Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

In 1918, 102 years before the rise of the coronavirus, the “Spanish Flu” pandemic began to kill millions of people worldwide. The flu infected 500 million people around the world, 27% of the world’s population, and killed anywhere from 17 million to 50 million people. In the first year of the pandemic, the average life expectancy in the United States had already dropped by 12 years.

The source of the Spanish Flu virus is not as easily traceable as the coronavirus. Hypotheses suggest that Spanish Flu began in northern China, a UK army base in Étaples, France, and in Haskell County, Kansas. The disease was first observed in January 1918, but by March 1918 the virus had already hit Queens. The virus occurred in three waves, the first in early 1918, the second and most deadly in late 1918 into early 1919, and the third during the middle of 1919.

New York reported its first death from the virus on September 15, 1918. After all three waves of Spanish Flu, about 33,000 New Yorkers out of a population of 5.6 million died, 21,000 of whom died during the second wave.

A traffic cop wearing mask in New York City in October 1918. Photo from National Archives.

It was anticipated at the beginning of the flu that New York would be hit hard by the virus. The most diverse and populated city in the United States at the time, New York grew exponentially during recent waves of immigration that sent Eastern and Southern European families into tiny tenements with little to no running water or electricity. With many of New York’s best doctors overseas during World War I and with many immigrant families maintaining a distrust of modern medicine, New York appeared to have an extremely high flu rate. Additionally, New York also served as the departure and arrival point for over a million troops heading to the battlefields in France.

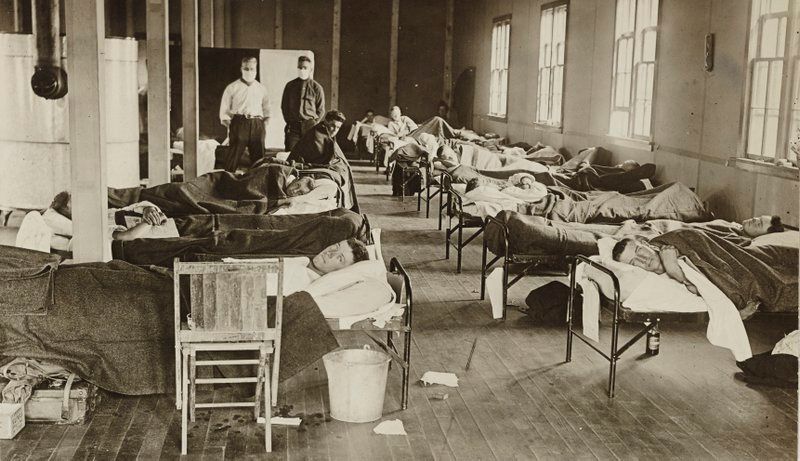

Flu cases at a barracks hospital in Colorado in 1918. Photo from National Archives.

Medically, the disease was very different from coronavirus, killing people in their 20s, 30s, and 40s, with little opportunity to test and self-quarantine, as the New York Times reports, noting importantly that the world had not even seen what a virus looked like. Protective equipment for health care workers was virtually non existent.

Yet, during the pandemic, New York City’s excess death rate was a rather low 4.7 per 1000 people, compared to 6.5 in Boston and 7.3 in Philadelphia. For such a vulnerable city, New York City took a very proactive approach in controlling the pandemic through strong public health infrastructure and rather revolutionary tactics to control death rates.

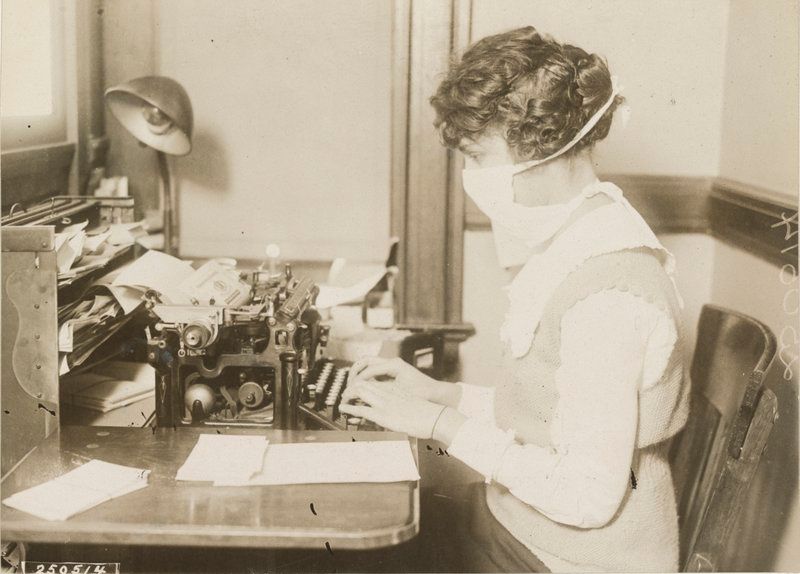

A typist wearing a flu mask in New York City in October 1918. Photo from National Archives.

Newly appointed President of the New York City Board of Health Royal S. Copeland attempted to prevent the spread of the disease despite a few grave errors early on. Prior to late September 1918, reporting the flu was not mandated, and although testing was possible, according to the New York Times, “it was impossible to test people with mild symptoms so they could self quarantine.” Despite growing concerns and increased death rates in New York, “it was nearly impossible to do contact tracing because the flu seemed to infect — and panic — entire cities and communities all at once.” By the end of September, New York had already reported around 50 deaths, yet health authorities were slow to act since they believed the rate of infection would soon after decline and did not want to send the public into disarray by taking dramatic precautions. Additionally, health authorities failed to realize that asymptomatic carriers could also spread the disease without experiencing any symptoms. The existence of asymptomatic carriers of disease had been widespread knowledge in New York since Typhoid Mary in the early 1900s — an immigrant cook who was eventually banished to North Brother Island to prevent her from spreading typhoid.

The Board of Health on October 4 created a very effective timetable to regulate the opening and closing hours of businesses. The timetable staggered the hours of when businesses were open to ease congestion in public transit systems especially during rush hours. As opposed to ordering all businesses to be closed, Copeland argued that the virus had a low incidence and was fairly concentrated. The timetables were often changed to accommodate the needs of businesses including department stores and theaters.

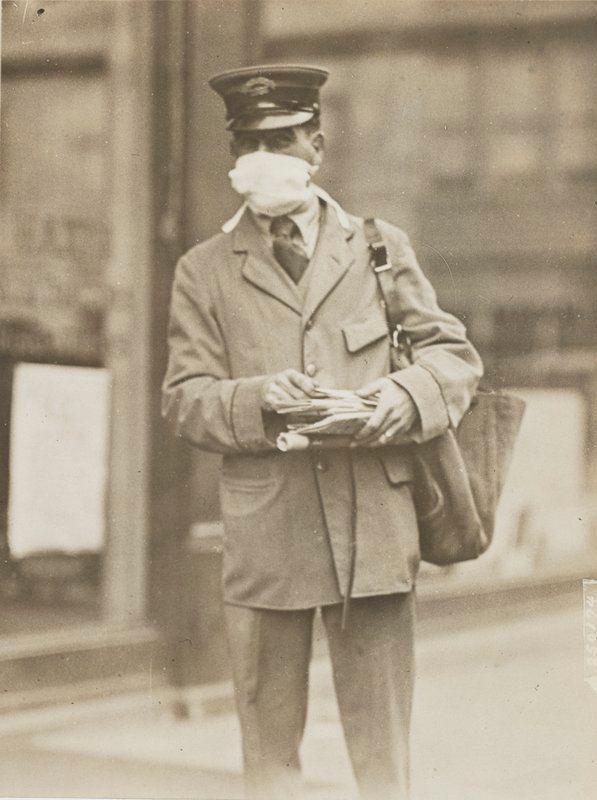

Letter carrier wearing mask in October 1918. Photo from National Archives.

Letter carrier wearing mask in October 1918. Photo from National Archives.

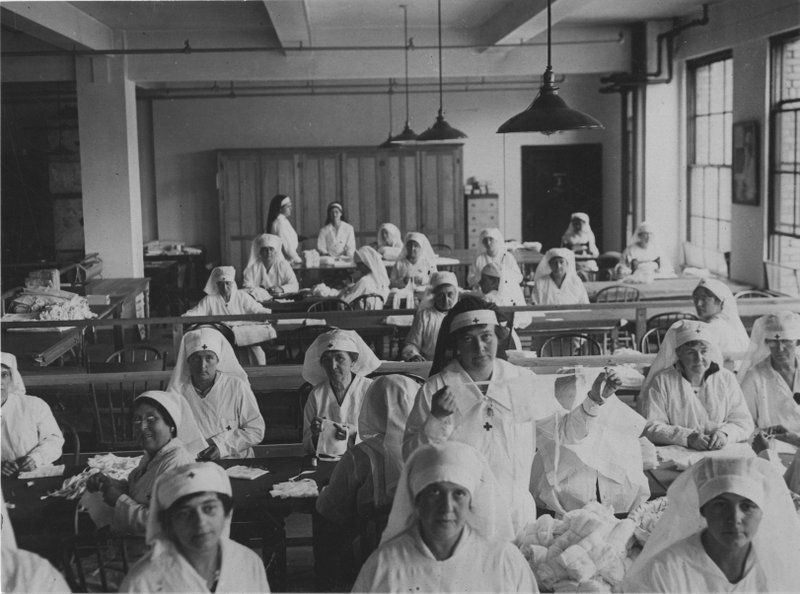

Copeland also rolled out a “clearinghouse plan” on October 7 that divided New York City into sub-units and established 150 temporary health centers. Many of these centers served as headquarters for nurses delivering home health care in these new districts as well as clinics that kept track of available hospital beds. In a letter to New York City Mayor John Hylan, Copeland wrote, “We have districted the city so that every neighborhood has its agency for the protection of that immediate territory. Through this centre we will supply nurses, domestic help, food and medicine.”

By October 19, the structure of the Department of Health changed significantly, with more authority granted to each borough’s sanitary superintendents. Borough heads had increased power to “remove, abate, suspend, alter or otherwise improve” establishments that sold or stored food.

Making gauze masks at Red Cross Headquarters in October 1918. Photo from National Archives.

Copeland also decided to keep schools open, arguing that children are better protected in schools where they are constantly under supervision than on the streets. Especially for poorer children living in unsanitary conditions, schools provided these children an escape from unhygienic environments and allowed children to be more informed about the progression and spread of the disease. Copeland also felt that teachers and school health officials could identify early symptoms and could direct children towards treatment options. In schools, leaflets were established and bulletins were put up about how to prevent the spread of the disease, which contributed to New York’s low infection rate.

In terms of quarantining sick individuals, travel restrictions and port closures were common, and some ill patients were forcibly isolated on North Brother Island or in other state-run facilities in New York Harbor. In addition, people were sometimes kept at home for the duration of their illness with a placard indicated their sickness placed on their door. Since many doctors and sanitarians could not rigorously enforce isolation orders, self-isolation was the best practice for keeping the disease from spreading. About 10,000 posters with quarantine instructions and guidelines on how to best protect others from the disease were displayed around railway stations, store windows, and other public spaces.

During this time, theaters including Broadway were kept open and were regularly inspected. Although theaters were spaces where disease could be spread to hundreds of people, the Department of Health noted that theaters could educate the public about how not to transmit the flu and could prevent the spread of hysteria. Many theaters prohibited children younger than age 12 from entering movies or shows.

We can already see some parallels and divergences with how New York City and State are handling the coronavirus pandemic. Schools have been closed and movie theaters, restaurants, and other non-essential indoor places where people gather have been ordered to close, but the reasoning for keeping those spots open in 1918 are not as applicable either. There is still however, concern about homeless school children who require New York City schools for essential services. We no longer have quarantine islands and hospitals and we have not yet set up a network of government run health centers since it is likely more efficient to activate private clinics and hospitals to test and treat. We will start to see the opening of more mobile testing facilities however, the first was opened in New Rochelle this past Friday, and two more are slated to open on Staten Island and on Long Island. Get the latest news on coronavirus in the New York City region in our daily digest.

Next, check out NYC’s former quarantine islands and hospitals.

Subscribe to our newsletter