Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

Everything’s pricier in Manhattan, including air. For the deteriorating Pier 40 on the Hudson River, air may just be the key to survival–at a heavy price. Much needed funding for the Hudson River Park piers could come from a recently passed state bill that allows sale of the piers’ air rights (the empty, developable space above a property) one block inland. It’s an unprecedented debate over the ability to transfer air rights of a temporary structure like a pier. With this bill comes concerns about the impact of further development of these inland properties.

Hudson River Park, a five-mile-long strip of greenery along the Hudson River, has struggled for long-term funding in the past few years. One of the primary culprits behind the park’s upkeep costs is Pier 40. Last year, the pier’s falling roof and general deterioration racked up an estimated $125 million price tag. As a solution, a number of redevelopment plans have been proposed for the pier, including a parking garage, a theater and a shopping complex. But part of the hindrance comes from the original legislation permitting construction of the Hudson River Park that limits Pier 40 to commercial and retail use–no condos or schools, for instance. The legislation passed in June would allow the Hudson River Park Trust to sell the pier’s air rights to lots up to one block east. In a market where the desire to develop upward is in high demand, these sales could easily fund the pier’s hefty repairs.

But how do air rights work, and how can they be “transferred”? Air rights became legal to sell in 1961, when the new zoning ordinance set quotas on the allowed density of square footage on each block, as well as height and setback limits. Moreover, the sale of air rights to fund preservation isn’t new. Grand Central Station funded its construction in this manner, resulting in the transformation of Midtown East into a business district highly populated with high-rise buildings. Whereas properties can typically sell their air rights only to sites that share a border of at least ten feet, registered landmarks such as Grand Central can sell them to lots across or down the street. The new legislation seems to loosely apply this allowance to Pier 40.

Other features of the bill that have not received as much public attention include an expansion of the allowable commercial uses at Pier 40 that allows developers to construct schools, amusement park rides, performance spaces and film studios. The pier will also be able to charge fees for passengers on tour boats that dock there. Beyond Pier 40, the bill also permits the city to relocate its tow pound on Pier 76 so the space can be converted to a park. All these changes are geared toward the ultimate goal of Hudson River Park’s self-sustainability.

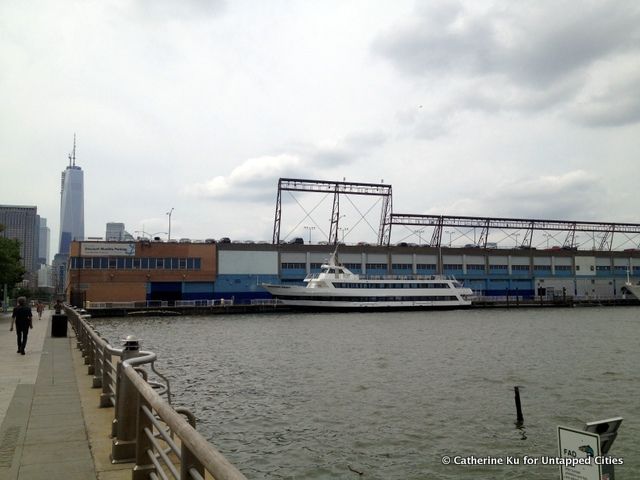

Looking east from Pier 40, the skyline is composed of mainly low-rise buildings (unlike skyscraper-dominated Midtown).

While the sale of air rights beat out the other proposed plans, its effects won’t be limited to the pier itself. Some issues raised in an editorial in The Villager by Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation director Andrew Berman include how a temporary structure like a pier can have salable air rights–and whether these rights would still exist if the pier were destroyed in the event of a hurricane. Berman writes:

But perhaps most disturbingly, this new mechanism creates a strong incentive for our current zoning to be reopened to not only allow the transfer of air rights from the piers — which would allow larger development inland to fund the park — but to go beyond that and allow even greater development in our neighborhoods as part of the deal.

Just a block inland, there’s already 100,000 to 250,000 square feet of available air space for development, as Chelsea, SoHo and the West Village have traditionally been low-rise neighborhoods. In the event of an air rights sale, the city must rezone the area of proposed development for construction to begin. Though it will take time for development plans in these neighborhoods to be debated and developed, if they’re approved, the city’s skyline could look very different along the Hudson River in a few years.

Get in touch with the author @catku.

Subscribe to our newsletter