Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

There may be no topic hotter than affordable housing in New York City right now, with it being the centerpiece of Mayor DeBlasio’s OneNYC strategic plan. But the battles that will be waged to create and preserve the 200,000 units of affordable housing promised in the next decade – debates over design, inclusivity, exclusivity, displacement, and more – are hardly new. This is precisely the story that a new exhibit at the Museum of City of New York aims to tell in Affordable New York: A Housing Legacy, curated by architectural historian and author Thomas Mellins. As a wider goal, it aims to situate New York City as a pioneering force behind the affordable housing movement, in its various manifestations since the 19th century. In fact, New York City was the first city to pass comprehensive tenement house laws in 1877.

The sheer numbers of the affordable housing issue today are staggering: an estimated 1.2 million New Yorkers live in some type of subsidized affordable housing, equivalent to the number of people that live in the cities of Boston and Washington D.C. combined. That’s over 14% of the population of New York City. And New York City faces a particular challenge, due to a higher cost of living.

Affordable New York: A Housing Legacy has been more than a year and half in the making, expanding on an exhibit for the 75th Anniversary of the New York City Housing Authority that never came to be in 2009. As Mellins tells us in a walkthrough of the exhibit, “Not only did interest in the topic increase in the years preceding that, but since I started, it’s only exploded as a subject. You cannot open the newspaper or turn on the television or computer without confronting this.”

With affordable housing the hallmark cause of Mayor DeBlasio’s administration, the exhibit appropriately opens with the present-day situation, with accompanying tools and definitions to situate the topic in New York City. Mellins is careful to remind visitors however that the show “is not polemical or an advocacy show per se. What it does is look at the current moment and the future and say, We are standing on the shoulders of many, many people. That the problem of the scarcity of affordable housing or the efforts to address it are not new in New York. And in fact, New Yorkers have been doing this for a century and a half. So it’s really about that legacy.”

Apart from the sheer number of those in affordable housing units in New York City, the exhibit also emphasizes the range of people that are served by the various initiatives here. It’s important to remember, as Mellins says, these are “not the poorest of the poor, and in fact it might be surprising that someone who [makes quite a bit of] money is eligible, but New York is very expensive and it always has been.”

As such, a larger percentage of residents qualify for affordable housing compared to that in other cities, and because the government includes families making up to 250% of the Average Median Income (AMI) in subsidies, this means a household income of up to $142,395 for four in New York City could qualify. Still, of course, 78% of affordable housing in the city is for those at low income and below.

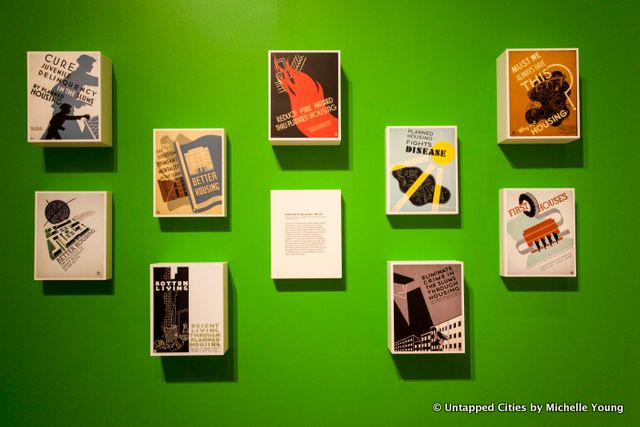

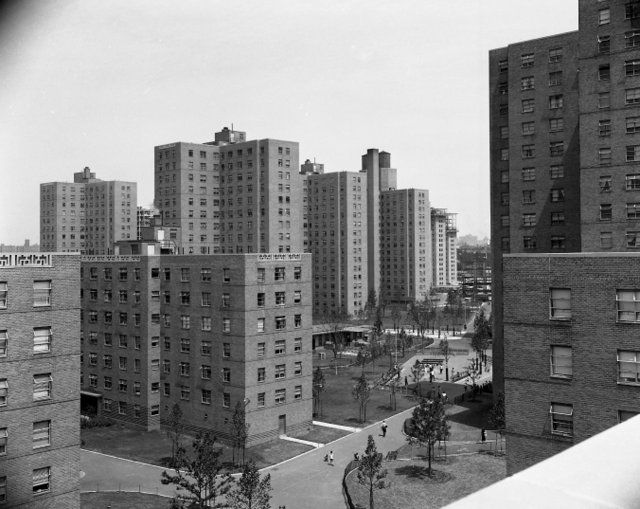

Another important aspect of Affordable New York: A Housing Legacy looks at design, that “it doesn’t all look the same,” says Mellins, “and that the paradigm that we have in our mind of the red brick towers on the superblock sites exist, and it exists in large number, but that’s only one type.” The entrance to the exhibit looks at this diversity of styles, with museum-commissioned photographs by Andrew Moore to showcase the range of affordable housing in New York City. These span from 19th century philanthropic tenements, to Lower East Side developments built by labor unions, the inescapable towers in the park ideal, places like Waterside on the East River from the 1970s, to picturesque prefabricated single family ranch homes in Charlotte Gardens, the Bronx, and inclusionary housing in Hunters Point South. Each photograph, Mellins says, “represents some kind of idea, or type or program that you then learn more about inside.”

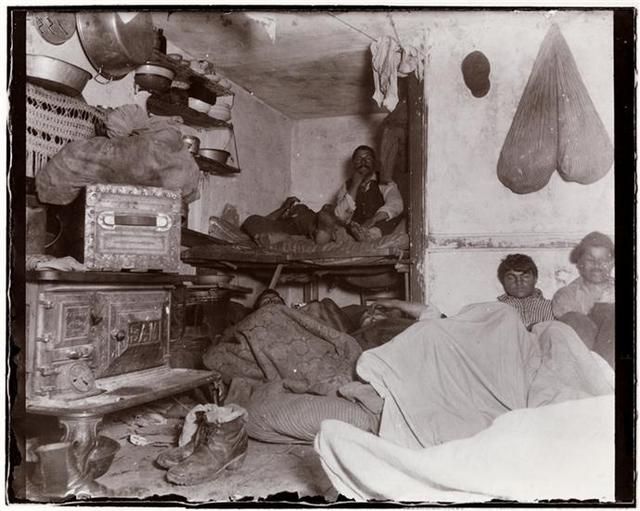

Lodgers in a Bayard Street tenement. Photo by Jacob A. Riis via Museum of the City of New York.

The main gallery is organized chronologically and shows a “historic sweep,” says Mellins. It begins with the first efforts, known as “philanthropic tenements” and “sanitary tenements” by private industrialists and situates the movement in the pioneering work of photographer Jacob A. Riis, the subject of another exhibition also currently at the Museum of the City of New York.” As Mellins contends, “Interestingly enough, the first government interventions into housing in New York don’t actually have to do with affordability, they have to do with conditions, and what motivates it are concerns about public health.”

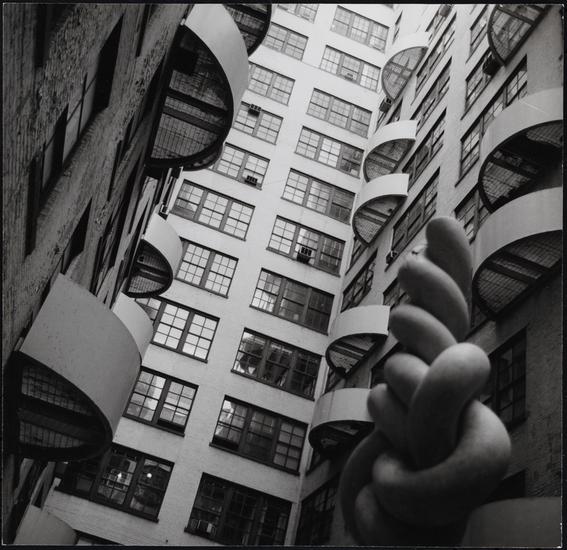

Tower Buildings Apartments (Cobble Hill Towers), Brooklyn. 1878. Photograph: Andrew Moore, 2015

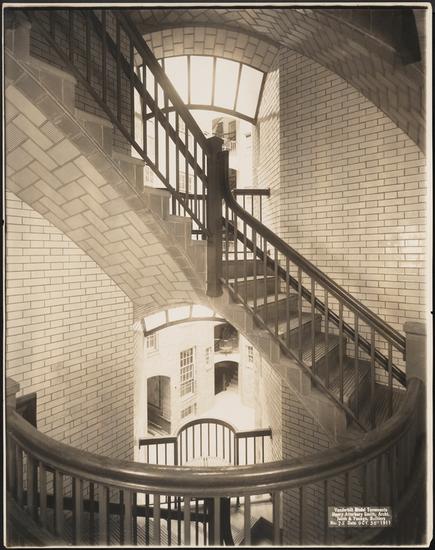

Staircase inside the Vanderbilt Model Tenements, 1911. Photo by Wurts Brothers from Museum of the City of New York Collections.

Even philanthropic tenements, which appeared as early as 1877, had an additional benefit: keeping workers healthy to maintain a steady labor supply for the city’s economy. And, the financial model ensured that the industrialists would still profit from such housing ventures, something Mellins feels is quintessentially New York: “You do the right thing, but you don’t lose your share. You make buck. That idealism married to pragmatism seems utterly New York.”

First Houses (Astor Housing project), Alphabet City, Manhattan. Completed: 1936. Photographer unknown/Courtesy of La Guardia and Wagner Archives, La Guardia Community College/The City University of New York/New York City Housing Authority )

In 1926, the government becomes officially involved in affordable housing when New York Governor Al Smith signs a bill that creates tax and finance incentives to build housing for the poor, formalizing activity spurred by the private sector. This move brings in the labor unions, which build places like the Amalgamated Houses in the Bronx, and provide a model, both architectural and financial, for this new type of housing.

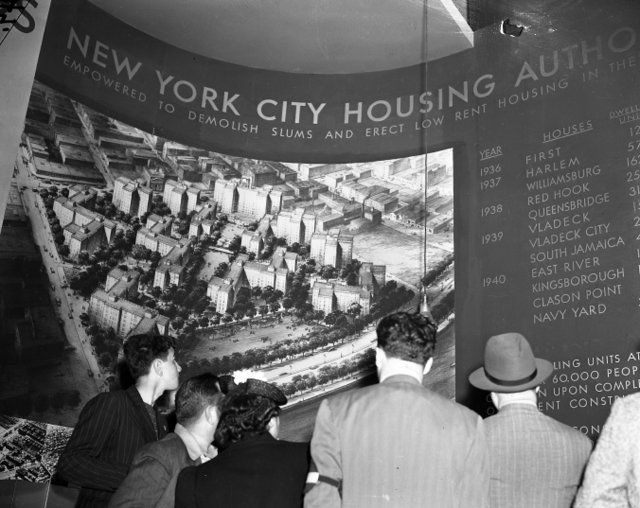

The NYCHA exhibit at the 1939-40 World’s Fair, June 8, 1940. La Guardia and Wagner Archives, La Guardia Community College/The City University of New York, courtesy of the New York City Housing Authority

The Great Depression also further highlights the need for government intervention, and New York City receives a disproportionate amount of New Deal dollars. In 1934, the country’s first housing authority, New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) is formed, whose vision incorporates both housing and social services. The exhibit also covers the various objections to public housing, which include its role in urban displacement, issues concerning racial segregation, and its believed affiliation with socialism and Communist ideals.

Wagner Houses, East Harlem, Manhattan. La Guardia and Wagner Archives, La Guardia Community College/The City University of New York, courtesy of the New York City Housing Authority

Affordable New York: A Housing Legacy also showcases the other types of non-public, affordable housing initiatives like Mitchell-Lama, Title 1 (associated with slum clearance and urban renewal), and efforts of private companies like MetLife, which built Stuyvesant Town, originally a racially segregated development. Mellins points out that though NYCHA adopts a non-discriminatory racial policy in its founding in 1934, racial discrimination does not become illegal in private rental housing in New York until 1957.

Aerial view of NYC with Stuyvesant Town superblock along the East River. Image via Museum of the City of New York

As the exhibition moves into the 1960s, the role of labor unions increase in the Post WWII period. Architectural critique begins to seep into the narrative and younger architects like Richard Meier and Phillip Johnson are hired to make their mark on affordable housing design. Newspaper excerpts show the commentary of architectural critics like Ada Luise Huxtable and Paul Goldberger on housing, even Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown write a treatise entitled “Co-Op City. Learning to Like It,” a direct play on their seminal work, Learning from Las Vegas.

Westbeth Center of the Arts. Image via Museum of the City of New York.

Along the lines of architecture, Mellins also includes Westbeth Center for the Arts in Greenwich Village as an early important example of adaptive reuse, as housing begins to be aimed at particular communities in New York City. Westbeth in turn had an influence on the popularity of loft living in the city, and Mellins believes this shows that “affordable housing can actually be an incubator of ideas that spread to everyone.”

Waterside Plaza, Kips Bay, Manhattan. Completed: 1973. Of the towers in the complex, those built after 1973 would become market rate. Photograph: Andrew Moore, 2015

In 1973, President Nixon establishes a moratorium on public housing nationwide which limits large-scale new housing. As a result, NYCHA has built very few new buildings since this time period and government involvement has become focused on incentives. Beyond the photographs of visual decay and grit that so often resurface about the 1970s, Mellins wants to emphasize what the current, contrasting economic situation offers to New York. He says, “You walk down the street now and for better or for worse, there’s construction everywhere. There are 90-story buildings going up. You may hate them, but the reality is a lot of money is being invested in New York.” In the 1970s, there was massive disinvestment in New York, to a scale that is difficult to comprehend today.

Architectural Model of Via Verde in the South Bronx

The exhibit ends with questions about the future of NYCHA properties and a showcase of new paradigms in affordable housing, including Via Verde, a skyscraper/townhouse combination in the Bronx with stepped terrace gardens. The building that has already contributed to the revitalization of the Melrose neighborhood and has encouraged the influx of new amenities. Indeed, just today, The Wall Street Journal proclaimed that Melrose is the “next dining destination” with the opening of two restaurants by James Beard-winning chef Douglas Rodriguez.

Model of Domino Sugar factory redevelopment by Two Trees, designed by SHoP Architects

Though these new paradigms do not yet include the upcoming co-living initiatives by startup darlings like WeWork and General Assembly, or the already open Crown Heights building Common, the initiatives in the current landscape, particularly by private players, showcase both the demand for affordable housing today and the entrepreneurial spirit that has characterized the legacy of the housing movement since its inception in New York during the 19th century.

Check out Affordable Housing: A New York Legacy at the Museum of the City of New York as well as the exhibit Jacob Riis: Revealing New York’s Other Half. Also see 10 of our favorite highlights of the Affordable Housing exhibition. Get in touch with the author @untappedmich.

Subscribe to our newsletter