Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

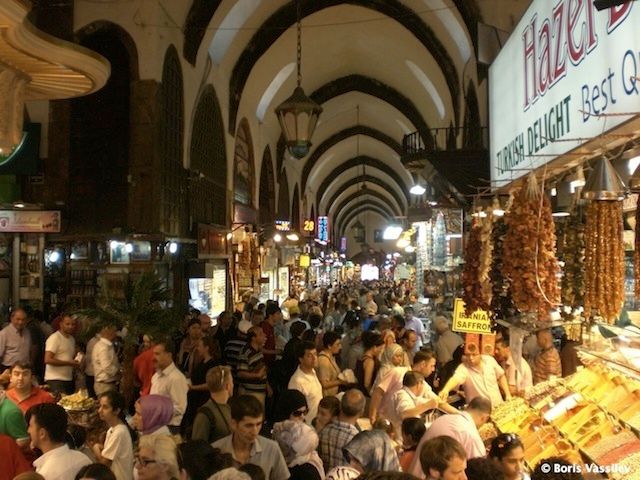

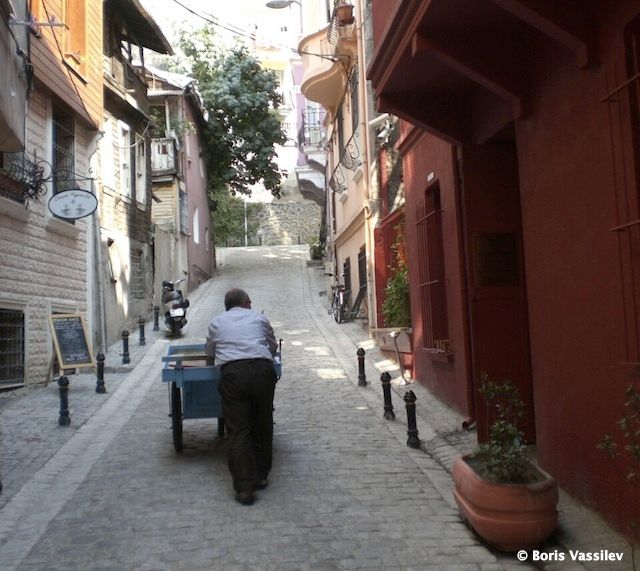

Istanbul’s rooftops are the baked red clay half-pipes that cup into one another, which you can find anywhere in Europe; in contrast to this, the facades of entire building blocks are accentuated by ornate geometric and floral tilings – Eastern Europe fitting up against a traditionally Islamic, Middle Eastern sentiment. It is hard to think of any part of Istanbul as a relic of another time because the entire city is happening and changing in the moment, most immediately in the famous Covered Bazaar (or Grand Bazaar), a half-millennium old construction housing the most premium ateliers and shops, and the labyrinthine network of stands that grows radially out from it.

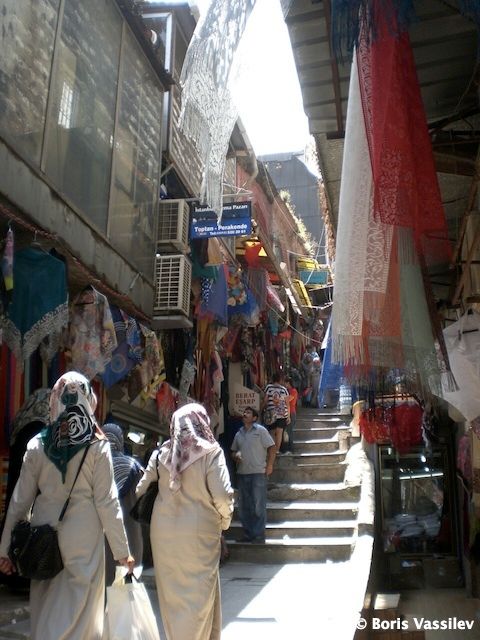

In this center of Istanbul, and in the city as a whole, ticks a carefully crafted mechanism of commerce. Every interaction between travelers is a transaction. It seems appropriate to say “travelers” because it is hard to imagine anyone knowing the exploded expanse of the markets intimately enough to call it a familiar home. In a very different way, the inviting nature of the bright stalls, the enticing duck-behind diukians becomes quickly familiar, not because of any direct interest in bartering, but because of the very human aspect underlying this life. Everything sold is directly useful to some degree, especially in the markets immediately outside of the old city, where the rows of hookahs, ranging from teaspoon to toddler-sized, are replaced by boxes of pipes and bathroom fixtures of startling variety, condition, and age, boxes of socks (“Chift chorapi!”), and the ever-present water bottle peddlers, the lifeblood of the city. Everyone is seeking to purchase something, and the entirety of social interaction runs around it.

It is curious to see how any goods that are labeled as authentically Turkish – ornate sheet metal lamps, fine clothes and assaulting spices – are commodified, packaged and sold as eagerly as possible to visitors, a deep contrast to the juxtaposed markets outside of the tourist range, which sell ubiquitously comfortable Western brand names and goods to the authentically Turkish people. Tourists walk out of the covered market with a 15th century art print of a dervish, and Istanbulites walk out of an air-conditioned mall touting a Whirlpool. In order for Turkey to complete the transaction of entering the European Union, its own cultural tradition seems to have to be reduced to only skin deep.

Passersby are addressed in half a dozen languages if their eyes so much as stray over the goods in the shops (“Merhaba, Hello, Guten Morgen, Dobri den” and the always effective “Good price!”), locals loudly exclaim their disapproval of listed prices and are consoled with exultations and warnings that they are putting the seller’s family out on the street if he takes the price they are asking, one he takes anyway. Travelers who wish to avoid these scenes keep a dead look ahead, or sneak looks under large sunglasses. But these visual transactions permeate far deeper, into the core of cultural interaction. Looking into the eyes of your fellow market-goer, a common catch in the Western world where strangers often make eye contact to confirm one another’s movement, or to share a small humor over something they’ve both seen, takes on a more guarded form in these corridors of exchange.

More often than not, looking up to see the eyes of another person, especially someone of the opposite sex, is greeted by their gaze fleeting away. It’s as if the very act of looking at someone invites an interaction, but unlike the one in the shops, this one is not greeted with enthusiasm. It is particularly striking in the lower markets, where most of the barterers are women, and many of them are wearing burkas, with their eyes as one of the only direct human links, now diverted. This creates a sense of isolation, even among the throngs of merchants and soon-to-be owners of pashmina, tea, and evil-eye charms that they did not even know they needed, and simultaneously allows travelers to find the goods they want to purchase without distraction, and to intensify their own feeling of alienation in this crossover marketplace.

There was no other choice of location for Orhan Pamuk to craft his Museum of Innocence, the psychotically meticulous and fascinating house containing exhibits corresponding to each chapter of his book of the same name, a story about a complex affection set in 1970s Istanbul. The museum itself is a study in obsession, with every exhibit a memorial to a particular memory that the narrator has of his object of desire, later wife, beginning to great effect with a display case of thousands upon thousands of labeled and cataloged cigarette butts. One has to imagine that Pamuk had a battalion of lipstick-clad assistants whose sole purpose it was to smoke and perfectly crumple the spent cylinders so that he could pin and tag them, butterfly-like. Other display cases are filled with a trinket collector’s dream, a decade’s worth of thrift purchases by Pamuk as he accrued the items necessary to complete the experience in his mind. Walking through the museum is to understand what it is like to take the most private thoughts and obsessions of a person and catalog them in a way for a public eager to peek in, without questioning the potential loss of earnestness in such a drastic reversal.

Photography is not allowed inside the Museum of Innocence, all transactions must be complete at the door. The guards look you in the eyes here, especially when you are obviously lying about the validity of your student card, and it only serves to remind you that you are in between the outside and the inside, of the museum, of the market, of Istanbul, a traveler in a state of transit and transaction.

The Museum of Innocence / Masumiyet MàÆ’ ¼zesi

Firuzaà”žà… ¸a Mh., àÆ’” ¡ukur Cuma Cd 24, 34424 Istanbul, Turkey [map]

+90 212 252 9738

Grand Bazaar

Kayà”ž ±à”¦à… ¸daà”žà… ¸à”ž ± Mh., Hilal Sk 29, 34755 Atasehir à”ž °stanbul, Turkey [map]

+90 535 220 1472

Follow the author on Tumblr. Read about what’s happening to Istanbul’s historical neighborhoods in the city’s push to become a global city.

Subscribe to our newsletter