Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

If there is proof that history repeats itself, look no further than the town of Flemington, New Jersey. Added to the 2016 List of 11 Most Endangered Historic Places in the United States by the National Trust for Historic Preservation, Flemington is a warning story for small historic towns across America. Located an hour and a half to two hours southeast from Manhattan Flemington was once the epicenter of the most famous trial of the century – the trial of the kidnapper and murderer of Charles Lindbergh’s baby, Bruno Richard Hauptmann.

Flemington’s quaint Main Street is lined with architecturally distinguished buildings, all part of the Flemington Historic District, a National Historic District added to the register in 1980. In fact, it is thought to be the second largest historic district in New Jersey, with about 80% of the buildings characterized as historic. It is particularly striking for its collection of buildings from different time periods, which the Historic Preservation Commission of Flemington contends has “architectural gems from every major historical period.”

But as we have seen in countless places around the country, a National Historic District designation has no legal bearing on the survival or preservation of historic architecture, and Flemington is now at risk of losing some of its most distinguished buildings.

“Poverty breeds preservation,” says Chris Pickell of Pickell Architecture, a firm whose offices are located in a Victorian house on Main Street. What he means is that the survival of such a picturesque Main Street in Flemington is the natural consequence of the town’s decline in the 20th century, following a boom in 1800s. The borough of Flemington was originally fueled economically by agricultural activity, particularly in fruits, and in glass manufacturing. Businessmen would stay overnight since it took so long to get there, creating business for the hotel and other proprietors. But like many other small manufacturing hubs in the country, the closing and relocation of industry led to a contraction of the historical town center, further enabled by suburbanization and the development of the highway.

At one point, Flemington served as a de facto off shore tax haven in the 1930s and 40s and was the address for around 140 major corporations. Then the state of Delaware offered even better incentives through its friendly corporate and tax law structure and the businesses made a swift exodus.

Pickell has been renovating many of the structures along Main Street, keeping the historical elements intact and in some cases, revealing original details that were lost along the way. New businesses have arrived and taken root along Main Street and foot traffic is up. But now, Flemington is entering a new moment. Its residents are hoping for a full revitalization – “It’s time,” seems to be the resounding call.

Yet, it seems that the learnings of the last fifty years since the early preservation laws were passed have not quite reached the town. History and architectural preservation can become an asset and economic driver, as towns like Kingston in the Hudson Valley and Setauket on Long Island (buoyed by its Revolutionary War spy ring history), have discovered. And preservation must be more than skin deep.

Redevelopment Plan for Main Street Flemington, which includes a rebuilding of the Union Hotel facade following demolition

In Flemington, the town has entered into a memorandum of understanding with developer Jack Cust Jr., who hopes to create a large mixed use project up to eight stories tall that would require the demolition of numerous historical buildings along Main Street. The developer claims that this plan is in line with the goals of the Hunterdon County Comprehensive Economic Development Study, but not only is it clearly out of context with the existing built environment, it would also subvert the town’s zoning and a 2014 Downtown Strategic Plan Report, commissioned by the Flemington Business Improvement District.

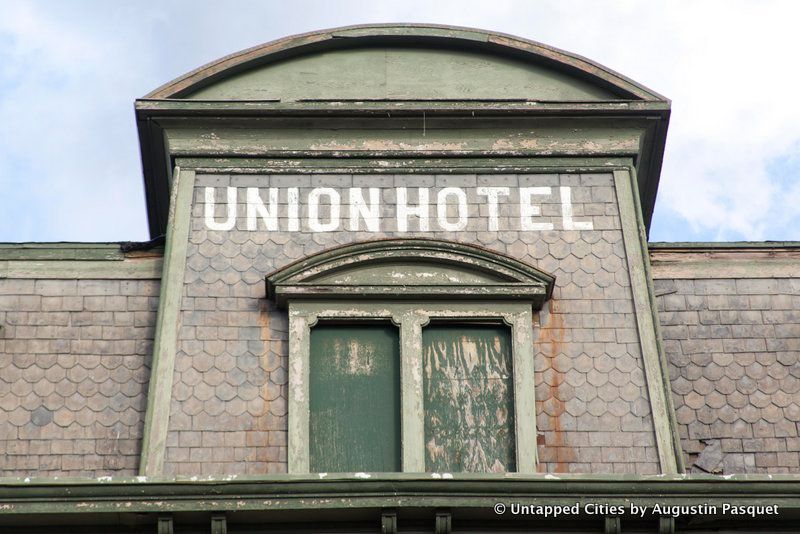

The 2014 strategic plan was a comprehensive and ambitious one – it sought to protect existing neighborhoods and building stock, while also amending zoning laws to enhance the commercial sector, encourage business and arts, and turn Flemington into a regional destination. Historical preservation was seen as one of the assets of Flemington and one of the main priorities was to reopen the Union Hotel, a stunning structure considered to be one of last examples of a small town hotel in the state.

The brick building has a two story wooden porch and a slate mansard roof. The southern half of the hotel was built in 1877, on the site of a stage coach stop that ran between New York City and Philadelphia. This portion replaced a three-story wooden hotel that had stood here since 1814. It was luxuriously appointed, with heated rooms, indoor plumbing and gas lighting. The second half of the hotel was built in 1878 and if you look closely, you can see the seam on the facade between the two sections.

The Union Hotel was built from virgin timber moved by barge from the Upper Delaware River watershed. It was also notable for Depression-era murals by two local artists, including the award-winning illustrator of the children’s books Bambi and The Jungle Book. The backside of the hotel has a wooden extension, which is in very poor shape (below).

Architectural details on the side of the hotel

The jury of the Lindbergh trial stayed in the roof of the Union Hotel and the journalists stayed in the hotel. For a brief period of time during the trial, Flemington was the headquarters of the global media. The restaurant in the hotel’s first floor closed in 2008 and the hotel had not rented guest rooms since the 1970s. For a period of time, a restaurant operated on the ground floor but a regulation that prevents the issuing of liquor licenses in downtown Flemington has deterred chances for its rental.

The development plans under consideration currently would see the demolition of the Union Hotel and replaced it with a facade recreation, surrounded by the style of mundane, placeless architecture seen in many suburbs around the country seeking to densify. The very ambitious plan hopes to attract a two or four year college, 50,000 square feet of retail anchored by local company Flemington Furs, a 103 room hotel, a medical facility, new restaurants, 230-250 units of housing, and 900 parking spaces, which would sit in a podium and in a garage, wrapped by apartments.

78 Main Street, one of the buildings that will be demolished with the redevelopment plan

In addition, three other historical buildings would be demolished in the same stretch of Main Street including 78 Main Street, an 1880s brick building, originally a dry goods department store, and 90-100 Main Street, the Hunterdon County National Bank, a large Italianiate structure modeled after the Ford Theatre in Washington, D.C. The safety deposit vaults inside still remain, as well as numerous original details on the exterior. The Borough of Flemington is currently being sued in two separated cases related to the redevelopment project and a petition to save the Union Hotel has been started.

90 -100 Main Street, another one of the buildings that will be demolished with the redevelopment plan

Using the urban planning guidebook Parking Generation, 3rd Edition, from the Institute of Transportation Engineers, we estimate that the number of parking spaces in the plan will more than suffice if shared parking spaces are not allowed, which is a conventional zoning method of calculation. Given that there will be varying temporal peaks in demand, due to the nature of the business activity, there will be hundreds of empty spaces during lower demand periods.

For example, on a Saturday peak demand period we calculate the need as follows. Residential: 306 spaces, Hotel: 94 spaces, Retail: 173 spaces, Restaurant: 173 spaces, Medical Offices: 0-15 spaces. Total: approximately 575-590 spaces. Weekday and Saturday night overnight demand would be even lower, at about 400 spaces, which is less than half of the capacity planned. Weekday midday peak demand would be about 700 spaces. In addition, our calculations are based on a reasonable occupancy of the businesses in the plan, which assumes that Flemington will be able to attract the residents and visitors the plan suggests.

Courthouse

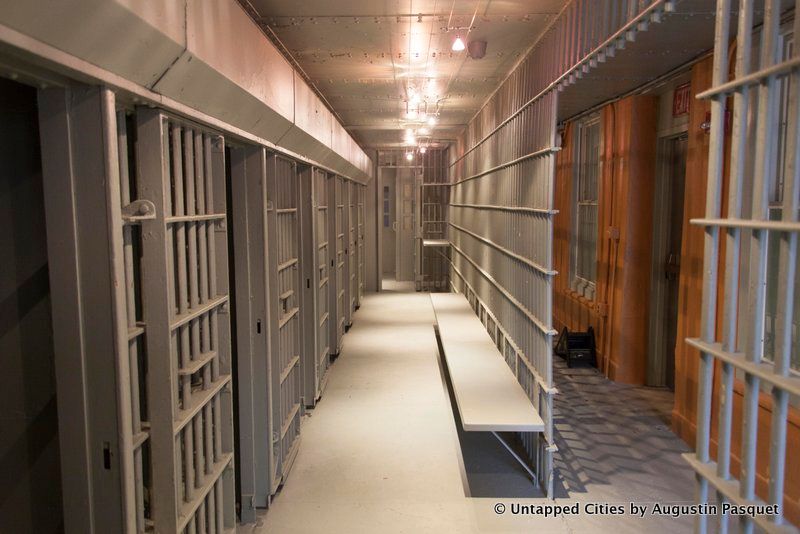

One building that will remain in the plan is the 1828 courthouse and jail, just across the street from the Union Hotel. The courtroom can still legally hold trials but is mostly used for ceremonial and public events, including an annual re-enactment of the Lindbergh trial. Its interior was restored to its 1935 state by Hunterdon County about ten years ago, showcasing original wooden pews, jury chairs, the original fireplace which heated the room and a 48 star flag. Portraits of figures associated with the trial hang in the room.

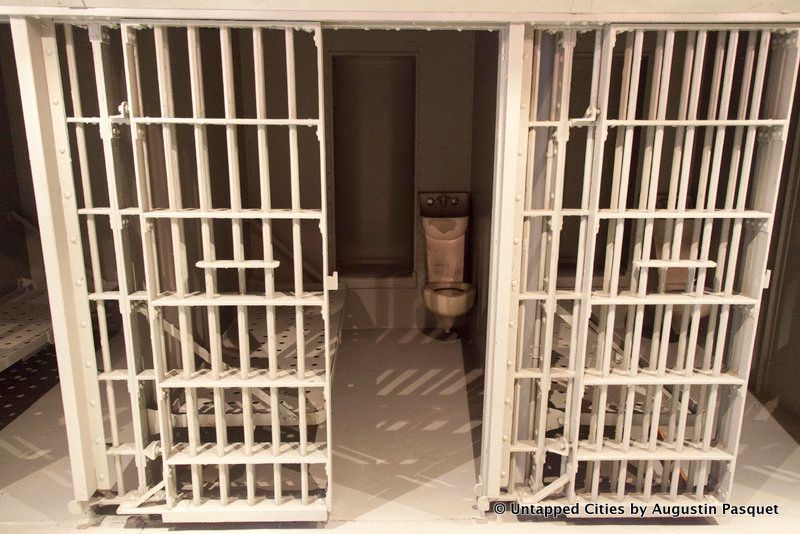

The original jail for the town was underneath this courtroom but in 1926, a new jail was built next door – a rather pioneering example of prefabricated construction. All the pieces for the jail were pre-made by the St. Louis Jail Building Company, moved to Flemington and put together on site. The sliding door locking devices for the jail were made by the Pauly Jail Building Company, a firm that still exists. It was in these cells that Bruno Hauptmann was held.

On a visit to Flemington, which we highly recommend before any demolition commences, take a walk north along Main Street from the courthouse. Along the road in front of the courthouse, you’ll find marker denoting the true meridian and a horse fountain along the road from 1902. On the interior side, it served as a water fountain for humans, on the exterior for horses and dogs.

Then one of the most adorable buildings is within view, the Samuel Southard Law Office from 1811. The Greek Revival building, designed by Mahlon Fischer, has a Doric style colonnade.

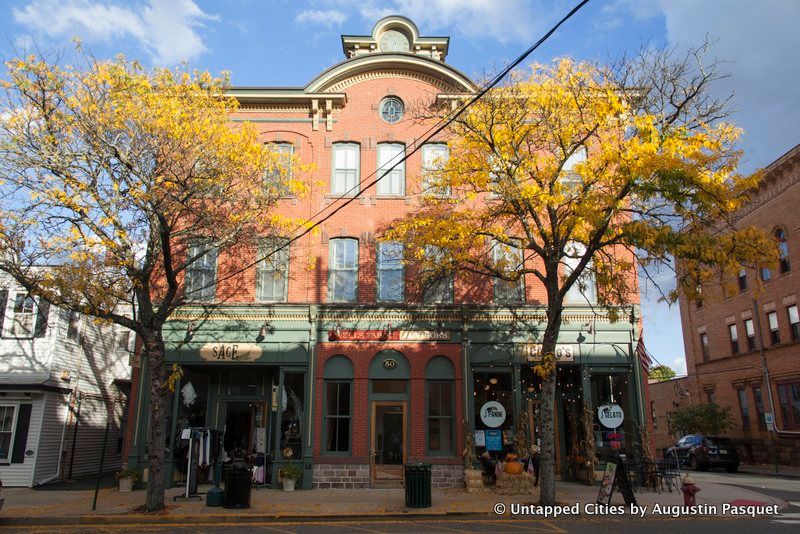

Across the street is the Town Clock/Rea Building from 1874, which was restored by Pickell and is now home to a clothing boutique and a cafe on the ground floor. Pickell discovered the original tin ceiling and other details in the restoration of this structure, built by clockmaker George Rea. The original clock mechanism still exists in the tower, along with the shipping crate the clock came in, stamped with the date 1876. On the same side of the street is the Bank Building, another restoration work by Pickell.

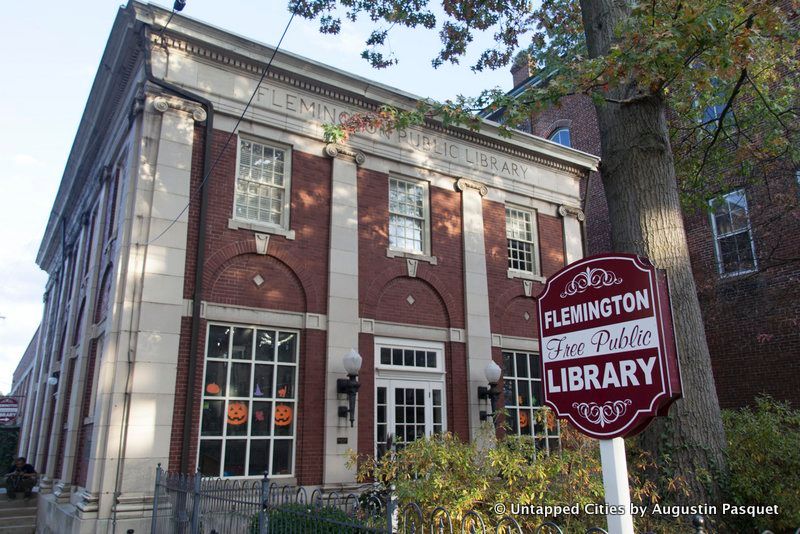

Crossing back to the other side of the street, the Reading/Large residence is a handsome work by Mahlon Fischer in 1847, with Corinthian columns and wide porch. It was restored recently by the Hunterdon County Chamber of Commerce, but lacks the the roof details it once had. Across from the Reading residence is the Flemington Public Library, built of brick and stone in 1910.

The Reading/Large residence

Flemington Public Library

There are many more beautiful buildings of a variety of architectural styles all along Main Street and on the side street. A visit to Flemington is a must, particularly as some of its historic architecture is at risk. Its residential buildings are a beautiful site to behold.

From a zoomed out perspective, one can easily see the potential of this town, with its rich architectural and social history. Every town has its Penn Station, the building that was lost that made its residents understand the necessity of preservation – perhaps the Union Hotel is Flemington’s. But the danger of wiping away such a large swatch of its town center could mean that the fundamental character of the town could disappear, limiting the potential of future preservation.

You can sign a petition to save the Union Hotel here. There are two pending lawsuits about the hotel redevelopment project, and you can read more about it here on the Historic Borough of Flemington website. Next, discover the historic town of Kingston, an easy weekend trip from NYC.

Subscribe to our newsletter