How to See the Liberty Bell...in Queens

A copy of the famous American bell can be found inside a bank, which itself is modeled after Independence Hall!

Map maker John Tauranac shares his expert insight on mapping New York City's complex underground transit system!

How do you best represent the complex New York City subway system on an easy-to-read map? That's a challenge John Tauranac has been working on since the 1970s, when he chaired the MTA's subway map committee. Tauranac served as the creative director of the official New York City Subway Map published in 1979, guiding the shift from Massimo Vignelli’s abstract schematic design to the more geographic based maps we use today. Untapped New York sat down with Tauranac to discuss his approach to mapmaking and how his latest subway map conveys crucial information in innovative ways.

January 29th at 6 PM ET: Free to Untapped New York Members at the Fan tier or higher.

Tauranac is a lifelong New Yorker, writer, historian, and professor who came to mapmaking through exploring and writing about New York City. "My father imbued a specific appreciation of the city in me as a kid," he told Untapped New York, "The idea of living in any other major urban place was beyond his perspective, he loved the city." A love Tauranac carries on.

Through his father's work managing hotels, including The Biltmore Hotel—a lost hotel once connected to Grand Central Terminal— Tauranac was introduced to Manhattan's underground pedestrian tunnels. "I came to understand those undercover passages of Grand Central from my father and then I realized there's a tremendous complex under Rockefeller Center, and linking Penn Station there was another," Tauranac said.

To share this fascinating information, he created his first maps. "Undercover Maps," which illustrated subterranean walkways connecting buildings in Midtown and Lower Manhattan, were published in New York Magazine in 1972 and 1973.

He began his work with the MTA by writing guidebooks for the MTA's Culture Bus Loops I and II, published in 1974 and 1975. He also wrote Seeing New York: The Official MTA Travel Guide in 1976.

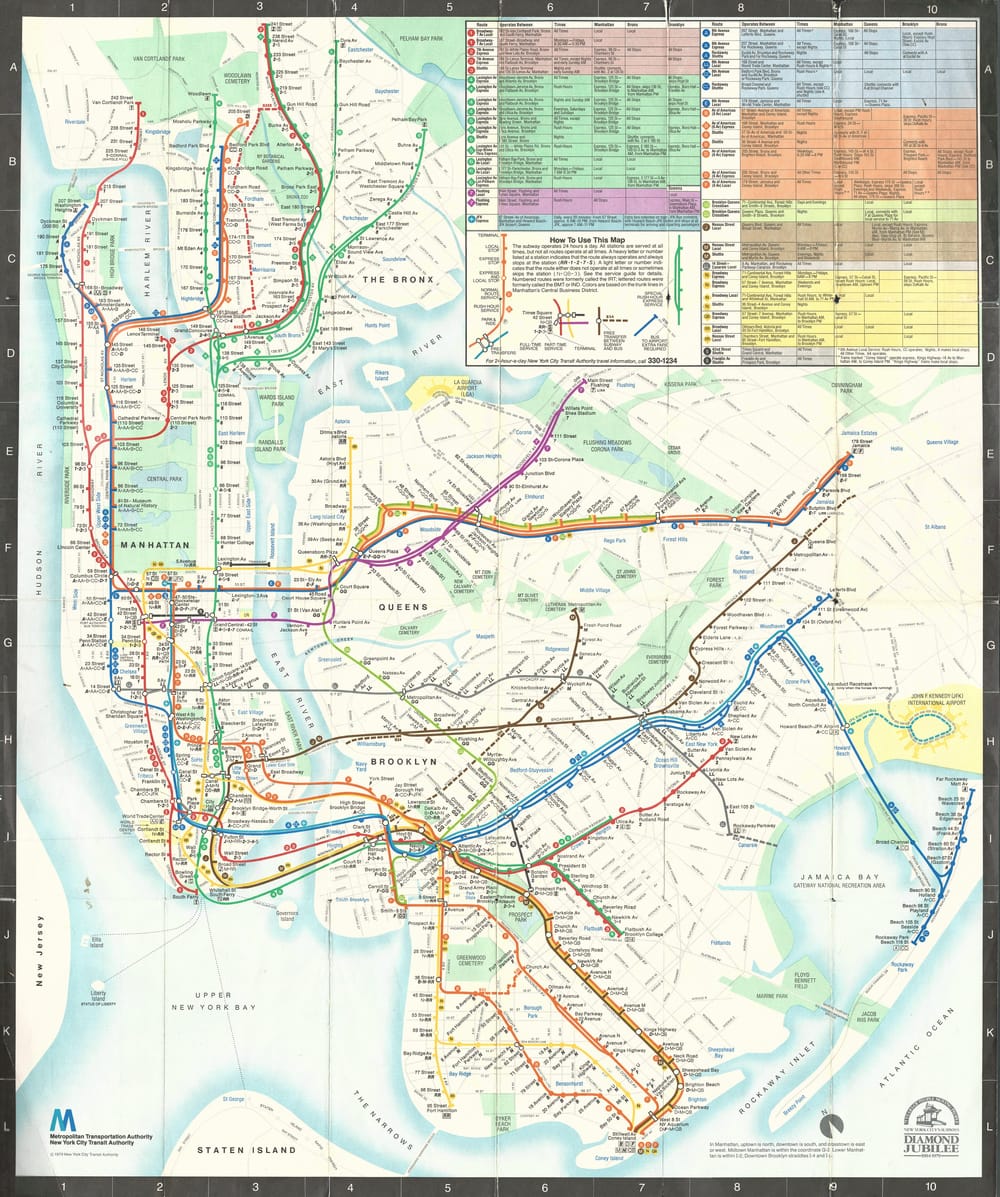

Massimo Vignelli's 1972 map of the subway was the official map at the time. While this schematic representation of the system was lauded by designers, it wasn't as loved by subway commuters. The map did a fine job of showing how to get from one subway station to another, but it was difficult to relate each station's location to the streets and landmarks above.

Tauranac believed a geographic map would solve this problem. "The MTA agreed there should be a new perspective on mapping the subway," he said, so the transit authority created a new map committee with Tauranac in charge.

Tauranac had a completely different approach to mapping the system than Vignelli. The two mapmakers took part in what has been billed as "The Great Subway Map Debate" at the Great Hall of Cooper Union in April 1978, where each defended their position.

"One of the things I said as I was flashing a piece of the Vignelli map on the screen—and I realized it was an unpleasant thing to say," Tauranac recalled, "I said, 'I know what New York City looks like, and it doesn't look like this.' But that's really the key to the difference between a quasi-geographic map and a schematic map, or a diagram as Vignelli liked to call it."

Tauranac collaborated with a team at the design firm of Michael Hertz Associates, including sculptor and painter Nobuyuki "Nobu" Siraisi, to make a geographic map. The result was the official MTA subway map of 1979, a map that showed the subway system with a simplified trunk-based color scheme over a quasi-geographic representation of the city's landmasses, bodies of water, and parks.

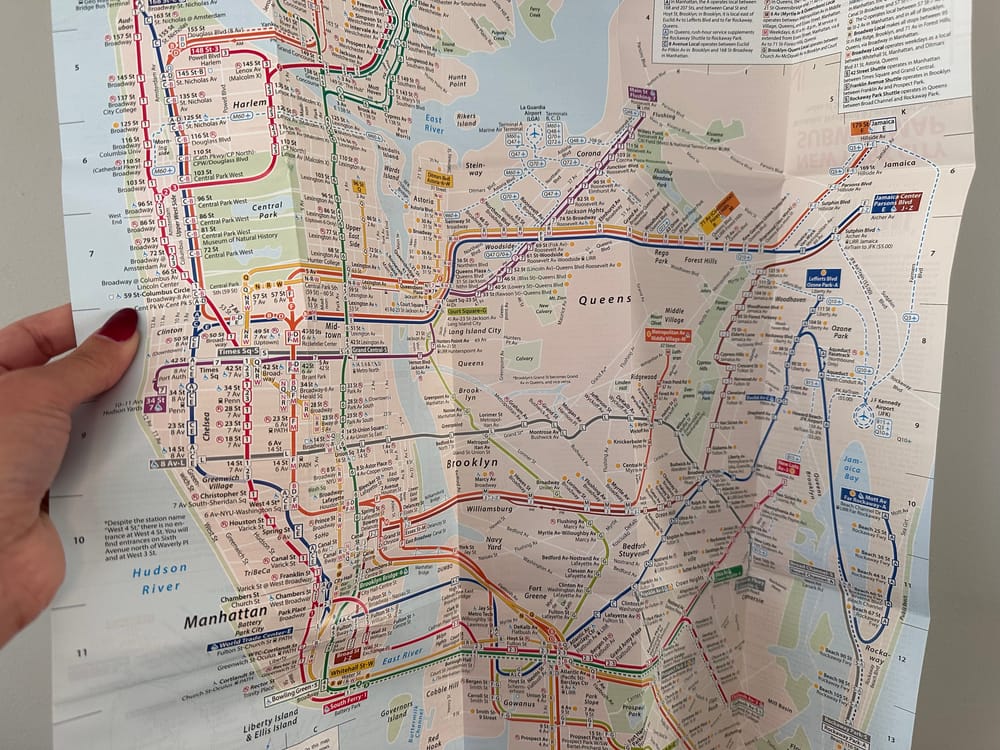

After his work with the MTA, Tauranac continued to create maps for various institutions and publications such as Historic Battery Park, both the Grand Central and Lincoln Square Business Improvement Districts, and multiple editions of Kenneth T. Jackson’s Encyclopedia of New York City (Yale University Press). He has also continued to perfect his own version of the New York City subway map. He released his latest map in 2020.

The 2020 map shows weekday, weekend, and late-night service. "There are many part time services. There's service that operates weekdays only, service that operates weekends only, service that stops at a station during rush hours, service that does not stop at a station rush hours," Tauranac points out. To simplify this information he came up with another color-coded system.

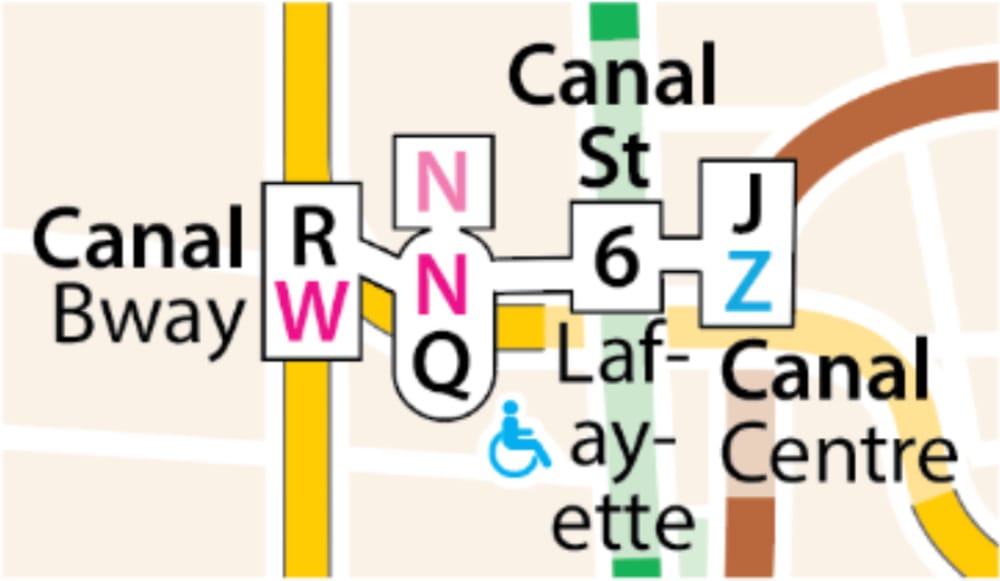

"If I show a number or letter in black, it means it operates at that station seven days a week, if it's red it means 'Watch it!,' it only operates weekdays. Pink is another 'watch it' that only operates weekends, blue for rush hour service, and so on. The colors impart all the critical information that you need," Tauranac explains.

There are a variety of features like this that differentiate Tauranac's map from the typical subway map. For example, local and express service are noted right on the route lines with the service encased by a square or rectangle for local and a circle or oval for express. These are typically framed in the color of the trunk line, but as in the example below, if there is a transfer, the outline is a neutral black.

"I also include as an integral part of the station name the street of operation," Tauranac notes. "If you just see a train stops at 79th Street and the name of the street of operation is somewhere running along side the route, you have to look at two places in order to learn the coordinates. By incorporating the street of operation as an integral part of the station name you answer the immediate question of 'Where is this place?'"

As for the biggest challenge when it comes to mapping the subway, it's making sure New York City looks like New York City. "This is a quasi-geographic map, not truly geographic," Tauranac said, "so there are areas such as Midtown that are expanded. When you're making something like a schematic map or a diagrammatic map, it don't make no nevermind if you've got five subway lines running along side each other, you just fatten everything, widen everything. If there's nothing much happening you contract the space, it doesn't matter. When you're making a quasi geographic map, you try to keep things in perspective. That's what makes it's difficult."

You can pick up a copy of Tauranac's map from Barnes and Noble locations in Manhattan including stores at 2289 Broadway, 1550 Third Avenue, 555 Fifth Avenue, and 33 East 17th St and in Brooklyn at 267 Seventh Ave, and 194 Atlantic Avenue. You can also order online from Landmark West.

Besides making maps, Tauranac has published multiple nonfiction books about New York City. His latest release, New York’s Scoundrels, Scalawags, and Scrappers: The City in the Last Decade of the Gilded Age, is set for publication in Spring 2025.

January 29th at 6 PM ET: Free to Untapped New York Members at the Fan tier or higher.

This post contains affiliate links, which means Untapped New York earns a commission. There is no extra cost to you and the commissions earned help support our mission of independent journalism!

Subscribe to our newsletter