CIA’s Secret Cold War Experiments written by Olson’s nephew.

The Hotel Pennsylvania hosted countless conventions throughout its 100+ year run. One of the most influential was the International Convention of Comic Art which started in 1968. Before the organized convention, comic book fans met informally. George R.R. Martin says he got the first ticket to New York City’s first Comic Con, which took place in 1964 in Greenwich Village with around fifty people. The convention at the Statler-Hilton was born out of comic book fan meetings organized by Phil Seuling, an English teacher at Brooklyn’s Lafayette High School.

The inaugural event included guests of honor like Stan Lee and Burne Hogarth. The annual convention took place over Independence Day weekend from 1968 through 1983. The International Convention of Comic Art was the first and largest convention of its type until the 1980s. By that time, fandoms and comic book companies in other cities had begun to organize and San Diego’s Comic-Con soon became the dominant convention.

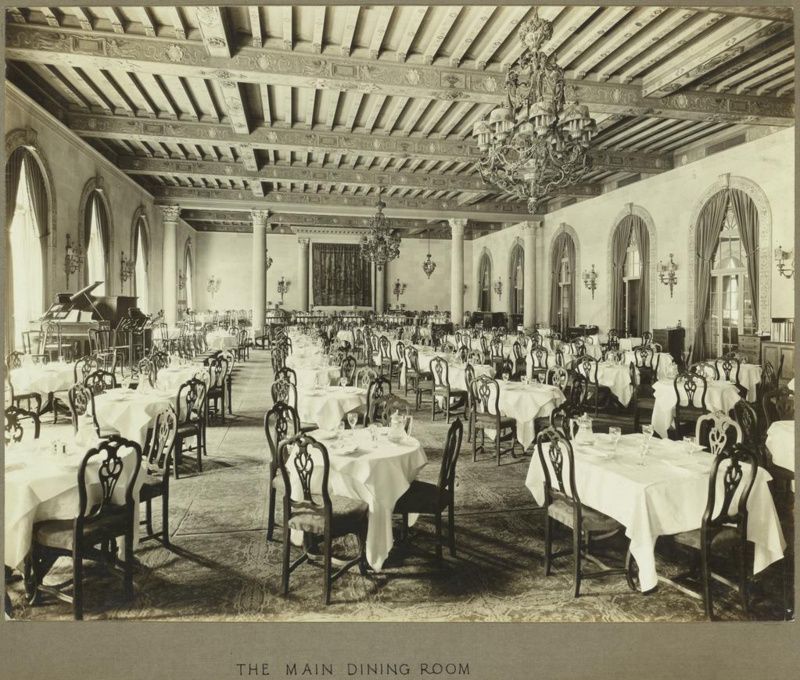

Café Rouge was the hotel’s main restaurant. It was a large room with 22-foot ceilings and three main sections, a central floor with two raised terraces on either side. In an issue of The Architectural Review, the dining area is described as having “a distinctly Italian character, with wall base, and door trim of terra cotta, artificial limestone walls and a beamed ceiling which has been carefully studied in color to increase the apparent height of the room and has been treated to give the effect of the old wooden beamed ceilings.” Large arched windows ran along the exterior wall.

The Café had its Golden Age during the 1930s and 1940s when big bands performed for crowds of diners. After a major renovation in the 1980s, the café was one of the few areas of the hotel that still boasted its original architectural features. The former dining space was converted into an events venue that operated separately from the hotel. In 2014, Café Rouge became Terminal 23, an indoor basketball court created to promote the launch of the Melo M10 sneakers by Nike. Despite the conversion and white paint, you could still the beamed ceiling and remnants of the floor-to-ceiling fountain before the Hotel Pennsylvania demolition began. An immersive show called ZeroSpace was the latest installation to occupy the space.

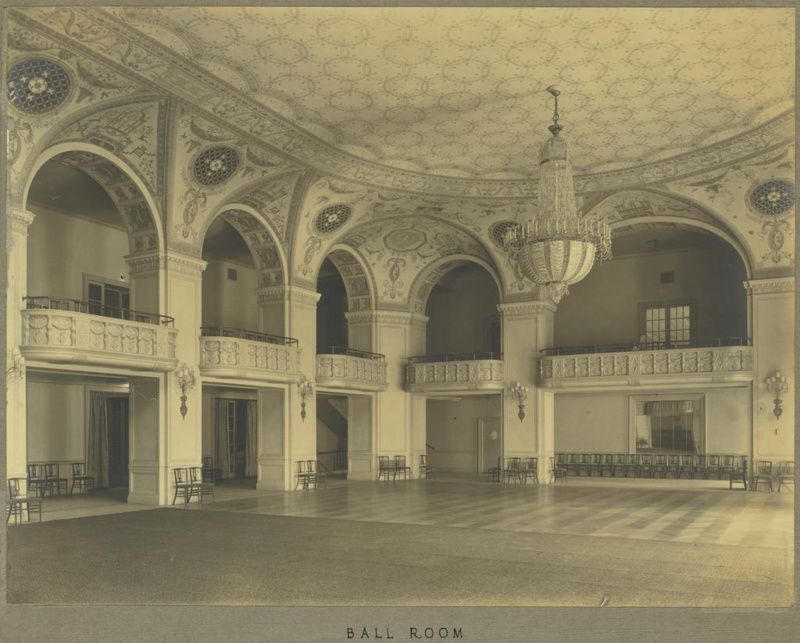

In 1995, the hotel’s grand ballroom was converted into a television studio. The space was leased by Image Group, which spent $6 million on construction and equipment. The room’s 30-foot high ceilings and lack of support columns made it ideal for building out a studio.

Shows such as The People’s Court, Maury, and Sally Jessy Raphael were shot there throughout the 1990s and early 2000s. In 2009, the studio was condensed to 10,000 square feet and converted for a short-lived sitcom called Sherri starting Sherri Sheperd.

Joaquin Maria Argamasilla was known as “the man with X-ray vision.” Hailing from Spain, the illusionist claimed he could see through objects. He demonstrated his powers by reading notes locked in boxes and telling the time from clock faces that were covered.

Houdini debunked Argamasilla’s act on multiple occasions. The first time he saw Argamasilla’s act was at the Hotel Pennsylvania in 1924. After Argamasilla performed his act, Houdini stepped up and made a bet that he could replicate all of the supposedly paranormal feats the performer completed. Argamasilla and his manager were insulted and left the hotel while Houdini attempted to replicate the act. Largely due to Houdini’s incessant denial of his powers, Argamasilla faded from the public eye.

Next, check out 10 of NYC’s Lost Grand Hotels

Subscribe to our newsletter