Celebrate St. Patrick’s Day in NYC 2025

Discover 10 ways to celebrate St. Patrick's Day in NYC this year, from eye-opening tours to Irish treats!

Jazz music originated in New Orleans during the early 1900s, with African-American musicians creating the music style to celebrate their heritage while still striving to fit into the wider American music scene. As the 20th century progressed, the country’s youth began to crave more exciting music and jazz rose to fill in this desire. By 1917, due to a variety of factors including the Spanish flu pandemic, New Orleans jazz musicians began to leave for Chicago. However, jazz music’s popularity in Chicago declined during the 1920s, and musicians migrated again, this time to New York City. After the election of Jimmy Walker as mayor in 1926, speakeasies—establishments known for encouraging free discussions and the sale of bootleg alcohol—were made legal, coming to serve as the perfect breeding ground for the rise of jazz. Learn more about the overlap of jazz culture and speakeasies across New York City, and listen to original recordings from iconic jazz clubs of NYC, on our “Legendary Jazz Clubs of New York City” virtual tour which can be viewed in the Untapped New York Insiders on-demand video archive.

As jazz took hold of the New York City music scene, clubs arose throughout the city to satisfy the growing demand for one-of-a-kind performances. From the Cotton Club – which hosted Duke Ellington’s Orchestra – to the Apollo Theater, which helped start the career of Ella Fitzgerald, these jazz clubs transformed New York City into a haven for jazz musicians. Read on to learn more about the legacy of some of the most famous jazz clubs in NYC, both past and present!

The Cotton Club first opened its doors in 1920, known then as the Club Deluxe, under the leadership of heavyweight boxing champion Jack Johnson, who rented the upper floor of a building on the corner of 142nd Street and Lenox Avenue in the heart of Harlem. Bootlegger and gangster Owney Madden took over in 1923, changing its name to the Cotton Club. Soon after, Johnson and Madden entered into a partnership together in which Johnson remained the club’s manager while Madden was free to use the space as a venue for selling alcohol illegally during the Prohibition Era. Though the Cotton Club only operated for two decades, it came to serve as a cultural hotbed, grooming some of the era’s greatest jazz musicians including Duke Ellington, Dorothy Dandridge, Cab Calloway, and Louis Armstrong. At the same time, the Cotton Club remained a whites-only establishment—with rare exceptions made only for Black celebrities such as Ethel Waters or Bill Robinson.

Reflecting the socially accepted racist ideologies of the time, images of Black people hailing from exotic jungles or as slaves working in the Deep South on plantations were visible throughout the establishment. One prime example of this could be viewed in a 1938 menu which displayed illustrations of naked Black men and women dancing around a drum in the jungle. Poet and social activist Langston Hughes famously critiqued the Cotton Club after visiting the establishment, calling it a “Jim Crow club for gangsters and monied whites.”

Every year, the Cotton Club would host two musical revues, which consisted of dance, singing, and comedy acts displayed for the chance of eventually becoming a successful Broadway show. These musical revues would go on to help jumpstart the careers of many artists such as Andy Preer who led the club’s first house band in 1923. From 1927 to 1931, the Cotton Club’s house band switched to Duke Ellington’s Orchestra and in June 1935, the club’s doors were finally opened to Black patrons. After the 1936 Harlem Race Riots, the Cotton Club temporarily closed but reopened later that same year at a new location on Broadway and 48th Street. Bill “Bojangles” Robinson and Calloway would go on to lead the club’s most extravagant revue on September 24, 1936—featuring 130 performers. Robinson’s participation ended up costing the club $3,500 a week, the highest salary ever paid to a Black entertainer in a Broadway production.

Eventually, amid rising rent prices and a federal investigation into tax evasion by numerous Manhattan nightclub owners, the Cotton Club was shut down permanently in 1940. The Latin Quarter nightclub soon took its place, focusing on hip hop, reggaeton, and salsa music with similar vibes that matched its fiercest competitor, the Copacabana. Since its closing, the Cotton Club has been heavily featured throughout American pop culture, with examples including the music video for “Oye Como Va” by Cuban-American singer Celia Cruz, Francis Ford Coppola’s 1984 film The Cotton Club, and a 2013 episode of White Collar entitled “Empire City.”

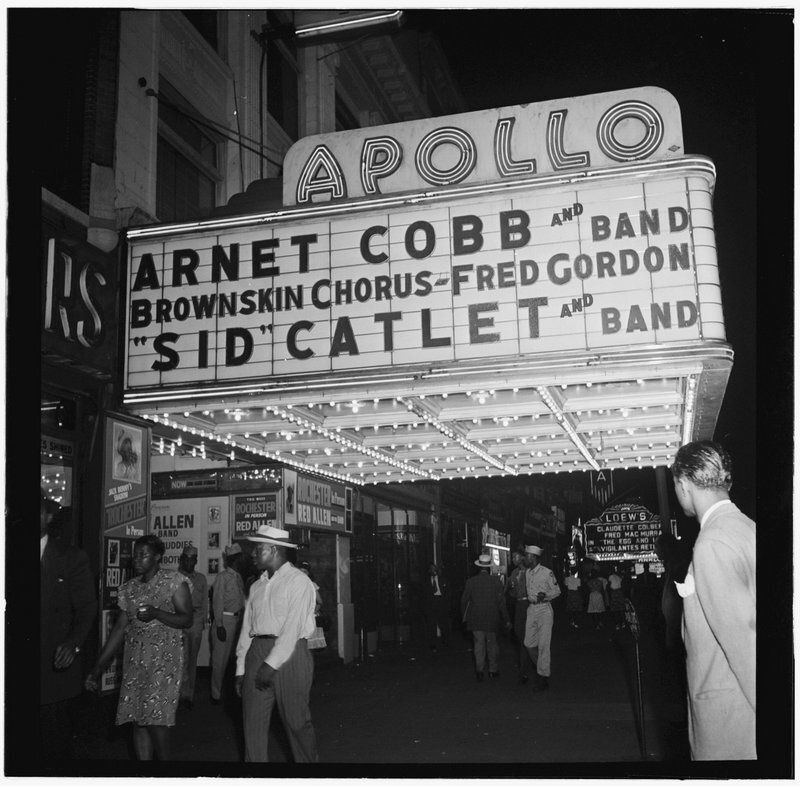

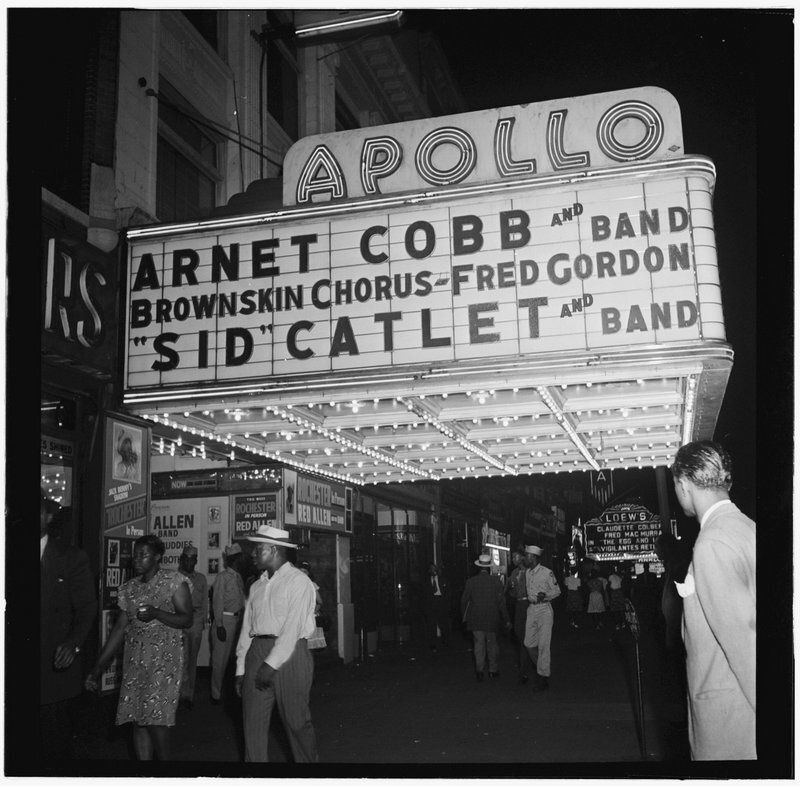

The Apollo Theater’s neo-classical building—located at 253 West 125th Street—was designed and built by architect George Keister in 1913. A few months later in 1914, noted burlesque producers Jules Hurtig and Harry Seamon obtained a 30-year lease for the property, giving it the name Hurtig and Seamon’s New (Burlesque) Theater and operating it as a whites-only establishment with a capacity of 1,506 people. In 1924, the Minsky brothers gained ownership of the theater and began to lease the space for burlesque shows, some of which included integrated casts with Black performers. After Fiorella La Guardia, one of New York City’s future mayors, began a campaign against burlesque in 1933, the theater was purchased by Sidney Cohen. Lavish renovations to the space soon followed and it was renamed the 125th Street Apollo Theater—to avoid confusion with the Apollo on 42nd Street. The theater also began to shift towards showcasing variety revues and catering to Harlem’s growing African-American community, becoming a prime venue for its performers to shine.

By 1937 the Apollo Theater had become the largest employer of Black theatrical workers in the United States. Typical shows at the Apollo bore many similarities to vaudeville, having a chorus line of girls—though these became less common as time passed. Over the years, the theater has remained at the forefront of the American music scene—having played a major role in the emergence and rise to prominence of jazz, swing, bebop, R&B, gospel, blues, and soul music. Countless performances from many of the time’s most prominent Black musicians took place at the Apollo including Billie Holiday, Adelaide Hall, and Sammy Davis Jr. In addition, the Apollo Theater became known for hosting Amateur Night contests beginning in 1934. At just 17 years old, a young Ella Fitzgerald became one of the contest’s first winners on November 1, 1934, after singing Hoagy Carmichael’s “Judy” and “The Object of My Affection” by the Boswell Sisters. Over the years it has become a tradition for contestants to rub the Apollo’s “tree of hope” for good luck before their performances. Though the stump currently resides in the theater’s wings, it was originally taken in the early 1930s from a tall elm tree on 7th Avenue—known informally during the early 20th century as “the Boulevard of Dreams” as it housed the city’s black theater district. Currently, tap dancer Howard “Sandman” Sims holds a record for having won the Amateur Night competition 25 times. After finishing his reign as the contest’s champion, Sims moved on to become its executioner—using a broom to sweep performers off the stage at the behest of the audience—a role he played from the 1950s to 2000.

Though the Apollo Theater had some of its most successful years during the 1960s—even starting to host its own drag show entitled “Jewel Box Revue”—rising drug problems in Harlem, a series of robberies and theft, and the shooting of the 18-year old Darrel Sculliark eventually led to its closing in 1976. On April 1 and 2, 1976, Fred and Felicidad Dukes along with Rafee Kamal produced two 60-minute television specials to help restore life to the theater.

The Apollo briefly reopened in 1978 under new leadership only to close again in November 1979. After being purchased by the private investor group Petty Sutton, the theater was revitalized and equipped with its own recording and television studio. 1983 saw the building gain state and city landmark status and in 1991, the non-profit Apollo Theater Foundation Inc. was founded to help manage and oversee the theater’s programming. To this day, the Apollo Theater continues to live up to its storied legacy, bringing striking performances to the public, providing educational opportunities in the arts for elementary, high school, and college students, and continuing to give nascent performers the opportunity to showcase their talents on the stage.

The Savoy Ballroom began operation on March 12, 1926, as one of the country’s first racially integrated public venues. The Ballroom evolved under the vision of owner Moe Gale – a Jewish businessman – and manager Charles Buchanan, an African-American businessman, and civic leader. Buchanan and Gale envisioned for the Savoy to serve as an alternative for individuals interested in dining in a more refined atmosphere than the time period’s typical nightclubs offered. Located at 596 Lenox Avenue—considered to be the main thoroughfare through upper Harlem—the Savoy Ballroom was coined by poet Langston Hughes as the “Heartbeat of Harlem” in “Juke Box Love Song.” The ballroom’s name was taken from the Savoy Hotel in London to give it a more classy and upscale feeling.

Due in part to the ballroom’s non-discrimination policy, it ended up serving a clientele of around 85% Black and 15% white, though there was sometimes an even split. During the ballroom’s peak years, which lasted from the 1920s to the 1940s, the Savoy generated around $250,000 in annual profit from an entrance fee ranging from 30 to 85 cents depending on the time of day, rising in price later in the evening. Measuring in at 10,000 square feet with a capacity of 4,000 people, the Savoy Ballroom was modeled after the Roseland Ballroom, providing passionate Black dancers a venue to display their talent. The ballroom came to host many of the best dancers of Lindy Hop, an American dance style created in the African-American community of Harlem. Named after Charles Lindenburg, the Lindy Hop or Jitterbug rose to prominence during the swing era of the late 1930s and early 1940s, giving the ballroom the nickname downtown as the “Home of Happy Feet” while uptown in Harlem it was known as “The Track” for its long and thin flooring. Other well-known dances conceived at the Savoy include the Flying Charleston, Jive, Snakehips, Rhumboogie, and iterations of the Shimmy and Mambo.

With a double bandstand that held one medium and one large-sized band, music was continuously played in the Savoy. During the 1930s, jazz musician Chick Webb served as the bandleader for the Savoy’s most popular house band, being joined by a young Ella Fitzgerald who served as its teenage vocalist. Besides Webb, other prominent bandleaders for the Savoy included Al Cooper, Lucky Millinder, and Buddy Johnson. In October 1958, the Savoy Ballroom went out of business, despite efforts by Borough President Hulan Jack, Buchanan, and other organizations to save it. One of the most cherished Jazz clubs in NYC, it is widely regarded as a tragedy for the entertainment world that it was demolished in Spring 1959 for the construction of the Delano Village housing complex. To honor the ballroom’s legacy, a commemorative plaque was built on Lenox Avenue where the Savoy once stood on May 26, 2002. Nineteen years later on the anniversary of the plaque’s installation, a Google Doodle rhythm game was created featuring popular swing dance tunes.

Known today as one of the oldest remaining jazz clubs in NYC, the Village Vanguard was first opened by Max Gordon at Charles Street and Greenwich Avenue in 1934. However, due to an insufficient area of facilities, Gordon was unable to procure a cabaret license which impeded his plan to operate a club designed to serve as a forum for poets, artists, and musical performances. As a result, the club moved into the former building of the Golden Triangle, a speakeasy at 178 Seventh Avenue South. The Village Vanguard would go on to begin operations on February 22, 1935, dedicated to presenting patrons with poetry readings and folk music. Prominent visitors to the club during the 1930s and 1940s included poet Matthew Bondenheim, Caribbean calypso musician the Duke of Iron, and stand-up comedian Phil Leeds.

From the 1930s to the 1950s, as college students and artists began to take more interest in jazz music, the Village Vanguard’s focus began to shift towards featuring this music genre more prominently. Throughout the 30s and 40s, it soared in popularity among jazz clubs in NYC. The club served as a haven for small swing groups and received performances from Sidney Becht, Mary Lou Williams, and Roy Eldridge. By the 50s, the club had become one of the city’s leading venues for jazz music and worked to launch some of the era’s most celebrated careers. On November 3, 1957, tenor sax player Sonny Rollins would record three LPs during some of the club’s first recording sessions. A few years later in 1961, John Coltrane and Bill Evans would record Vanguard titles with Coltrane’s consisting of 22 songs produced in just four days.

The club remains most well-known today for its Jazz Orchestra which began as the Thad Jones-Mel Lewis Orchestra. After receiving rave reviews for three Monday night performances in February of 1966, the Orchestra has gone on to perform every Monday night since. In 1989 following the death of Max Gordon, his wife, Lorraine took over, running the establishment until June 9, 2018, when she died at the age of 95 from a stroke.

Open from 1938 to 1948, Café Society was one of the most popular jazz clubs in NYC. It was located on Sheridan Square in Greenwich Village. The club was founded by Barney Josephson, a shoe salesman from Trenton, New Jersey, who modeled the establishment after political cabinets he had visited in Berlin and Prague. Josephine devoted the club to showcasing American music, which in his opinion he viewed as being the blues and jazz—art forms created by Black Americans. At a time in which Black Americans remained on the margins of America, Café Society became one of the few nightclubs in which Black and white patrons could sit together in the audience, both being treated with the same modicum of dignity and respect.

Along this vein, the club’s name was suggested by Clare Booth Luce to satirize the usage of “café society” as a term that represented members of the moneyed crowd, with Josephson’s club having been created to defy the pretensions of the rich. Josephson would go on to trademark the name which had previously been coined by the society columnist Maury Paul who wrote as “Cholly Knickerbocker” for the New York Journal American. Alongside the club’s name, Josephine also adopted the slogan “The wrong place for the Right people,” with the capital ‘R’ signifying the club’s leftist leanings.

Despite the club being fully integrated, most of its clientele ended up being white as the Great Depression prohibited most New Yorkers, especially those of the working class, from being able to afford the entrance fee, despite being reasonably priced for the time. Even so, over its ten-year run, Café Society held performances from many of the country’s greatest black musicians. One such musician was Billie Holiday whose first live performance of the song “Strange Fruit,” which sold more than a million copies after its release, took place on the club’s stage. At the insistence of Josephson, Holiday closed her set with the song and then proceeded to immediately leave the stage, allowing for the audience to fully digest the weighted meaning behind its lyrics. Holiday would go on to perform at the club for most of 1939, an endeavor that helped to build her onstage confidence and refine her act. Café Society also helped to launch the careers of Ruth Brown, Lena Horne, dancer Pearl Primus, and Big Joe Turner and popularized gospel groups like the Dixie Hummingbirds and Golden Gate Quartet.

Unfortunately, though the club was able to book well-known performers, profits were still not high enough to keep the business afloat. As a means of saving it, a second branch of the club was opened on 58th Street between Lexington and Park Avenue, coming to be known as Café Society Uptown, while the original location was Café Society Downtown. Unlike its downtown counterpart, Café Society Uptown sought to attract a more affluent clientele, which ranged from prominent Black artists and intellectuals such as Sterling Brown and Langston Hughes, the world heavyweight boxing champion Joe Louis, and even Eleanor Roosevelt.

In 1947, Josephson’s brother, Leon, a well-known communist, and attorney for both locations of the club, was subpoenaed by House Un-American Activities Committee for his political beliefs. As he refused to answer the committee’s questions he was charged and convicted of contempt of Congress and began a one-year jail sentence in March of the following year. Following this decision, both Leon and Barney were attacked by the press, leading to the clubs’ revenue dropping 45% in three weeks. After the club’s losses reached more than $900,000 Josephson sold the club on March 2, 1949. Though Café Society may have reached its end, Josephson went on to open a restaurant called the Cookery in the 1960s. After adding in a piano at the request of Mary Lou Williams, Josephson returned to his roots and began booking live music performances. Beginning in 1977, Alberta Hunter performed at the restaurant until her death in 1982. Just two years later, the Cookery was closed. After he passed away on September 29, 1989, a memorial concert was held in November at St. Peter’s Lutheran Church in his honor.

On December 15, 1949, the jazz club Birdland joined the New York music scene at a time in which the city served as one of the country’s top locations for jazz performances. Irving Levy, Morris Levy, and Oscar Goodstein—along with six other partners—purchased 1678 Broadway, located just north of West 52nd Street from Joseph “Joe the Wop” Catalano to house Birdland. The venue sat around 500 people, with ample bandstand space for performers and a long bar, tables, booths, and folding chairs for customer usage. Priced at just $1.50, Birdland was frequented by an impressive 1,400,000 persons during its first five years, making it one of the top jazz clubs in NYC seemingly overnight.

The club’s name was specifically chosen to capitalize on the profile of jazz saxophonist Charlie Parker—more commonly known by his fans and fellow musicians as Bird, a contraction of his formal nickname Yardbird—who served as its first headliner. Over the club’s initial fifteen-year run, it relied on a business model which consisted of double and triple bills which commenced at 9 p.m. and ran sometimes until dawn. Many well-known jazz musicians frequented the establishment including John Coltrane’s Quartet and DJ Symphony Sid Torin, who broadcasted live from the club to audiences up and down the eastern seaboard. Similarly, Birdland was also visited by many of the time period’s most well-known celebrities including Marilyn Monroe, Frank Sinatra, and Sugar Ray Robinson.

At the same time, Birdland became a site of violence, with trumpet player Miles Davis being beaten by a New York City policeman on the sidewalk in front of the club. Irving Levy was also stabbed to death inside the club while trombonist Urbie Green was performing. His body was later found near the service area. By the 1960s, with the emergence of Rock and Roll, jazz clubs in NYC began to lose their popularity and Birdland’s finances began to decline. It eventually closed to the public in 1965.

However, Birdland’s legacy does not end there, with the club eventually reopening in 1985 at 2745 Broadway on 105th Street. The club quickly regained its notoriety and hosted more than 2,000 emerging artists during its first 10 years back in business. Owner John R. Valenti felt that the spirit of the club’s original midtown location had been lost, however, and as a result in 1996 he moved it to West 44th Street where it remains today. Recent performers at Birdland have included Diana Krall, Dave Holland, Regina Carter, and the last concert of Toshiko Akiyoshi’s jazz orchestra, which took place on December 29, 2003. Even as Birdland has come and gone, the club has remained a staple reference in American pop culture. Visited often by many writers of the Beat Generation, Birdland was mentioned in Jack Kerouac’s novel On The Road. The club has been featured in a number of songs such as Us3’s single “Cantaloop,” Weather Report’s hit “Birdland,” and U2’s “Angel of Harlem.” A version of Birdland also exists on the children’s television show Sesame Street, being run by Hoots the Owl.

Sweet Basil’s originally opened in 1974 at 88 Seventh Avenue South as a health food restaurant. The jazz came a bit later. By the 1980s, it was one of the most popular jazz clubs in NYC. It became a destination where artists like Gil Evans, David Murray, Cecil Taylor, Ron Carter, and more recorded live albums.

Sweet Basil’s closed in 2001 and was briefly revived as Sweet Rythm. Though Sweet Rhythm lasted until 2009, it never earned the same notoriety as Sweet Basil’s.

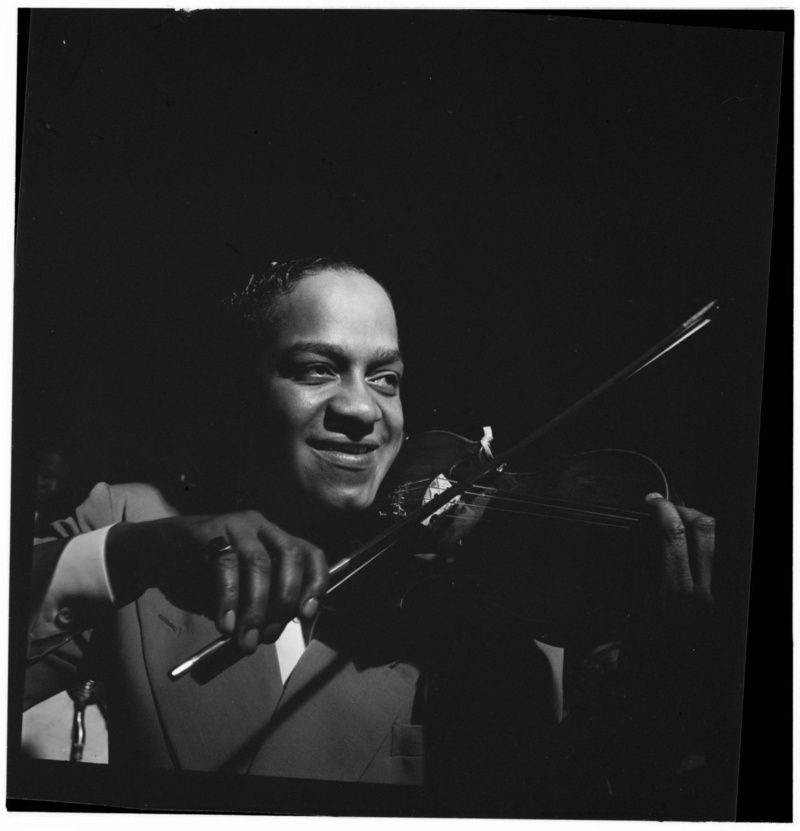

Smalls Jazz Club is a relatively new jazz club, founded in 1994 by former Navy submariner and jazz violinist Mitchell Borden. In the early days of Smalls, visitors paid just $10 for admission. The basement-level club had no liquor license, so guests could bring their own drinks to sip on as they sat for as long as they chose, listening to musicians curated and booked by Borden himself.

In 2002, the club went bankrupt, and Borden focused his energy on a new venture, Fat Cat, a bar for college students. Small’s was purchased and temporarily turned into The Rio Bar. By 2004, jazz was back at Smalls. Soon jazz pianist Spike Wilner and his friend Lee Kostrinsky became partners with Borden in the renewed Small’s venture. Through the Pandemic. the club survived thanks to support from the SmallsLIVE Foundation, a not-for-profit arts organization. In 2014, Wilner opened a second club on the opposite corner of West 10th Street and 7th Ave – Mezzrow. It is “dedicated to “Really The Blues” Mezz Mezzrow and draws its inspiration from the great piano rooms of the New York past, particularly Bradley’s.” You can check out upcoming performances for Small’s and Mezzrow here!

Blue Note in Greenwich Village was founded in 1981 by Danny Bensusan. While he struggled to turn a profit in the first few years in business, but was soon attracting legends like Sarah Vaughn, Lionel Hampton, Dizzy Gillespie, Stanley Turrentine, Oscar Peterson, Ray Brown, and Tito Puente. By 1988, Blue Note began to open more locations internationally. The first overseas Blue Note location was in Tokyo. Today, there are locations in Italy, Brazil, and China.

In 2011, Blue Note introduced its own music festival that features “jazz, soul, hip-hop, R&B, and funk players, trailblazers, and influencers.” The month-long festival, which takes place in June, is hosted at a variety of different venues across the city. The headliners for 2023 include Grace Jones., Bruce Hornsby & The Noisemakers with special guests John Scofield, Kenny Garrett and Christian McBride and Chucho Valdés, and Paquito D’Rivera.

Hailed as “the best jazz club in the world” by pianist Harold Mabern, Smoke Jazz Club located at 106th Street and Duke Ellington Boulevard was originally Augie’s Jazz Bar. Augie’s opened in the 1960s and closed in 1998. Former employee Paul Stache and his business partner at the time Frank Christopher took over the lease. They changed the name to Smoke, after the eponymous movie written by the writer Paul Auster, a regular at the club. In the movie, the character played by Harvey Keitel was largely based on Augie’s owner, Augusto “Gus” Cuartas, Stache told Gothamist.

Smoke opened in 1999 and soon became a world-renowned jazz. institution. The club was closed for two years during the pandemic and the owners used that time to make some major renovations. Smoke reopened in June 2022.

Next, check out The Queens Jazz Trail and Vintage Photos of the Cotton Club

Subscribe to our newsletter