A Salvaged Banksy Mural is Now on View in NYC

This unique Banksy mural goes up for auction on May 21st in NYC!

Image in public domain from Wikimedia Commons

These are grim times for New York political bosses. Former Speaker Sheldon Silver’s corruption trial ends on Monday. Former Senate Majority Leader Dean Skelos’ corruption trial has just begun. Former Kings County Democratic Chairman Vito Lopez is dead.

Today is an anniversary celebrating a rare win for New York reformers: on November 19, 1871, William “Boss” Magear Tweed was arrested. Here are some fun and surprising stories you may not have known about the infamously corrupt Boss Tweed:

Who doesn’t like firefighters? Until 1865, New York’s firefighters were all volunteers, which had its problems – often drunk, they struggled to actually put out fires. But firefighters were still loved in the community, and Tweed, who exhibited a charismatic touch, was recruited by Tammany to run for Alderman (today’s City Council). He quickly was elected to Congress, but utterly bored, he returned home after one term to take a series of party machine posts like Deputy Street Commissioner. The streets of New York were paved with patronage gold.

The history of the city’s firefighters is well-documented at the New York City Fire Museum on Spring Street.

The Draft Riots of 1863 are regarded as the deadliest racially incensed insurrection in American history, aside from the Civil War. Image from Library of Congress

The Civil War Draft Riots of June 1863 marked one of the ugliest chapter in the history of New York City. Working-class Irish who resented the laws that allowed wealthier men to circumvent the upcoming drafts for a war they perceived to be purely about another racial group took to the streets, setting fires, demolishing property, lynching people, and battling with the police. Tweed not only supported the Union war effort, but he knew violence was bad for business. He and his Tammany allies sought to quell the riots, even saving the mayor from an angry mob.

Tweed’s solution to the Draft Riots was classic Tweed. He proposed that the city secure a bond to pay the $300 exemption fee for anyone who would rather not fight, as well as the bounty fee for whoever took their place. This extraordinarily expensive remedy kept the peace, but also nearly bankrupted the city.

Now all New Yorkers supported the Union however. You can read about Benjamin Morris Whitlock who built an opulent mansion on the Bronx that is now lost.

Image in public domain from Wikimedia Commons

Many people casually conflate Tammany Hall with the Tweed Era. While Tammany was a force on the New York political scene for more than a century, Tweed’s prime was only about five years. Tweed was elected State Senate in 1867. He was also named Tammany Hall “Grand Sachem” in 1869 and appointed to his favorite patronage mill, the Department of Public Works in 1870. For a brief moment, Tweed was the king of New York, the master of all things political and financial in the Empire State. (The city’s debt tripled in two years.) But by summer of 1871 it all came crashing down.

The Union Square East view of the former Tammany Hall headquarters, which now serves as the campus for the New York Film Academy and houses the Union Square Theater.

Yes, the Tammany machine depended on the reliable votes of new immigrants, but as Terry Golway writes in Machine Made: Tammany Hall and the Creation of Modern American Politics “Earning and keeping the Irish vote was more than simply a matter of naturalizing immigrants and sending them on they way into the alien streets of New York, it required constant attention.” (Incidentally, Tweed was of Scottish descent.)

While Irish recruitment had begun before Tweed’s tenure as Grand Sachem, Tweed poured unprecedented amounts of taxpayer money into schools, hospitals, poor houses and local infrastructure. Did he do so efficiently or fairly? Of course not! However, later Tammany alums like Al Smith later took the early welfare models and executed them at the state level, creating a safety net and economic rights for all New Yorkers, not just Tammany voters.

You can still see a remnant of the Tammany era too – the New York Film Academy Building in Union Square was formerly the Tammany Society.

The Tweed Courthouse is considered the ultimate boondoggle in the history of New York public works. Taking nearly two decades, with cost overruns in the millions (real money back then), the construction generated infamous bills, like more than $41,000 for “brooms” The New York City government now houses the Department of Education in the Tweed Courthouse.

The building is one of the city’s landmarked interiors and contains a Roy Lichtenstein sculpture in its 5-story atrium.

The E 17th Street facade of the former Tammany Hall headquarters, where its political past shares the space with signs for its present day theatrical tenants.

You know those annoying upstate legislators always meddling in New York City affairs? Turns out it has always been thus. Tweed’s whole purpose for taking over state government was so that he could transfer power back to the city, making it easier to manage. But upstate legislators wouldn’t give up their power so easily, as attached as they were to the bribes they received from downstate special interests. Tweed came out on top with an amendment that restored some self-governance to New York City. The new City Charter was good for Tammany business, but it was also supported by leading reformers like Peter Cooper (of said Village).

We’re not talking about just landing a contract for a buddy, or sneaking an appropriation into the budget. Depending on your metric, $200 million in 1871 is worth many billions of dollars in today’s money, and it was used to line the pockets of Tweed’s Ring. Other members of the ring include “Elegant” Abraham Oaks Hall, a dapper prototype for future Tammany Mayor “Gentleman” Jimmy Walker (he also served as counsel to Mayor Fernando Wood, infamous for his motion that Manhattan should secede from the Union). Hall ran into problems when his mishandling of a religious parade led to a Irish Catholic v. Irish Protestant brawl that killed 62 people. The brains of the operation was Parks Commissioner Peter Sweeney, whose schemes are reminscent of Office Space‘s Michael Bolton. The Comptroller was “Slippery Dick” Connolly. Enough said.

These four men trusted each other little, and the Ring’s self-destruction was a question of if, not when. When the relatively young New York Times began invesitgating this story in the summer of 1871, Tammany was only mildly threatened – at one point they tried to buy out the paper to kill the story. But publisher George Jones would not sell, and the shocking revelations of theft, lies and greed led to a full investigation.

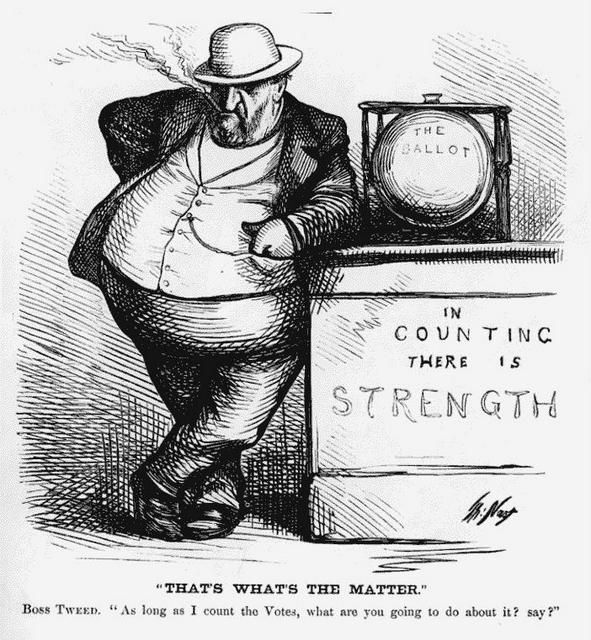

Alfred Ely Beach’s pneumatic tube subway in NYC that ran on Broadway between Warren and Murray Streets. Photo in public domain from Wikimedia Commons.

Alfred Ely Beach’s pneumatic tube subway in NYC that ran on Broadway between Warren and Murray Streets. Photo in public domain from Wikimedia Commons.

A precursor to the subway, the Tweed operation supported the construction of underground pathways that used steam power to transport horse carriages as fast as 50 mph. When Tweed and his Ring went down, the project was considered corrupt by association. In a desperate effort to re-brand the project, its supporters argued that Tweed had been the one to hold it back. It was all for naught, as the Panic of 1873 wiped out financial markets across the country and dried up investment in the tubes. New York City would have to wait three decades for a subway, as Tweed shut down competitor Alfred Ely Beach’s pneumatic tube subway that ran on Broadway between Warren and Murray Streets

Pneumatic tubes did come into favor to transport smaller items – evidenced in the well-developed mail delivery system under New York City and is present in other institutional and corporate locations.

Inside the Samuel Tilden House in Gramercy Park, now The National Arts Club

Known as the politician who brought down Boss Tweed, New York Governor Samuel J. Tilden was an aristocratic politician who had no compunction about working with Tweed while he was in power. But following the Times’ revelations, he formed the Committee of Seventy, which included a who’s who of old money New Yorkers. On November 19, 1871, Tweed was arrested, and Tilden was soon elected governor. Always remember, today’s reformer is tomorrow’s clubhouse man. (Or woman!)

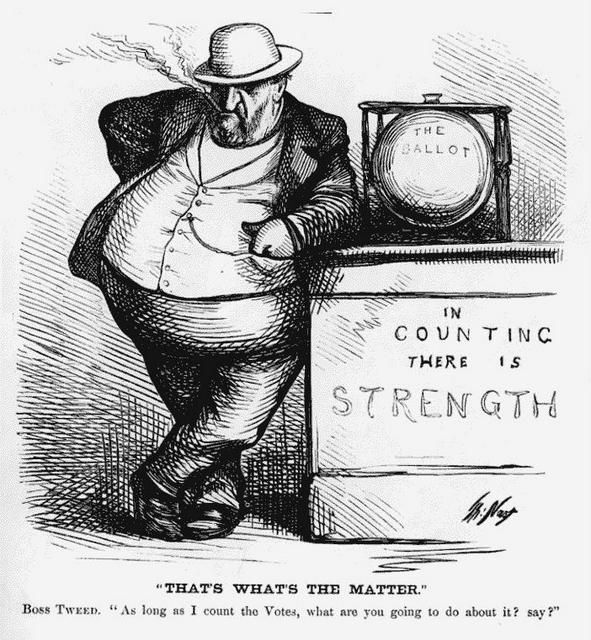

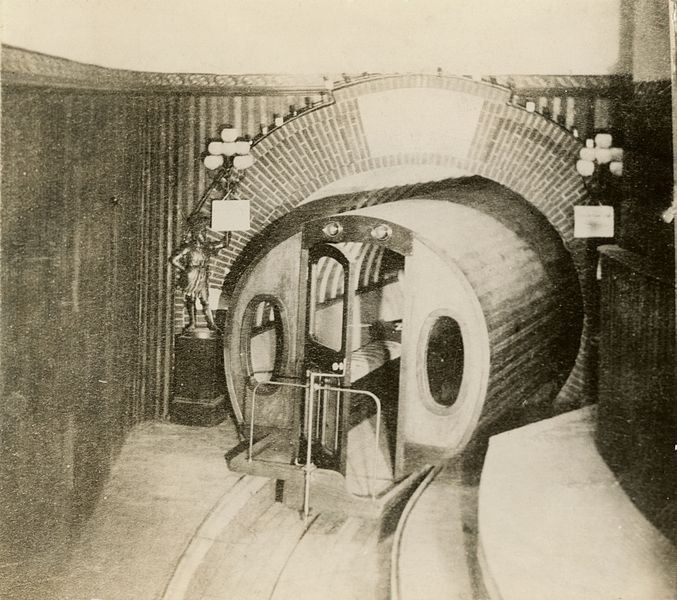

Thomas Nast caricature of Boss Tweed in Harper’s Weekly, October 21, 1871. Image in public domain from Wikimedia Commons

Thomas Nast, basically the godfather of political cartoons, took an extreme disliking to Tweed, mocking his girth and love of money in a series of devastating cartoons. Tweed, who famously brushed of criticism from his political opponents (“What are you going to do about it?” was his mantra), lamented, “I don’t care a straw for your newspaper articles; my constituents don’t know how to read, but they can’t help seeing them damned pictures.”

After his conviction in 1873, Tweed was still permitted the occasional home visit. During one visit, he escaped out the back of his house and escaped across the ocean on a Spanish boat, posing as a fat, old sailor. At the Spanish border he was recognized by Floridian tourists on vacation, who’d seen his mug in a Nast cartoon. The authorities brought him back to New York, where he died in prison.

Tweed always believed other pols were just as crooked. While in prison, he received word that his sentence might be lifted in exchange for a confession, which led to a full revelation of his crimes. Unfortunately, Tilden and his associates would not honor that agreement.

Beyond the cartoons, Tweed also lives on in the Bad Book of Bill: Rogues, Rascals and Rapscallions Named William, Bill and Willie, by Lawrence Binda.

In case you were wondering whether New Yorkers were just duped dopes during the Tweed Era, keep in mind that it was the beginning of industrialization, and the City was doing very well. As historian Kenneth Ackerman puts it in Boss Tweed: The Corrupt Pol Who Conceived the Soul of Modern New York “It seemed like a great free ride, especially for the banks and brokerage houses making huge commissions on the bond sales. Tweed economics — borrow, spend and keep some for yourself — made sense to New Yorkers. Even the poor benefited.”

Next, check out the Top 10 Secrets of NYC’s City Hall building, just back to back with the Tweed Courthouse.

Subscribe to our newsletter