Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

The Rikers Island GreenHouse garden, run as a collaboration between The Horticulture Society and the NYC Department of Correction, provides an oasis of green on an island more known for its barbed wire and concrete

The following piece is based on the experience of Matthew DelSesto, a graduate student in urbanism at the Parsons School for Design.

For the past year, I’ve been an intern at the Horticultural Society of New York (The Hort), working for the GreenHouse program. GreenHouse is a jail-to-street program for sentenced inmates and detainees at Rikers Island Correction Facility in New York City. As a collaboration with the NYC Department of Correction and Department of Education, GreenHouse represents an innovative approach to prison programs that give inmates the opportunity to work in a garden, classroom and green house space.

While farming has historically been part of the operation of correctional facilities like Rikers Island (for more than 100 years), the GreenHouse program takes farming to the next level, integrating vocational training, environmental education and horticultural therapy. This creates an atmosphere for incarcerated men and women to begin building the skills, confidence, and motivation they may need as they are re-enter the community and the workforce. A key component of the GreenHouse program is the aftercare component, known as the GreenTeam, which provides transitional employment and further training.

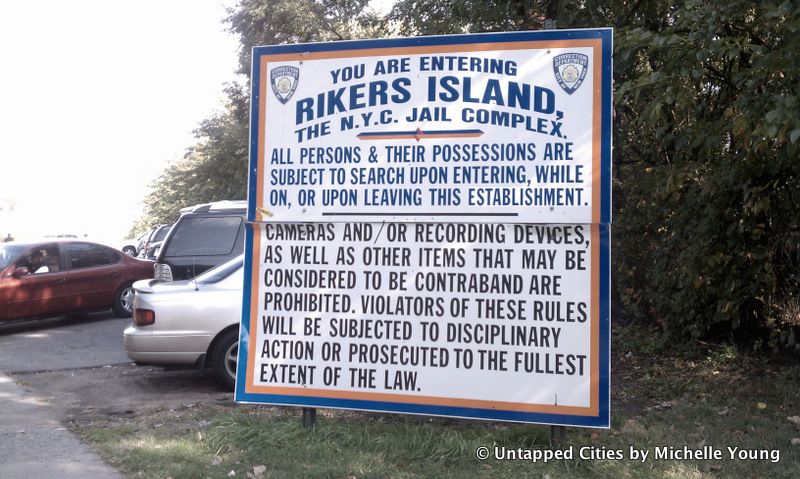

Rikers Island Correction Facility in New York City is the largest jail complex in the world, yet its impact on New Yorkers remains somewhat invisible, hidden from mainstream society. In spite of their invisibility, through the GreenTeam, formerly incarcerated men and women have made tangible impacts on the city’s built environment, beautifying hundreds of green spaces throughout the city in the last 15 years.

With these programs, The Hort is actively generating landscape architecture and green urbanism projects. This particular kind of landscape urbanism pushes us go beyond the aesthetics and forms of green design, leading us to critically engage in the complicated and challenging realities on the ground. Since its inception, the GreenHouse and GreenTeam were conceived as an evolving multi-layered design project that includes the design of social services and physical structures, adjusting to inmate experiences and skills over time. This more comprehensive approach to “green” design generates ripple effects that transform lives and grow beautiful spaces.

As a student interested in issues of vacant land and public space, I have noticed that outsiders tend to see “offenders” in the criminal justice system with the same suspicion as a parcel of “vacant” land—undeveloped, not worthy of respect, potentially dangerous. The men and women I meet on Rikers Island tell a different story—adults struggling to find some sense of normalcy in their lives, crimes in a context of chaos and crisis, young people with untold reservoirs of untapped potential. When we ignore these realities we exclude entire groups of people and spaces from our collective imagination of the future city, foreclosing possibilities before they have the chance to emerge, restraining people before they have the opportunity to work towards their potential.

While just about every GreenHouse student finds a healing power in nature and temporary relief from the stress of life on Rikers, program participants have gone on to gainful employment in the growing green jobs sector. And green is not just a color. It’s a call to transform the larger structures that shape our cities—creating vibrant green spaces and forging pathways to opportunity, cultivating new teams of gardeners in unlikely places and building the city of tomorrow.

Untapped Cities also previously went into Rikers Island to teach incarcerated juveniles with the Rikers Island Project. Read more about it here.

Subscribe to our newsletter